Guildford pub bomb inquest family 'never going to get justice'

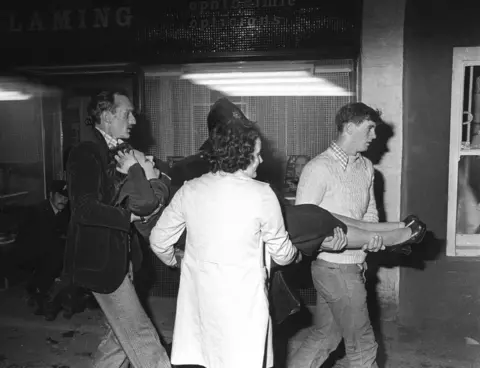

Terry Fincher

Terry FincherA woman who lost her soldier sister in the Guildford pub bombings has said her family are "never going to get justice" even though the inquest has resumed.

Cassandra Hamilton, whose sister was killed in 1974, said she had considered giving up after legal aid was refused.

Liberty and Inquest have criticised the decision as unjust when the police, Ministry of Defence (MoD) and coroner would have publicly-funded legal teams.

The government said families would be supported by the coroner.

But leading barrister Michael Mansfield QC said legal aid cuts were a "disgrace".

While Ms Hamilton has described the situation as "like hitting a brick wall", those close to the wrongly-jailed Guildford Four, including Bridie Brennan, sister of Gerry Conlon, have said they felt "back to zero".

Relatives 'silenced'

When the full inquest finally takes place, it is likely only the coroner, police and MoD would be in the courtroom because Ms Hamilton said her family may not attend and their lawyers, who have been working for nothing, may not be there.

It is thought only one of the victims' families sought to be represented, while of the Guildford Four and their families, only Paddy Armstrong sought active involvement but was rejected.

"The longer it goes on, the more I think just forget it. It's not going to change anything," Ms Hamilton said.

Handout

HandoutThe government has said the coroner could question witnesses on behalf of the relatives but Emma Norton from Liberty said that would be "disingenuous to families".

Deborah Coles, from Inquest, said state lawyers would defend the police and MoD at public expense, while relatives, without representation, "will be silenced".

Ms Hamilton's lawyer, Christopher Stanley from KRW Law, asked: "Why should an individual fund themselves to investigate the death of their loved one?"

At a recent pre-inquest review, Surrey coroner Richard Travers said he had written to the Legal Aid Agency in support of the family's application for funding.

A Ministry of Justice spokeswoman said: "Our thoughts are with the families of the victims of the Guildford pub bombings as the inquest resumes. They will be supported by the coroner who can ask questions on their behalf to help ensure they get the answers they need.

"Around two-thirds of applications for legal aid at inquests are approved and we are making wider changes to better support bereaved families."

No date for the full inquest has yet been set but the next pre-inquest review is scheduled for 26 February.

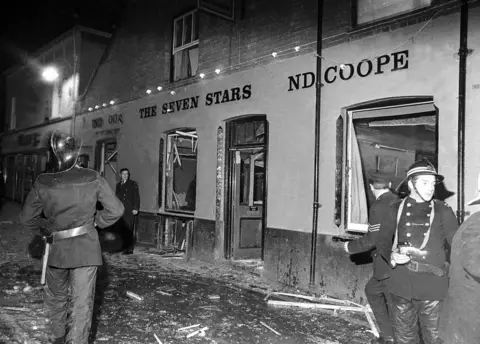

Terry Fincher

Terry FincherMs Hamilton was aged two when she lost her sister, Ann Hamilton, who was 19.

She was too young to remember her sister but said she did recall growing up with a family hit by trauma.

At the age of four, she lost her father who, she said, died of "a broken heart" following the bombings, which saw the IRA blow up the Horse and Groom and Seven Stars, killing five people and injuring 65.

The family has kept a scrapbook of photographs and cuttings documenting the atrocity but she finds it too painful to look at.

Ms Hamilton said the family sought legal aid to instruct lawyers to ask whether there were enough police on duty that night, whether they could have reached the scene earlier to save lives, whether her sister's barracks should have been on lockdown with the IRA already active on the mainland, and why the real bombers had not faced justice.

The provisional scope set out by Mr Travers covers who died and where and how they died - but not who bombed the pubs, whether police lied, and links between the Guildford explosions and other IRA bombings.

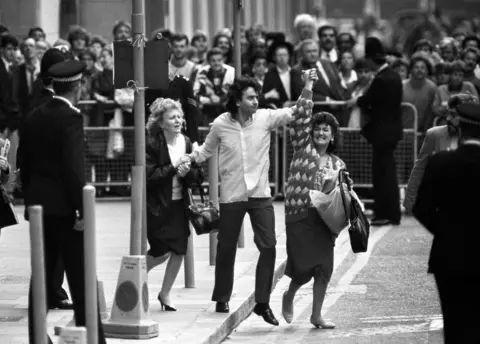

PA Media

PA MediaIn Belfast, Bridie Brennan saw her brother Gerry Conlon serve 15 years in jail before his conviction was quashed. Her wrongly-convicted father, Guiseppe Conlon, who had tuberculosis, died while still serving his 12-year term.

He was one of the Maguire Seven - all family and friends of the Conlon family. The Maguire Seven were wrongly-jailed on explosives charges, while the Guildford Four had been falsely accused of murder.

Mrs Brennan said she had her "heart setting on being at the inquest" because she hoped it would reveal the truth and clear her family of suspicion.

When the inquest resumed, Mrs Brennan said: "We actually thought there was going to be a breakthrough."

But after it emerged that only the authorities would have lawyers and the inquest would not look at wider questions, Mrs Brennan said: "We are back to square one."

Thirty years after her brother's release in 1989, she has sought legal aid for her own legal action against authorities in England and Northern Ireland.

Her solicitor, Kevin Winters from KRW Law, said it was believed information that could have exonerated Mr Conlon, who died in 2014, at the time of his arrest was "suppressed" by police when they moved him from Belfast to Surrey for questioning.

PA

PAOf those campaigning over the Guildford Four, former Republican prisoner Ricky O'Rawe, who has published a biography of Gerry Conlon, has branded the inquest a "rubber stamp job".

Alastair Logan, a lawyer who represented the Guildford Four, said in the light of "massive" non-disclosure, the "chaos" of documentation and Surrey Police managing to destroy papers, the inquest could have become an Article 2 inquiry, which would see a coroner look at the wider circumstances of how people died and any human rights breaches.

More than 700 files on the bombings have remained closed and Mr Logan has repeatedly spoken out against the continuing secrecy.

The files were due to open on 1 January 2020 but the BBC understands they are now subject to further closures, some for another 100 years.

The BBC has submitted a Freedom of Information request to the National Archives to confirm the opening dates but public interest tests will continue into next year.

Getty Images

Getty Images'How much was known?'

QC Mr Mansfield, who has represented the Birmingham Six, said "big questions" remained over the police investigation, including how officers reached the conclusions they did and overlooked the actual culprits.

He said families had to ensure questions were asked and it was up to them to "push the boundaries", for which they would have needed separate and funded representation.

"Where in all this were the anti-terror squad and Special Branch?" he asked. "How much intelligence was known? They had already had attacks in London and bombings before Guildford.

"They must have been alerted to the possibility there might be more instances. What were they doing to protect the public?"

Bomb squad commander Bob Huntley wrote in 1977 how, after attacks on London in 1973, plans were made to ban the IRA but Scotland Yard believed it was better for the IRA to operate on the surface. Police watched their meetings, noted who went on marches and kept dossiers on supporters.

But he said after the IRA bombed Birmingham on 21 November 1974, the government had "no choice" but to act.

The Prevention of Terrorism Act was announced on 25 November and enforced on 29 November, when Special Branch clamped down on ports and airports. By that point, a blacklist of nearly 1,000 IRA suspects had been drawn up, including about 20 confessed organisers in London and the Midlands.

Mr Logan said the action taken on 29 November could have happened sooner: "They should have done it before Guildford. There had been a bombing in Aldershot - there was plenty of reason for them to be looking at it before 1973. What if this work had been done earlier?"

Terry Fincher

Terry Fincher