The lost history of Tynemouth's Holocaust safe house for girls

BBC

BBCNumber 55 Percy Park looks much like all the other town houses on a well-kept seafront parade in Tynemouth. But more than 80 years ago, it played a small yet significant part in the rescue of Jewish children from the Nazis.

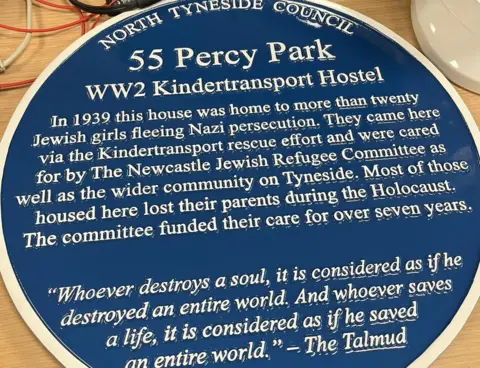

Following a BBC investigation, a blue plaque was unveiled on the house to commemorate Holocaust Memorial Day and to mark the property's forgotten past.

When Martin and Rosemary Anderson moved into their home in July 2017, they had no idea about what once took place within its walls.

"The previous owners, who'd lived here for a number of years, clearly didn't know because a unique bit of history like that would have been a good selling point," Martin says.

During World War Two, the Andersons' home served as a sanctuary for more than 20 Jewish girls who had fled Nazi persecution.

They came to the UK on the Kindertransport, the rescue effort in 1938 and 1939 which brought thousands of mostly Jewish refugee children to Britain.

The girls lived in the terraced house for about a year, but all trace of their presence there has since disappeared.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe story also appears to have been lost among Tyneside's Jewish community, which has dwindled in size since the 1940s but made a huge effort to rescue the girls.

"I think a lot of the Kindertransport was forgotten," says Brenda Dinsdale, honorary life president of Newcastle Reform Synagogue. "How old are the survivors now? We're an older community and there are very few people left who remember. We should have taken oral histories of these people but we didn't."

However, the house was well-remembered by those who found refuge in it. At least three of the girls from the hostel are still alive, BBC Radio Newcastle has discovered.

The youngest is Inge Hamilton (then Inge Adamecz), who came to the UK from Poland, in 1939, aged five.

She was photographed with her sister Ruth and another girl after arriving at Liverpool Street Station in a picture which became one of the defining images of the Kindertransport.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe has no memory of the photo being taken - nor does she remember her mother and baby sister who stayed behind and were later killed by the Nazis.

"People say I look like Shirley Temple but don't ask me why I'm smiling," says Inge, who now lives in south London.

"I don't understand how I could have been smiling after all that. Look at how serious my sister is. It really affected her."

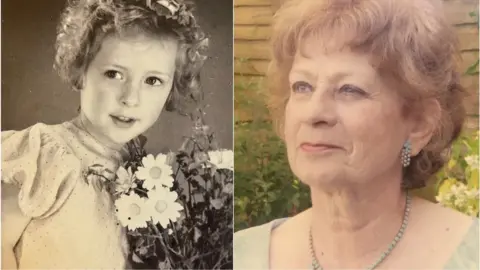

Inge Hamilton

Inge HamiltonDasha Caminer was seven when she left what was then Czechoslovakia for Tynemouth. She is now 91 and lives in Australia.

"It was a hostel, a community of young people that were thrown together because of awful circumstances," she recalls.

"We always hoped that next year, the war will be over and we'll have a normal life again. It didn't happen that way. But you have to get on with life and look for the good things."

Both her parents were killed while she was in the UK.

Another of the hostel girls was Alisa Tennenbaum, who is now in her 90s and lives in Israel. She was 10 when she left Vienna, in Austria, with the Kindertransport and remembers a frightening journey from London to Newcastle, a place she had never heard of.

"I was put on a train on my own and I was told to get off in Newcastle and I sat and cried and I repeatedly said 'Was ist Newcastle?'"

The story of Alisa and her fellow refugees' journey to the North East of England begins after Kristallnacht (the so-called night of broken glass) in November 1938 when Jewish homes, businesses and synagogues were ransacked throughout Germany and Austria.

Following the attacks, the British government agreed to speed up the immigration process for children although there were strict conditions and their parents were refused refuge.

In Tyneside, a committee was formed to try to help, led by jeweller David Summerfield and his wife Annie. Their granddaughter Judith Summerfield was very young during the war but has vague memories of the time.

She says they wanted to open a hostel for girls who they thought were more vulnerable than boys, but it was a huge undertaking.

"Each girl has to be sponsored for £50 - the equivalent of about £3,000 today - at a time when there was very little money about," Judith says. "The house had to have the builders in, it had to decorated, they had to kit out the kitchen, and they had to recruit matrons to look after the girls."

The house was owned by Sylvia Fiskin, a member of the Jewish community.

It had been used as a holiday home but she was happy to hand it over, says her grandson Paul Stock.

For Sylvia it would have been an easy decision, he says. "There's a concept in Jewish law called Tikkun Olam - repairing the world - and there's also a concept of charity called Tzedakah.

"My grandmother would have been conscious of this and therefore it would have been the right thing to do."

Summerfield family

Summerfield familyThe girls were cared for by two women from Vienna, who were themselves fleeing Nazi persecution. One was the celebrated cook Alice Urbach and the other Paula Sieber, a successful businesswoman.

The girls were well fed but, as was the norm at the time, the matrons ran a strict regime, according to historian and Alice's granddaughter Karina Urbach.

She says: "[Alice] thought looking after children would be easy - she had two sons - and she thought it would just be for a very short time but it turned into seven years.

"When she looked at the children she knew she might have to tell them their parents would never turn up again.

"The letters stopped usually after the parents wrote to say they were to go on a long journey."

The girls stayed in Tynemouth until 1940 when it was decided it would be safer to move them to Windermere, in the Lake District.

The committee expected to look after them for a few weeks but instead paid for their care for seven years.

Nicola Woodhead, who is writing a PhD on the Kindertransport at the University of Southampton, says this was really unusual.

"A community of kinder being kept together for seven years was quite rare. If a hostel shut down, or they were forced to evacuate, often the children weren't kept together.

"Sometimes children were moved several times. You don't see many examples of a community funding a hostel, even after they were evacuated and paying for their upkeep and keeping them all together."

'Don't talk about past'

After the war, the girls were largely left to fend for themselves.

Most discovered their parents had been murdered. Many settled in other countries. Some - like Elfi Jonas, who died during the Covid pandemic - never spoke about their experiences.

Her daughter, Helen Strange, recalls: "Even when I went to school my mum used to say to me 'don't talk about your past'.

"I think as a child they'd been told the lower profile you kept the less likely you were to be discovered. Even very close friends had no idea of her background."

Elfi did keep in touch with her hostel friends though, and in 1988 some of them gathered for a reunion.

One of them, Ruth David, described it in her autobiography, A Child of Our Time. She wrote: "Oddly enough, in spite of our advanced years, we all saw ourselves as 'girls'.

"It was an unexpected delight. The intervening years made little difference. We were not among strangers".

In 2022, Ruth's daughter Margaret Finch and other descendants of those who lived in the house on Tynemouth, and those who had helped them, gathered there for their own reunion.

For Margaret it was a chance to offer her thanks, as she believes her mother would have wanted. "Without the kindness of the Jewish community here, it's unlikely these girls would have got places on the Kindertransport," she says.

"They would probably have faced the same fate as most of their parents - to have been murdered by the Nazis. As a child, my mother was too miserable to recognise that but later in life she came to realise what the community had done for her and the other girls.

"She was very grateful."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].