Staff shortages in care industry: 'It takes a strong person to do this job'

Martin Giles/BBC

Martin Giles/BBCSenior figures in the care industry have warned the sector is in crisis because of staffing shortages. What are the issues and what is it like working in a care home?

Across Norfolk, there are currently 210 people in hospital who should be in a care setting.

Of those 210, 120 people need home care and the remaining 90 require care home beds.

The problem they, and those responsible for their welfare face, is a dire shortage of available care.

It is thought between 8% and 10% of the county's care staff are currently either isolating or poorly with Covid. That is on top of a profession already struggling both to retain existing workers and recruit new ones.

The BBC visited Norfolk Lodge in Hunstanton, which is home to 25 residents.

It has the space to offer more residents a home. What it does not have is the staff to ensure extra residents can be properly looked after.

The home is one of a number of care settings trying to recruit people from countries such as India and Nigeria.

'Staffing is the most important thing'

Leah Guy is the home's manager.

Staff shortages, she says, has meant workers - including herself - are often putting in 14-hour days to cover the gaps.

"If this continues, there will be issues," she says, adding the system is currently surviving on goodwill.

"We are not getting any staff locally, they just don't want to do the work.

"It is difficult times at the moment."

The home currently has two bedrooms spare.

"If we had enough staff then we would be able to get more residents in. At the moment, we are a bit restricted until we have more staff," she says.

"Staffing is the most important thing at the moment.

"We need people to be coming in [to the care sector]. And it is not going to change because of the pay.

"At the end of the day, no matter how much you love your job, you need money to survive and with prices going up and everything else it is difficult.

"It was getting worse before Covid."

Ms Guy says the status of care work needs to change.

"It takes a strong person to do this job," she says. "And once care gets seen as a professional job then we will get more people wanting to do it."

'It makes my day wonderful'

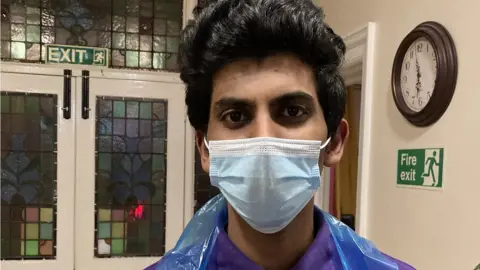

One of those who has recently joined the care sector is Nijo Kanakan, who is originally from India.

He was studying tourism management in Brighton when the pandemic started.

As the outbreak continued he began having doubts about whether his course was worthwhile and applied for care sector work after seeing an advert.

You might also be interested in:

Having cared for his grandfather back home in India, he was initially only looking for part time work.

He is now senior care assistant at the home.

"I wanted to see how it is and when I started the training I [found] it was quite good. Their [residents'] happiness makes me happy. It makes my day wonderful.

"I think I can have a big career in this field."

He says he believes the compulsory Covid vaccination for care staff has put some people off working in the sector.

Pay might be a factor for some people, he says, but he says he is less concerned with the pay he gets than the sense of fulfilment his role brings.

'The work is a lot harder than people think it is'

Carer Marilyn Clarke has worked at the home for eight years.

That work, the 68-year-old says, has become increasingly challenging.

"Mentally and physically [the work] has got a lot harder," she says.

"Now, as people are living longer, and dementia sets in - the majority of people here have dementia - it can be quite challenging sometimes.

"A lot of staff come in and think it is residential [care] and the work is a lot harder than people think it is."

This, she says, is reflected across the care sector.

She says bringing younger people into the sector is difficult, not least because much of the job is not what people expect.

"It can be very messy, in more ways than one," she says. "A lot of youngsters don't want to do and the money is just basic. If you're a young man with a family, for example, it is not a living wage."

She tells how a friend in the sector retired because she was better off financially in retirement than working in a care home.

"Part of me feels I want to carry on because I can and I don't want to admit to getting old," she says.

"Most of the time it is rewarding."

'It is like a second family'

Activity coordinator Bronwyn Goodrun used to work as a holiday home cleaner in the area.

"What brought me here is I really wanted to get into the care side of a job," she says.

"This is what came up, I heard back straight away and here we are.

"It is a really good sector to be in. I like spending time with all the residents and getting to know them and obviously trying to help them when they need help.

"It is definitely like a second family which is always welcome and open."

Analysis: Nikki Fox, BBC East health correspondent

The reason why the health and social care system in Norfolk and Waveney has been on what's called "Critical Incident" is largely down to staffing shortages in social care.

Seventeen per cent of the 1,000 beds at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital are taken up by people who are medically fit and can't be discharged.

Omicron has exacerbated absences but things have been getting progressively worse since Brexit.

Some care homes don't want to take more patients because they're worried the standard of care will decrease. These homes rely on a decent rating by the watchdog - the Care Quality Commission - to attract private residents.

Norfolk County Council says it has written to care homes offering enough to provide a 6% pay increase to staff both now and in the 12 months from April. But they're not confident every home will take them up on the offer because they might have to shoulder the increase themselves after the subsidy finishes in 2023.

Because there aren't enough care home beds, some people are now being sent to hospices instead.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. If you have a story suggestion email [email protected]