HMS Quentin: Father's diary reveals horror of WW2 ship's sinking

BBC

BBCA horrifying account of the sinking of a British battleship on 2 December 1942 has been rediscovered after having lain unread in a diary for almost 80 years.

Written by 21-year-old Navy medic Alfred Kirkham, the diary tells how HMS Quentin went down during a World War Two sea battle in the Mediterranean.

Before his death in 2003, he passed his diary to son, Frank, who finally read it and typed it up during lockdown.

Mr Kirkham, from Sheffield, said it was "emotional" reading his dad's journal.

"I can hear his voice saying a lot of these things in here and that's nice," he added.

Frank Kirkham

Frank KirkhamAlfred Kirkham's account of the Battle of Skerki Bank was written only about a year after his war had started in earnest.

Mr Kirkham, who was raised in Chinley, Derbyshire, joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve with a friend in 1941.

"They thought if they waited to be called up they would end up in the Army - and neither of them wanted to do that," explained his son.

Following basic training in Skegness, Lincolnshire, Alfred was posted to The Royal Hospital Haslar in Hampshire, where he trained to be what was known as a sick berth attendant.

Reading his father's journal, Frank Kirkham discovered Alfred was, in fact, the only sick berth attendant on board HMS Quentin during the Battle of Skerki Bank on 2 December 1942.

'One of last to leave'

The ship played a pivotal role in the action, which saw the Royal Navy attack an Italian convoy, but HMS Quentin was also herself attacked.

The British destroyer was left stricken in the Mediterranean after being hit either by a 500kg bomb or a torpedo and a total of 20 crew members died.

According to Mr Kirkham's diary, another destroyer, HMAS Quiberon, of the Royal Australian Navy, eventually "glided alongside" the British vessel and picked up survivors.

Frank Kirkham explained that his father "was one of the last to leave".

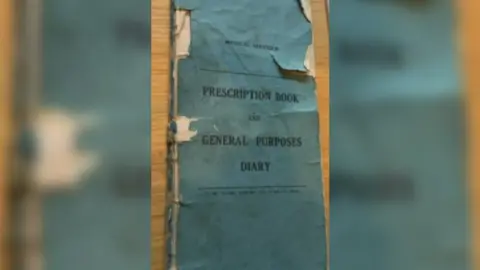

"But he had time to dash back to the sick bay and grab three things - his Bible, a photograph of my mother and this diary. Everything else went down."

Extract from Alfred Kirkham's diary - Wednesday 2 December 1942:

"0645 and all sleep was disturbed by a thunderous explosion followed immediately by the hiss of escaping steam. In a flash, we three occupants of the sick bay were climbing up to the bridge on the heels of nearer placed men. Quentin did not go down immediately, in fact there seemed a hope to save her. Knowing the danger was not immediate, we dodged back to the sick bay to be ready for casualties.

The first was a Derby man who was terribly scalded by steam. He was given morphine and left lying quietly on the sick bay couch. The second destroyer, HMAS Quiberon, swung towards us and glided alongside but, of course, did not stop. The scramble to get on board her commenced. It was difficult lifting badly injured men on board, but it was done. The poor chap who had been lying near the torpedo tubes where the torpedo struck was given a big dose of morphia and left. He was dying. Injured horribly.

We had hardly time to go to the sick bay before dive bombers swooped towards us unleashing their bombs. Imagine the disorder, the struggling, as 400 men sought cover and some place that would give easy access to the sea in case we were hit again.

To occupy my mind this time, I looked after a young torpedo man whose body was severely scalded all over and whose right leg was practically severed at the hip. The shock was too much. He died within the hour.

After World War Two, Alfred Kirkham left the Royal Navy and became a fire insurance surveyor.

In 1954, he moved to London where he went on to work for a leading firm.

Before his death, he gave his wartime journal to his son, Frank, who stored it in his study, vowing to one day absorb its contents.

'It was a bit grim'

Frank Kirkham said he decided to examine his father's faded war diary and learn more about his Royal Navy experiences during the Covid lockdown.

"There were not too many good things about lockdown in 2020, but I had time on my hands," Mr Kirkham said.

"So, I thought, I know what I'll do, I'll transcribe this diary, and I got out my magnifying glass and laptop."

He said it took him about three weeks, working two or three hours a day, to type up the diary entries.

He learned a lot as he worked on the journal as his father had spoken only "very rarely" about his time on HMS Quentin.

"On one occasion, he simply said, 'It was a bit grim', and I could tell he didn't really want to say anymore."

Mr Kirkham admitted it was "quite emotional" reading the innermost thoughts of his father as a young man, uncertain of his survival.

The diary of "a mild-mannered and courteous man", Mr Kirkham said it had "very much" helped him mourn his father.

"I can hear his voice saying a lot of these things and that's nice."

Mr Kirkham said the diary also served to put the rest of his father's life "into some kind of context".

Nothing could have been as bad as "being on a destroyer, not knowing if you are about to be bombed or sunk", he said.

However, he added: "I can't ask him, 'What do you mean here, Dad?' which is a bit sad really."

Follow BBC Yorkshire on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].