Christian Cole: Oxford University's first black student

Bodleian Library

Bodleian LibraryIn a salute to a "remarkable" man, the University of Oxford has paid tribute to its first black student. But who was Christian Cole and what was life like for him at a time when being black at the university wasn't merely unusual, but remarkable?

Cole was always likely to turn heads when he arrived in Oxford to read classics.

It was 1873 and he was a 21-year-old black man from Waterloo, Sierra Leone, studying alongside young men from the elite families of Victorian England (His arrival pre-dated the institution of the university's first women's college by six years.).

The city must have appeared a daunting place for Cole, said Dr Robin Darwall-Smith, an archivist at University College Oxford.

"For a lot of people he would have been the first black African they had ever encountered," he said.

University College

University CollegeEven understanding his colleagues might have initially been a challenge for a man used to hearing English in a Sierra Leonean dialect, according to cultural historian Pamela Roberts.

The author of Black Oxford: The Untold Stories of Oxford University's Black Scholars, she said he could have expected no special treatment.

"This was not a time of affirmative action or quotas," she said.

Little is known about Cole's early life in Africa, but Ms Roberts suggests a good education and his impressive intellect would have stood him in good stead.

Cole was the grandson of a slave and the adopted son of a Church of England minister in Sierra Leone.

He had studied at Fourah Bay College in the country's capital, Freetown. It was established by Christian missionaries in 1827 and was known as the "Athens of West Africa" because of its academic reputation.

TargetOxbridge

TargetOxbridgeCole was a non-collegiate student at Oxford - to help poorer students who might not be able to afford college fees, it was possible to study without being part of a college at the time.

He received an allowance from his uncle to support him, which he supplemented by tutoring and giving music lessons.

These extra commitments did not prevent Cole from making an impression on Oxford life, said Dr Darwall-Smith.

He spoke at the university's debating society, the Oxford Union, and seems to have been a well-known figure.

When he attended Encaenia, Oxford's honorary degree-giving ceremony and a great social occasion, his presence did not go unnoticed. The Oxford Chronicle recorded there were "three cheers for Christian Cole" before the event.

"There would have been these visitors saying, 'gosh, who is that?' 'That is Christian Cole, he's from Sierra Leone.' 'Wow, gosh, how exotic'," Dr Darwall-Smith said.

"Cole would have known this... but he went along. I admire him for that," he added.

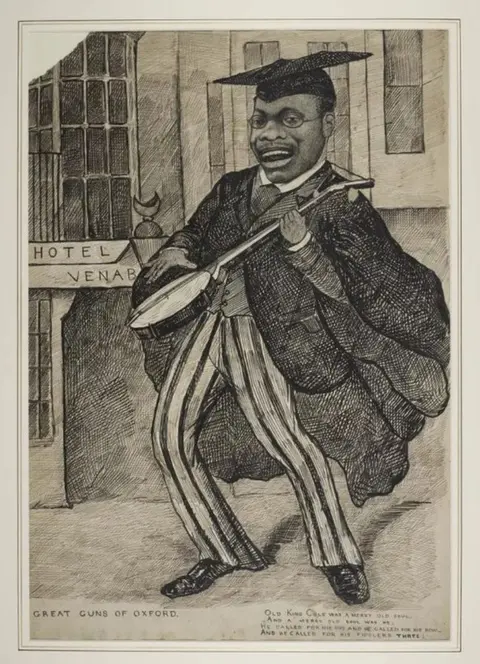

His presence in Oxford was also documented in cartoons and he is mentioned in the diary of Anna Florence Ward, who describes spotting him on a visit to her brother, who was at Magdalen College, in June 1876.

She wrote: "Saw Christian Cole (Coal?) also" and then used the N-word in brackets.

Master and Fellows of University College

Master and Fellows of University CollegeAlthough to modern eyes the diary entry is clearly racist, Dr Darwall-Smith said he felt Cole's contemporaries were "looking out for him".

He cites as an example an appeal started by students to help Cole financially after his uncle died.

It was supported by the master of University College George Bradley and fellow student Herbert Gladstone, the son of four-time prime minister William Ewart Gladstone.

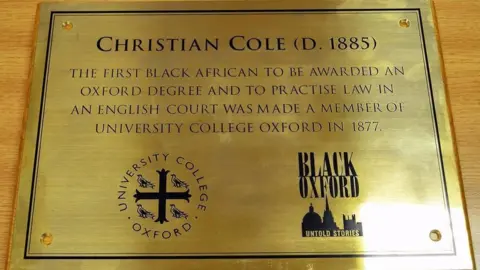

Bradley went on to award Cole membership of University College after he left with his Oxford degree in 1876, and paid his college membership fee for two years.

Cole graduated with a fourth-class honours degree in classics, although Dr Darwall-Smith stressed that this was no failure.

Teaching for non-collegiate students was not as comprehensive and very few students who did not belong to a college achieved honours degrees in this period.

Classics was also considered to be the toughest subject at the time.

After leaving Oxford, Cole returned to Sierra Leone before coming back to England to join the Inner Temple in London, prior to becoming the first black African to practise law in an English court, in 1883.

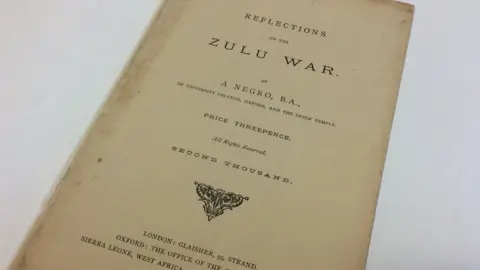

He also published a poem attacking British policy in the Zulu War under the name of a "A Negro, B.A., of University College", in 1879.

The text was addressed to WE Gladstone MP, who he describes as his "Master and Father in politics".

Despite his achievements and his status as the university's first black student, Cole's name is not widely known - although that could be something that will one day change.

The university has said it is a "priority" to broaden the range of people represented by pictures, paintings and plaques around its buildings.

OxfordACS

OxfordACSIt is part of a wider recognition the public perception of Oxford University is that it is a place for wealthy, mostly white, students, something that can deter black and ethnic minority candidates from applying.

It is a problem Tobi Thomas recognises. She was the only black undergraduate in her year at Trinity College when she arrived last September.

"There are films like The Riot Club [a depiction of a hedonistic, all-male Oxford University dining society]... I remember talking to friends who said why are you applying?" she said.

Naomi Kellman runs Target Oxbridge, a programme set up to support black students applying to Oxford and Cambridge. She said these narratives can have a "really big impact", which is why they introduce potential applicants to black students at Oxford in order to have those "myths busted".

But how did the story end for the pioneering Christian Cole?

Sadly, it appears he struggled to find enough work after becoming a barrister and he moved on to East Africa.

Information about his life there is "very, very patchy", said Ms Roberts.

Cole died in 1885 in Zanzibar of smallpox aged 33.

At a plaque unveiling held on Saturday, and timed to coincide with Black History Month, the master of University College Sir Ivor Crewe paid tribute to Cole's "remarkable achievements", and said he hoped the plaque would be "a symbol of our continued commitment to recognising and supporting the brightest students whatever their backgrounds".