Karen Bradley: What went wrong for the outgoing secretary of state?

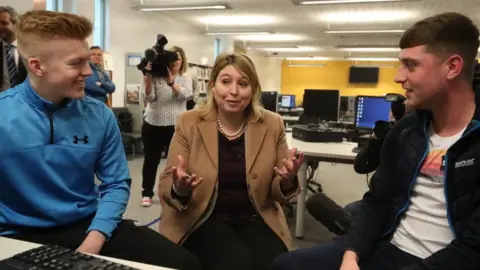

PA

PAKaren Bradley's departure as Northern Ireland secretary comes as no surprise to many.

As she leaves, the return of devolution at Stormont seems further away than when she accepted the job 19 months ago.

She has also infuriated survivors of historical abuse, enraged some Troubles victims and was lampooned for her lack of understanding of Northern Ireland voters.

So what went wrong for Karen Bradley?

"Attracting widespread and sustained criticism, Karen Bradley united the political classes in their belief that she was inept, ineffectual, gaffe-prone and completely out of her depth," said Deirdre Heenan, professor of Social Policy at Ulster University.

"However, from Theresa May's perspective she was a rare commodity - a loyal and trusted colleague."

Pacemaker

PacemakerIt is fair to say the 49-year-old Staffordshire native probably never expected to find herself in charge of Northern Ireland.

She had never set foot in the place before Mrs May appointed her as secretary of state on 8 January 2018.

Mrs Bradley was on a plane to Belfast the next day and said it was fitting that her first official visit was to the city's Titanic Quarter, as it represented Northern Ireland's past and future.

Her priority was of course to stop Stormont from sinking, not an easy task as her maiden voyage coincided with the first anniversary of devolution's collapse.

PA

PAA full year had passed since the late Martin McGuinness pulled the plug on Sinn Féin's power-sharing coalition with the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), and the parties remained bitterly divided.

Undeterred, Mrs Bradley insisted on her first day: "I understand the importance of dealing with the past and securing a safe and prosperous future."

Her very limited understanding of Northern Ireland's history and traditions was later painfully exposed, by none other than herself.

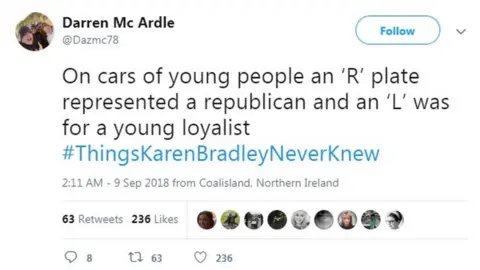

#ThingsKarenBradleyNeverKnew

In September 2018, she gave an interview to a Westminster magazine, The House, which drew incredulity as well as criticism and ridicule.

"I freely admit that when I started this job, I didn't understand some of the deep-seated and deep-rooted issues that there are in Northern Ireland," she said.

"I didn't understand things like when elections are fought for example in Northern Ireland, people who are nationalists don't vote for unionist parties and vice-versa."

Reuters

ReutersShe protested that her quotes had been taken out of context, but a frank admission of political ignorance from a senior politician was mocked by both mainstream and social media.

The hashtag #ThingsKarenBradleyNeverKnew trended on Twitter as users poked fun at her lack of local knowledge.

Twitter/Darren McArdle

Twitter/Darren McArdleAt the time of her appointment, the former accountant had been a Conservative MP for eight years.

She had held positions at the Treasury, the Home Office and the Cabinet. She led the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport immediately before her move to Belfast.

Her hasty appointment followed James Brokenshire's resignation. He had temporarily left the government to receive cancer treatment.

In March 2019, Mrs Bradley faced calls to resign when she told the House of Commons that Troubles-era killings at the hands of the security forces were "not crimes".

"They were people acting under orders and under instruction and fulfilling their duties in a dignified and appropriate way," she told MPs.

She later clarified and then finally apologised over the remarks.

It was not the only time Mrs Bradley upset victims of Northern Ireland's painful past.

In May 2019, survivors of historical child abuse accused her of using them as a tool for "emotional blackmail" in talks to restore devolution.

The victims have been waiting for state compensation since January 2017, after payments were recommended by the Historical Institutional Abuse (HIA) Inquiry.

Mrs Bradley angered campaigners when she suggested adding the HIA payments to the list of issues to be resolved by the Stormont talks process.

PA

PAThe secretary of state then sought separate agreement from Stormont's main parties on compensation, but the long-delayed legislation is yet to pass through parliament.

Media appearances by Mrs Bradley became infrequent and brief.

She declined to answer journalists' questions over the ongoing talks to restore Stormont, drawing criticism from both the National Union of Journalists and her party's allies, the DUP.

DUP MP Sammy Wilson contrasted her refusal to take questions at Stormont with a lengthy press conference given by Tánaiste (deputy prime minister) Simon Coveney.

Mr Wilson claimed she was "allowing the impression to be given that these talks are being driven by the Irish Republic".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy early June, the secretary of state tried a different tack and invited MLAs to a summer drinks reception at Stormont House.

But instead of oiling the wheels of power-sharing, parties snubbed the event and it had to be cancelled.

Responding to news of her departure, Mrs Bradley said she was "extremely proud of our achievements over the last 18 months" and regrets not concluding the talks process.

"I now pass this tremendous responsibility over to my successor with every best wish and my full support to conclude the process."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite the unresolved political stalemate, Prof Heenan argues that Mrs Bradley was "successful" in one sense because she "managed to keep Northern Ireland out of the PM's in-tray".

"Mrs Bradley kept the place ticking over with minimal intervention, thus protecting the embattled PM from the additional headache of Northern Ireland."

She may have won few fans, but the refusal of both Sinn Féin and the DUP to compromise in the ongoing talks will not make the post of secretary of state for Northern Ireland any more attractive to her successor.