What set Northern Ireland's Troubles alight?

Hulton Archive/GETTY IMAGES

Hulton Archive/GETTY IMAGESAt least a year before August 1969, community tensions across Northern Ireland had been heating up, with civil rights marches and campaigns of civil disobedience.

There had been violent clashes involving nationalists, unionists and the police.

Then, a highly contentious Apprentice Boys parade was given the go-ahead in Londonderry on 12 August.

This was the spark that lit the flame that became the Battle of the Bogside.

Nationalist protestors threw stones and bottles at the loyalist parade as it passed close to a Catholic area; Protestant supporters responded in kind.

Royal Ulster Constabulary officers (RUC) moved in and became involved in a pitched battle with nationalist rioters around the nearby Rossville flats.

Watford/Mirrorpix/getty images

Watford/Mirrorpix/getty imagesDerry and Strabane Councillor Eamonn McCann was a leading civil rights activist at that time and he vividly recalls the events.

"This wasn't a gun battle which people were spectating at and it wasn't a gang of hooligans, or the young people of the area out rioting against the police," he said.

"This was the entire community of the Bogside erupting onto the streets."

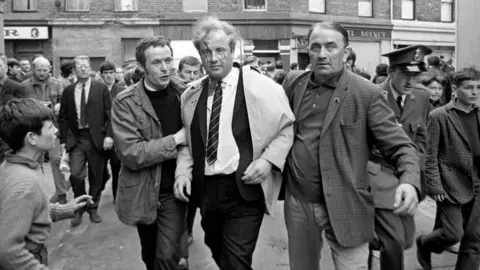

Peter Ferraz/getty images

Peter Ferraz/getty imagesRetired school teacher Terry Wright was one of the Apprentice Boys on parade that day.

He had been involved in the early civil rights movement, but became disillusioned with the campaign when some leaders started calling for the "smashing of the British state".

Reflecting 50 years later, he said the Apprentice Boys were not the only ones who thought the parade should go ahead.

"John Hume and other civil rights leaders were appealing for the march to be allowed to proceed peacefully.

"They, as civil rights campaigners, were claiming the right to march and they were arguing that that should be afforded to others."

The rioting in Derry continued until 14 August, attracting worldwide media attention.

PA Media

PA MediaWithin a few days, the trouble had spread to Belfast, particularly along the Shankill and Falls interface.

A Protestant mob attacked and set fire to more than 40 Catholic homes in Bombay Street in the Clonard area.

The Canavan family were among those whose house was destroyed - sisters Jean and Patsy still live in the rebuilt street to this day.

Jean McAnoy remembers returning to Bombay Street the following day with the rest of her family.

"As we were walking down the road, my mummy turned to our next door neighbour and said: 'Don't worry, it'll only be windows we'll have to put in'.

"But when we turned the corner into our street and we saw the houses, there was nothing left.

"They were all burnt and we were just standing there in what we went out in."

The events of August 1969 radicalised a generation.

Prominent republican and former IRA prisoner Sean "Spike" Murray told BBC News NI: "A couple of weeks earlier we'd been watching people landing on the moon. That night we were watching families homes being burnt and people getting shot on the street.

"What do you do if the police refuse to come out to defend your area, what do you do if your neighbours are burnt out of their house?

"What do you do if your 15-year-old friend is shot dead in the midst of that?

"That was the stark choice people had to make and people in their mid teens shouldn't have to make those choices.

"One of my priorities is to ensure that choice is not presented to another generation."

Independent News and Media/GETTY IMAGES

Independent News and Media/GETTY IMAGESMany young Protestants on the other side of the interface were asking themselves similar questions, among them Shankill loyalist Stephen "Issac" Andrews.

"An uncle of mine was shot coming out of his work in Mackies," he said.

"He was brought into the house and his white shirt, which he always wore to work, was plastered in blood.

"As a young fella seeing that, to be totally blunt and honest with you, I just wanted to go out there and get involved in something.

"This was coming directly to my family and my thinking was that I need to be doing something about that."

'They're coming to burn us out'

Protestants were also forced out of mainly nationalist areas in sectarian violence.

As a 14-year-old schoolboy living in a street close to the interface at that time, Sam McCrory remembers the fear felt in unionist households.

"Prior to Bombay Street, there were Protestant families burnt out below Townsend Street and behind Hastings Street police station," he said.

"I'll never forget the noise of the hordes gathering and my dad telling me that they were coming in, they were coming in to burn us out.

"That will live with me until the day I die."

Peter Ferraz/GETTY IMAGES

Peter Ferraz/GETTY IMAGESAccording to Dr Eamon Phoenix, the events of August 1969 would prove pivotal in the history of the island of Ireland.

"For the first time, people were talking about being able to cut the atmosphere in Northern Ireland with a knife," said the historian.

"We had all the modernisation of a first-class national health service and education system, but there had been no modernisation at a political or governmental level.

"Somehow politicians and people were still living in the permafrost of a political stone age."

'Total polarisation'

The summer of 1969 brought an end to many things, including Catholics and Protestants living side by side, said Dr Phoenix.

"After August 1969, there was total polarisation with the sectarianisation and the ghettoisation of Belfast in that period.

"The barricades go up and they don't really ever come down."

Bettmann/getty images

Bettmann/getty imagesEamonn McCann said no-one foresaw 30 years of conflict following on from the Battle of the Bogside.

"The civil rights movement had been on the streets for more than a year," he said.

"Their demands were basic democratic demands which could have been conceded within the existing political arrangements had the unionist government or London been foresighted enough to see it.

"I didn't think the state would be so stupid as to do what they did."

Read more: Explore in depth the events that led to tensions spilling over into violence