Stockton and Darlington Railway: What's so special about a 200-year-old railway?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwo-hundred years ago, work began on the Stockton and Darlington Railway (S&DR). According to its supporters, it is the railway that changed the world, but what makes it so significant and how much of it still exists?

What's so special about the Stockton and Darlington Railway?

"The steam railway world is full of pedants," Niall Hammond says with a laugh. "So I have to be careful about how I answer that.

"We would argue that it's the railway that got the world on track."

According to the chairman of the S&DR Friend's Group, what the S&DR did was, for the first time, bring together various elements of engineering and ideas for what a railway could be, which gave the rest of the world a blueprint for how to build a recognisably modern railway.

"It set the DNA for the railway system," said Anthony Coulls of the National Railway Museum.

Friends of S&DR

Friends of S&DRFrom the outset, it was much more than just a way of conveying coal, unlike many of the other early railways.

Transport of other goods and regular passenger services were intrinsic parts of the S&DR's creation.

It used a combination of horses, stationary steam engines and steam-powered locomotives to pull wagons along its 26 miles, from the coalfields of County Durham to the port on the River Tees at Stockton, via the-then village of Shildon and market town of Darlington.

Signalling systems, timetables and the idea of stations were all developed by the S&DR.

Engineers travelled from across Britain and the world to see the the railway in action, to replicate its successes and learn from its mistakes.

Bigger railways, such as the Manchester to Liverpool line, followed soon after and within a decade there was a global "railway mania", akin to the rapid development and impact of the internet in the 20th Century, Mr Coulls said.

"The S&DR was not the first railway and it was rapidly eclipsed. But it proved the practicality of the steam locomotive pulling trains over long distances."

What happened 200 years ago?

On the afternoon of 27 September 1825, a large crowd watched in awe as a train of more than 30 wagons steamed slowly but surely into Stockton, pulled by the gleaming new Locomotion No 1.

Twelve of the wagons, brimming with coal, had started the day more than eight hours earlier and 26 miles (42km) to the north west in Witton Park.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThey had been joined in St Helen Auckland by a wagon of bulging flour sacks, then in Shildon by up to 600 people crammed into 21 coal wagons fitted with seats and a single purpose-built passenger carriage called Experiment.

The route was lined with spectators, with an estimated 10,000 waiting to welcome the convoy into Darlington.

The train, frequently flanked by jubilant horse riders, ranged in speed from a sedate 4mph (6km/h) to a dizzying 15mph (24km/h).

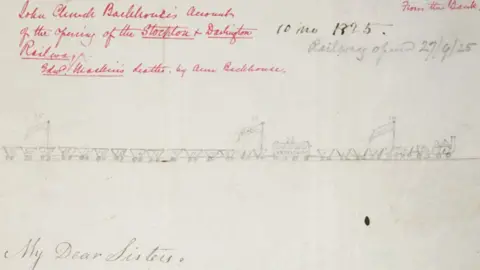

Jonathan Backhouses, an eight-year-old onlooker, later wrote to his sister that it was a "very grand sight to see such a mass of people moving".

National Railway Museum

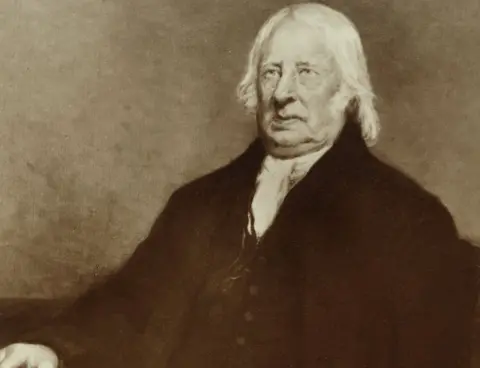

National Railway MuseumBut the story really starts in earnest four years previously on 19 April 1821, when two things happened.

The first was mine owner Edward Pease finally getting the act of Parliament he had spent three years fighting for, having overcome the objections of the gentry who did not want to sell him the land he needed for the proposed route of his horse-drawn railway.

Getty Images

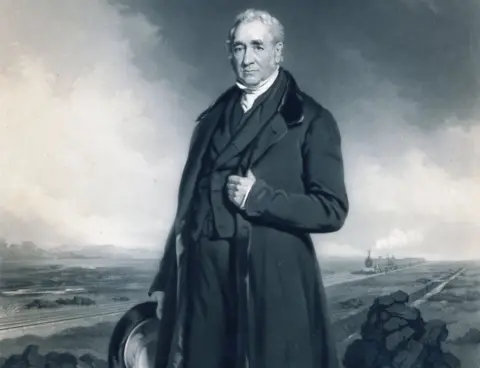

Getty ImagesThe second was the arrival at Pease's Darlington home of engineer George Stephenson, who convinced the businessman to discard the plans he had already spent time and money on in favour of his own vision for a steam-enabled railway.

Stephenson, who was building an eight-mile long steam-powered railway to move coal at Hetton Colliery, recognised that Pease's proposed line could be a whole transport system for goods and people.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOn the day Pease finally won permission to build a railway, Stephenson effectively came along and offered to build something even bigger.

That "fateful meeting changed everything" and "showed amazing forward thinking", according to Giles Proctor of Historic England.

For Pease to agree to Stephenson's vision, which would incur further costs and delays, was an act of bravery, according to Mr Hammond.

"That is why 19 April 1821 is so significant."

How much of the railway still exists?

About 20 miles (32km) of the railway is still in use, forming the basis for the Northern Rail services between Shildon and Stockton.

Original features include the Skerne Bridge in Darlington, said to be the world's oldest purpose-built railway bridge still in use and which featured on the £5 note in the 1990s, as well as paintings celebrating the railway's inaugural journey.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFive pubs built as "proto-stations", places for passengers to wait for their trains, also still exist, according to Mr Hammond.

These include the Masons Arms in Shildon, which is now an African themed restaurant, Kings Arms in Heighington (now closed) and the Railway Tavern in Darlington.

Cleveland Bay, which marked the terminus of branch line to Yarm, is said to be the world's oldest railway pub still in use, while the buildings which once housed a ticket office and tavern on Bridge Road Stockton are now a hostel for the homeless.

Peter Giroux

Peter GirouxSeveral S&DR-linked buildings can be found around the Locomotion Museum in Shildon, including the house where the railway's engineer Timothy Hackworth lived and worked, while there is also a goods shed next to North Road Station and Head of Steam Museum in Darlington that dates back to the railway's early days.

For Mr Coulls of the National Railway Museum, the most interesting remains can be found in the railway's first 5 miles (8km), between Witton Park and Shildon, which quickly fell out of use as the railway expanded and technology rapidly improved.

Through this section, horses pulled the trains along the flats while stationary engines were used to haul the wagons up the two inclines of Etherley and Brusselton.

At the latter, the remains of a large earthy bank lead to railway cottages and a reservoir used by the stationary steam engine.

Mark Ingelby

Mark IngelbyThe stone footings of a bridge across the River Gaunless near West Auckland can still be easily found while the ironwork is at the National Rail Museum in York, although plans are afoot to move it to Shildon.

National Railway Museum

National Railway MuseumFurther north there is a tree-lined public footpath along the Etherley incline, a large embankment striding high across the countryside towards the terrace of Phoenix Row and village of Witton Park.

Along the route, the large stones which supported the original iron rails can still be found scattered in the undergrowth.

What is planned for the bi-centenary?

Friends of the S&DR have already started their preparations for the big anniversary in 2025, including the creation of a series of booklets about walks along the railway's route.

One of its aims is to create a full walking and cycling route, complete with original S&DR pubs to stop at for refreshments, between Witton Park and Stockton, within the next 10 years.

Meanwhile, Locomotion Museum in Shildon, a branch of the York-based National Railway Museum, has plans for a new £4.5m building with space for 50 engines due to open in the run up to the 2025 anniversary.

Head of Steam is also set to undergo a major redevelopment to become the centrepiece of Darlington's Railway Heritage Quarter.

The whole route is already subject to a Historic England Heritage Action Zone, which is being surveyed to help realise "a major heritage attraction and visitor destination in the build up to its 2025 bicentenary".

More details of the celebrations will be announced over the coming years, but on Monday an event will be held in Darlington get the ball rolling.

Mayor Chris McEwan has invited other cities and towns around the world with strong railway heritages to join an online conference to mark the bi-centenary of the historic meeting between Pease and Stephenson.

"What they did 200 years ago was special," he said.

"You cannot argue against the view that railways and passenger rail were a force for good.

"They had a transformational impact on the world."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].