Children's hospital deaths were avoidable

BBC

BBCAn inquiry into the deaths of five children in Northern Ireland's hospitals has found that four of them were avoidable.

The findings followed a 14-year inquiry into hyponatraemia-related deaths.

Hyponatraemia is a medical condition that occurs when there is a shortage of sodium in the bloodstream.

The damning report was heavily critical of the "self-regulating and unmonitored" health service.

The Belfast, Southern and Western health trusts said they "unreservedly apologise" to the five families.

Mr Justice O'Hara was scathing of how the families were treated in the aftermath of the deaths and also of the evidence given to the inquiry by medical professionals.

He said that "doctors and managers cannot be relied on to do the right thing at the right time" and that they had to put the public interest before their own reputation.

He also said that some witnesses to the inquiry "had to have the truth dragged out of them".

The inquiry was set up in 2004 to investigate the deaths of Adam Strain, Claire Roberts, Raychel Ferguson, Lucy Crawford and Conor Mitchell.

The chairman said that the deaths of Adam Strain, Claire Roberts and Raychel Ferguson were the result of "negligent care".

In his report, Mr Justice O'Hara found that:

- while investigating the death of Adam Strain, the inquiry had been met with "defensiveness and deceit" and that "information was withheld" about what happened to Adam in the operating theatre

- there "was a cover up" in the death of Claire Roberts, whose death was not referred to the coroner immediately to "avoid scrutiny"

- poor care was "deliberately concealed" in the death of Lucy Crawford

- there was a "reluctance among clinicians to openly acknowledge failings" in the death of Raychel Ferguson

- in the death of Conor Mitchell, there was a "potentially dangerous variation in care and treatment afforded to young people at Craigavon Hospital"

In total, the inquiry made 96 recommendations including the establishment of a duty of candour on medical professionals "to tell patients and their families about major failures in care and to give a full and honest explanation".

Mr Justice O'Hara added that the "reticence of some clinicians and healthcare professionals to concede error or identify underperformance or colleagues was frustrating and depressing".

Marie Ferguson, the mother of Raychel, said that the inquiry was "confirmation of what we knew happened".

"She went into hospital as a young, healthy girl and was neglected by the nurses, neglected by the doctors and, ultimately, died because of the negligence of those we consider health professionals."

Mrs Ferguson added that she had been devoted to finding the truth and "what I experienced during this journey is inexcusable".

"The trust and their lawyers abused their position by trying to cover up the truth. They robbed me of the most precious wee girl," she said.

"For hospital medical staff to make a mistake is forgivable, however, to orchestrate a cover-up and to deliberately mislead is totally unforgivable."

The family of Conor Mitchell said medical staff had "failed Conor so badly".

"The reticence with which the investigation has been handled by the trust and their advisers and the grudging way in which the limited acceptance of failings and minimal apology given were extracted, indicates a reluctance on their part to undertake the learning and the change in attitude needed to reduce the trauma caused in cases such as these," they said.

Analysis

by Marie-Louise Connolly, BBC News NI health correspondent

There was a real sense of regret, here, that for these five families, life should have been very, very different.

The report spans three volumes of almost 700 pages and, while each case is treated separately, overall the chairman refers to a catalogue of failings, where in most cases shortcomings were evident from the outset.

Sometimes with a great deal of emotion, Mr Justice O'Hara talked about the lack of professional candour, not just among clinicians but also by some managers.

There was a tremendous sense of grief and anger in the room. The mothers of Raychel Ferguson and Claire Roberts sat in the front row and sobbed throughout the chairman's findings.

A spokesperson for the Belfast, Western and Southern trusts said they would "urgently review" the recommendations to "ensure that all possible steps have been taken to prevent this ever happening again".

"We made mistakes, we were not as open and transparent as we could, and should have been, and opportunities to learn from each other to make our care safer were missed - for this we are truly sorry.

"Since these tragic deaths occurred significant lessons have been learned in how we safely manage fluids in children and many improvements have been put in place."

Cathy Jack, the medical director at the Belfast Health Trust, said all three trusts would comply with any individual rulings that might arise from the General Medical Council and added that, on a personal level, she was ashamed.

The Health and Social Care Board said: "Whilst we fully accept that it is cold comfort to the families, since the incidents leading to these tragic deaths, a number of significant changes have taken place within the wider health and social care system.

"A lot of work has gone into ensuring that when things do go wrong, incidents are reported, robust action is taken, families are engaged, and relevant learning is shared and disseminated."

The Department of Health said the "thoughts of everyone" were with the families of the children and it was "deeply sorry for the distress, hurt and loss suffered by the families".

"The inquiry report acknowledges the work that has been undertaken to address serious, past failings and provide safe and accountable care in future," it added.

"That vital work will continue, informed by the findings and recommendations of the inquiry report."

General Medical Council chief executive Charlie Massey said: "The inquiry raised some serious concerns - we will analyse these to identify any new evidence it has brought to light in relation to the cases considered.

"The GMC supports the introduction of a statutory duty of candour.

"It's vital that doctors and all other professionals are open and honest with patients and employers."

The Police Service of Northern Ireland said it noted the report into the inquiry had been published and would "take time to carefully assess its contents before deciding what action needs to be taken".

Cost expected to rise

The hyponatraemia inquiry has been dogged by repeated delays and adjournments.

The first witness was not called until April 2012 and it stopped taking evidence in November 2013.

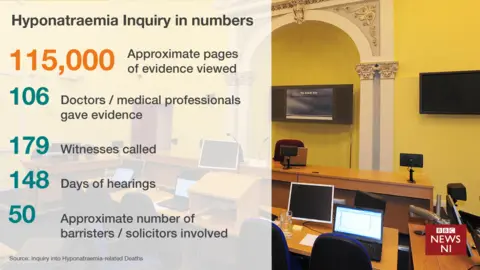

A total of 106 doctors and other medical professionals gave evidence and 179 witnesses were called.

Fifty lawyers were involved, representing the inquiry, the families and the health trusts.

Initial reports suggest the inquiry cost £13.5m, but that figure is expected to rise.