RSPB Minsmere: WW2 sea defences emerge from Suffolk beach

Stuart Howells/BBC

Stuart Howells/BBCIn 1940 the British high command became increasingly fearful of a German invasion by sea. In the months that followed, some of England's most beautiful beaches were turned into battlefields that would never see action. In recent days, a slice of that wartime history has re-emerged thanks, in part, to the easterly winds which have caused temperatures to drop.

Today, the reserve at RSPB Minsmere on the Suffolk coast is a 2,500-acre habitat for more than 6,000 species.

Eighty years ago, Minsmere was a very different place.

As with many other beaches along the East Anglian coast, it had a minefield, concrete blocks intended to slow advancing tanks, trenches and a huge scaffolding structure that was meant to rip through the hulls of advancing landing barges.

Eric Hosking Charitable Trust

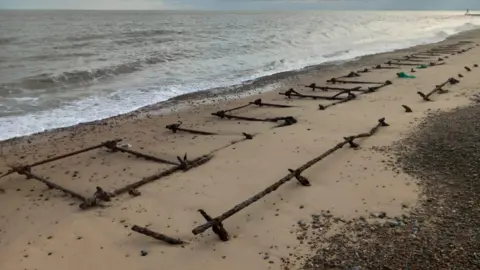

Eric Hosking Charitable TrustIn recent days, the remnants of that scaffolding, which once stood 3m (10ft) high, has re-emerged from the sand.

According to warden Dave Thurlow, the reappearance of parts of the Z1 naval scaffolding is largely down to the easterly winds which have shifted away some of the shingle.

It is not the first time Minsmere's World War Two history has been unearthed. A similar thing happened in 2013 before the tides and the wind covered the scaffolding remains once again.

Stuart Howells/BBC

Stuart Howells/BBC"It is pretty rare to see it, having survived in this form," said Mr Thurlow.

"I think when they cleared the scaffolding away after the war they just sawed it away. A lot of the scaffolding that was taken down could not be reused because it had been exposed to the elements, so they just buried it.

"When I've been looking out over the beach here, I've had the occasional curious person asking me about it and what it is.

"Most of the time, it is completely buried but when you get certain tides and the easterly winds, it will strip of all the shingle and this is what you see."

Prof Robert Liddiard, of the University of East Anglia, said the types of defences put up at Minsmere followed the German invasion of the Netherlands in May 1940.

"Once the Netherlands fell, there were concerns about ports in the low countries, such as Antwerp, being used as the base for an invasion," he said.

The British, he said, did not know whether such an invasion force would land on the south coast at Kent or Sussex, or on the East Anglian coastline.

"They started to go into something of a panic mode and you start getting pillboxes, barbed wire, minefields and the flooding of the marshes."

The scaffolding and so-called "dragon's teeth" (steel spikes set in concrete) quickly followed.

The East Anglian coast was felt to be particularly vulnerable because of the wide beaches and low-lying land surroundings which, said Prof Liddiard, were "good landing territory" for tanks.

"By late 1941, the area has become a prepared battlefield."

Stuart Howells/BBC

Stuart Howells/BBCWould these various defences have worked?

"That's the $64,000 question," Prof Liddiard said. "The intention here was to slow and disrupt and, to that end, I think they would have worked.

"How long they would have been held up for? We just don't know. What we do know is that the British troops had specific orders not to withdraw. They would have fought until the end.

"We tend to laugh at this stuff because it is a bit Dad's Army - it was not like that at the time.

"When the Admiralty tested the defences, they found it did its job reasonably well.

"However, it is an irony that a German invasion by sea was most likely to have taken place in June 1940 when the coast was at its most vulnerable. Once Germany had invaded Russia in June 1941, it [the invasion of the UK] is not going to happen."

Had Nazi Germany invaded, would they have landed on the east coast?

Not according to Prof Liddiard.

The evidence, he said, was that a German invasion, had it come, would have been on the south coast.

Robert Liddiard

Robert LiddiardProf Liddiard, who, with David Sims, wrote A Very Dangerous Locality: The landscape of the Suffolk Sandlings in the Second World War, said the soldiers sent to install the scaffolding did not enjoy the experience.

"The troops absolutely hated it," he said. "They were in the water, it was long hours and it was cold, hard, manual labour."

Gaps were left in the sea defences, he said, for fishermen to use.

Called "fishermen's gaps", these channels were sometimes used by brave locals who used them to take a swim in the sea.

"I once spoke to an elderly lady at Sizewell who did just that," said Prof Liddiard. "She remembers her mother telling her not to leave the path because of the minefield."

The minefields of the East Anglian beaches were extremely dangerous.

"They were horrible," said Prof Liddiard. "The sea would move them around the place, sometimes the sea would set them off and there were cases of soldiers, civilians and, sometimes dogs, inadvertently setting them off."

When World War Two ended, cadets were sent out to clear the mines.

Ian Barthorp/RSPB

Ian Barthorp/RSPBAnd while the remnants of the sea defences might continue to arouse curiosity from visitors to Minsmere, they are also a sign that the military clear up was not as thorough as it was on popular beaches such as Southwold and Aldeburgh.

"Places like Aldeburgh and Felixstowe, which were established coastal resorts, were desperate to get their tourism trade back," he said. "They needed the money.

"The minefields were cleared first followed by the barbed wire and the rest.

"They did a pretty good job of it and, by 1950, most of the big stuff had gone."

At Minsmere, the flooding of the marshes as part of the war effort has had a lasting legacy. It meant Minsmere had about 400 acres of watery pools with extensive reedbeds.

The defence of the United Kingdom had accidentally created a haven for wild birds which eventually became the reserve as it is known today.

As for the remnants of the scaffolding, it is already beginning to be reclaimed by the shingle and will soon disappear once more.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. If you have a story suggestion email [email protected]