Bishop Auckland exhibition shows art through soldiers' eyes

Mick Grahgam

Mick GrahgamWar and art are not new bedfellows - think of the poems and sketches created in the World War One trenches - but a new exhibition in County Durham is highlighting the works created by the modern military veterans. What sort of art are they producing and why?

The art of PTSD

Lonely Tower Film and Media

Lonely Tower Film and MediaOn 8 August 1970, 17-year-old John Cutting joined the Army.

Five years later, after being stationed in Northern Ireland "at the height of the Troubles", he left facing a lifelong battle with complex post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

What so affected him was not the sniper shots or close-call bomb blasts, but rather the "constant, intense abuse" he received while patrolling the streets.

"People were screaming and spitting at us. They looked like me, talked like me, dressed like me and yet they wanted to kill me," he recalls.

He likens the psychological effect of that to the impact of child abuse.

"PTSD is a fear of what's going to happen to you. When I go out, my sub-conscious thinks I'm still in Belfast even though my conscious knows I am not."

He is in a constant state of exhausting "hyper-vigilance", John says.

BBC

BBCThe triggers for him are "trivial", like an awkward exchange with someone in the street, but the effects are anything but.

He has contemplated suicide, deterred only by the thought of what would happen to his dog Alfie.

Four years ago he had a moment of inspiration in which he created a horse's head from horseshoes for his granddaughter, and he realised he had discovered art.

He credits it with saving his life.

"The biggest killer is ruminating," he says. "Art has become my focus instead, it stops me thinking of other things.

"It's not art therapy, it's an art obsession."

BBC

BBCWith the financial backing of Style for Soldiers and the Army Benevolent Fund, he has completed a degree in fine art and is now studying a masters at York St John University.

Three of his works can be seen at the Through Soldiers' Eyes exhibition in Bishop Auckland Town Hall, and each is riddled with meaning.

One is a humanoid sculpture made from the used prosthetic limbs donated by the Ministry of Defence's veterans' rehabilitation centre.

Another is a representation of a paratrooper made from building materials. This was inspired by his meeting with the family of a paratrooper who died and after the exhibition ends he intends to gift the piece to them.

The third is a life-size stag made from a clothes rail and coat hangers.

He says the stag is intended to convey the common ground people all around the world share - a love and need of shopping - although he also says people should "create their own stories" from his work.

BBC

BBCHe mainly uses bits and bobs scavenged from skips and beaches.

He says his PTSD has helped with his art, because his hyper-alert brain wants to make what, to him "does not look right" and potentially dangerous, appear non-threatening.

John hopes his progress can also change public perception of "drunk, homeless veterans".

"It's easy to condemn them and write them off, but it's so easy for someone to fall into that way of life," he says, adding: "These veterans are dealing with something they cannot really control.

"I want the message to be that people with mental health issues like me can be productive, we can have a positive existence."

Army communications

BBC

BBCBeing a soldier and creating art are a natural fit for Paul Cappleman.

"In the army you tend to be very kinaesthetic - hands on, and art is also very hands on," the 58-year-old says.

"Once you start doing something with your hands you are so concentrated on it that it takes whatever hassle you are having in your brain, be it PTSD, depression, flashbacks, and puts it far away in a little box."

The 58-year-old joined the Junior Regiment Royal Signals at 16 and went on to serve around the world, from Northern Ireland and Bosnia to the Falklands and the Gulf.

BBC

BBCHis job was laying communications lines - "a BT engineer with a gun" - and he says the "wear and "tear" of lugging cable drums around eventually saw him medically discharged 23 years and 69 days after he signed up.

He has undergone numerous surgeries and for years was on a cocktail of powerful painkillers before deciding to use art as a distraction.

"I was a guidance officer in a prison in Northallerton helping inmates come off drink and drugs and distraction therapy was something we found really useful," Paul says.

"I just decided to follow my own advice."

BBC

BBCHe began painting in 2016, since when he has completed a degree in fine art and become an art tutor.

His exhibition paintings contrast his current family life with vivid memories of his past in the forces.

One is a beach scene, featuring his children playing in the sand beside a soldier in full chemical warfare gear in a desert.

Another shows children playing with sparklers near a bonfire merging into the smoke billowing out of the Sir Galahad, an RFA ship sunk during the Falkland War.

"I was watching my children play and the way the smoke from the bonfire was drifting just took me straight back to how the smoke was blown by the helicopters to clear the way for people to escape the Sir Galahad," he said.

BBC

BBC"The flashbacks aren't always a bad memory and everyone has them, not just soldiers.

"Whatever walk life you are in, you are formed and governed as to how to react to things by the things you have done and experiences you have had.

"Soldiers are no different, it's just the jobs we have been asked to do are maybe a bit more intense, nearer the knuckle."

One of the main purposes of art is "communication", Paul says, which is why it is a useful tool to share experiences and perspectives.

"It's about showing how I maybe see things a bit differently because of my experiences, and understanding how experiences shape everyone of us."

Tanks for the memories

BBC

BBCMick Graham aims to "conjure up memories" for his fellow tank veterans, wanting them to be able to "smell the diesel" when they see his paintings.

The 61-year-old ex-tank driver and gunner's works are realistic depictions of tanks in atmospheric locations.

But to anyone who has spent a career working with these machines, his creations are a noisy trundle down memory lane.

"That's what I feed off, making people feel that," he says, sitting in his dining room-turned art studio in Chester-le-Street.

"Also, I just like making tanks look cool. Forget your boy racers with their loud exhausts, when you were on a tank you were a real poser."

Mick Graham

Mick GrahamHis father was in the 4th Royal Tank Regiment and Mick grew up playing on the old tanks they used for target practice.

He ended up joining the same regiment in 1979 at the age of 19 and could drive a tank before he passed his (car) driving test.

Mick served in Germany during the Cold War but was never called into action.

Being in the military was "absolutely brilliant," he says, adding: "The camaraderie is just mind-blowing. The loss of that is one of the hardest things to deal with when you leave."

Painting had always been a hobby, but almost six years ago people started to notice his works on Facebook and he began to get commissions.

BBC

BBCHe points to a painting on the wall showing a chieftain tank which, Mick says, was notorious for having engine trouble. On the ground beneath it is a tray to catch the frequent oil drips, the sort of detail easily missed by a civilian but which adds a level of realism to those in the know.

"The most important thing is accuracy," he says, adding: "My audience is very picky, if even a small detail is wrong they will complain about it."

As well as impressing tank enthusiasts, veterans and historians, Mick's work has also been given the stamp of approval by Royal Mail.

It commissioned him to create eight stamps as part of a celebration of military vehicles, and he is bemused by the fame is brought him.

"At shows and tank festivals people ask me to sign their stamps," he says with a chuckle.

He is entirely self-taught and modestly describes his talent as "being good at colouring in".

Mick Graham

Mick GrahamHe paints for hours a day, often into the small hours, with the full support of his partner Marian, with each work taking up to three months to complete.

He says he has been asked before about the ethics of glamourising deadly weaponry, but says what he paints are magnificent machines on training exercises.

The nomadic optimist

Hazel Oakes

Hazel OakesFor Hazel Oakes, the military meant two things - travel and a sense of community.

The 31-year-old was a military child, her father John Oakes was in the Royal Signals, and she was born in Catterick, North Yorkshire, before going on to live in Cyprus, Germany and Belgium.

"I always loved moving around, making new friends and learning new things," Hazel says.

That wanderlust has never left her, and since graduating from Northumbria University with a degree in fashion design, where she was also in the university's Officer Training Corps, she has lived in France, Australia and Canada and is now in Italy.

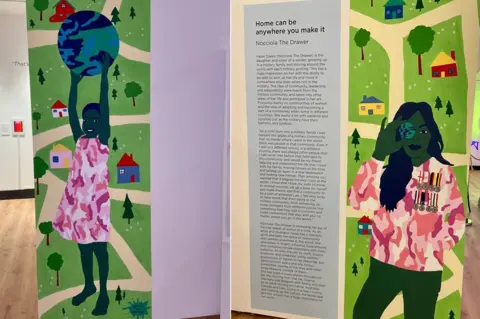

Her experiences are reflected in her work at the exhibition, two giant murals painted either side of a wall - the bright colours applied directly to the brick work being a rebellion against the strictly magnolia interiors of her childhood army camp homes.

Hazel Oakes

Hazel OakesOne side shows a child with the world in her hands, painted in the blues and greens of her father's regiment, while the other is an adult sporting medals, the ribbons of which are comprised of the colours of the places Hazel lived.

"Medals are important in the military," Hazel says, adding: "They mark significant achievement, and for me my achievement was getting to know the world.

"I wanted to represent growing up and how the military shaped my outlook on the world,"

The pink camouflage both figures are wearing is a nod to the military women in "a system historically created by and for men".

Hazel's is a very positive portrayal of military life, the excitement of going to new places and being part of a large community.

"Everyone's experiences of the military are very different," she says.

Hazel Oakes

Hazel Oakes"Seeing the art of people who have been through major trauma is so important to help others try and understand.

"In my background there has always been a knowledge about danger, but I was never actually in danger and I have a really optimistic outlook on life which I want to show in my work to hopefully inspire and empower others."

Once the exhibition is over, her mural will be painted over in readiness for the next display.

"The thing I like about murals and wall art is you do not know who will see it or what impression it will make, and then it is gone," she says.

"It's like being in the military. When you move to another place it's up to you what you leave behind and what you take with you."

The paratrooper poet

BBC

BBCIt was Craig's therapist who suggested he get back into poetry, and she saved his life.

She had asked him to look back to a time when he was genuinely happy, part of his treatment after suffering significant trauma both in and out of the army.

That night he went home and opened a suitcase that he used as a memory box. There were tears at the photos of his now dead mum and dad.

And then he found the newspaper clipping showing an 11-year-old Craig being named the winner of a Littlewoods poetry competition.

That was when he had been happy, so that is the time his therapist said Craig should try and recreate.

"The first time I tried doing poetry again it was just words, but it felt good, I was getting all my dark thoughts out," Craig, now a 42-year-old fitness fanatic helping other veterans and their families re-engage with sport through the Newton Aycliffe-based Sporting Force, says.

It showed him he could be happy again.

Craig had joined up when he was 16, and at the age of 20 was on the verge of joining the army's England rugby Under-21 team.

But just a week before his team trial, everything came came to a shuddering halt when a parachute malfunction found him falling 3,000 feet to danger.

The crash-landing smashed both his ankles, broke multiple bones in his legs and fractured his spine.

Two years of physical recovery followed, in which he had to learn to walk again, along with harrowing flashbacks.

Craig was medically discharged and left suddenly without a career, without friends and without direction.

Black book

Homelessness, bankruptcy and family break-up followed.

He did enjoy success as salesman and working in schools, but at night he would drink two bottles of wine a night mixed with a cocktail of powerful pain killers.

"I was a high-functioning alcoholic," he says.

Now, having found purpose with Sporting Force and an ability to truly empathise and help other veterans, including early leavers like himself, he is 12-and-a-half months sober and being a better dad for his three children.

Everyday he learns something new and does an act of kindness so that every night he goes to bed a wiser, nicer man.

Not all of his poetry is for sharing, he has a black book that is full of the darkest stuff.

"If I'm a bit low I read it to remind myself that it has been worse before and I have got through it," he says.

BBC

BBCBut one of his pieces is in the exhibition, created during a poetry and creative writing course he helped organise during the lockdowns.

Art and sport serve the same purpose for veterans, Craig says.

"They save lives," he says, adding: "When you are engaging in an activity that's your focus.

"Say a cricket ball is being thrown at you, that is all you are thinking about. There's a feel-good factor.

"Even if it just for half an hour, that person feels good, and they have got some hope back that actually they can have a better life.

"There is light at the end of the tunnel, there is a future."

Through Soldiers' Eyes is on at Bishop Auckland Town Hall until 20 November.