Great Yarmouth: How offshore wind is re-energising seaside town

great-yarmouth.co.uk

great-yarmouth.co.ukIn the past decade the UK has emerged as a world leader in offshore wind energy. And some of the biggest winners from the multi-billion pound investment look set to be coastal towns searching for their industries of the future.

On a clear day, the tourists walking Great Yarmouth's beachfront Golden Mile can see the turbines of the Scroby Sands wind farm spinning in the distance.

Onshore are the attractions and arcades that have sustained this Norfolk seaside resort for the past half-century; far offshore stand the huge structures on which rest its hopes for the next.

Twice the height of Big Ben and with blades longer than a jumbo jet wingspan, the new turbines being built many miles into the North Sea will dwarf the 15-year-old wind farm visible from the beach.

At full capacity, the planned projects could power the equivalent of 4.5 million homes, but the multi-billion pound investments are already having an energising effect on the local economy.

Having seen the decline of its fishing industry and ridden the ups and downs of the oil and gas industry, Great Yarmouth and its neighbouring port Lowestoft find themselves at the centre of the UK's renewables boom.

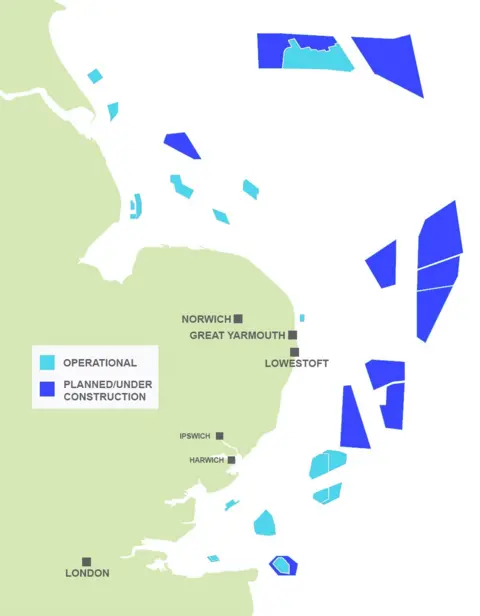

The UK already has offshore wind turbine infrastructure that could provide a capacity of 7.5GW - more than any other country in the world - and more than half of it is off the coast of Norfolk and Suffolk.

A combination of shallow waters, consistent wind and good access to the energy-hungry south-east England has already attracted projects costing £11bn, with projects worth £22bn - and more than 6,000 jobs - planned by developers into the next decade.

In March, the government laid out in an industry sector deal its ambition for 30% of electricity to come from offshore wind by 2030, and the falling cost of renewables has fuelled ambitions of the UK being carbon zero by 2050.

It all adds up to an unmissable opportunity, says Simon Gray of industry body the East of England Energy Group.

Coastal Britain

These stories are part of special coverage across BBC News looking at the challenges and opportunities in Britain's coastal towns.

"The great thing about this is that the wind farms are set to last 20, 30, 40 years. It means two generations of a workforce that will be operating and maintaining these turbines," he said.

"We are developing these skills and will be exporting them around the world," he says.

great-yarmouth.co.uk

great-yarmouth.co.ukWhile much of the manufacturing is done further up the east coast or abroad - which has drawn criticism - construction and maintenance is creating work for local companies.

Great Yarmouth's port is being used as the construction base for ScottishPower Renewables' £2.5bn East Anglia One wind farm, due for completion next year.

But an even bigger prize is the operations and maintenance deal it has secured for Swedish energy firm Vattenfall's two wind farms, which will be the biggest in the world.

They will bring up to 150 jobs for 25 years, and create hundreds more in the supply chain.

Yarmouth firm Subsea Protection Systems makes protection for undersea cables, and says it could double its 50-strong workforce if it wins a contract on the projects.

And Peel Ports has invested £12m in Great Yarmouth port to attract bases for future wind farms. It has been working with local councils and the region's local enterprise partnership.

"This is our opportunity," says port director Richard Goffin. "We've been saying this for two years but the government have now put their flag in the ground and said they want us to do it."

'Manna from heaven'

Former fabrication engineer Gwyn Evans has retrained as an offshore wind technician thanks to a course run by a local engineering firm.

Accustomed to the peaks and troughs of seasonal work, he had been out of work for six months and saw the writing on the wall.

The opportunity to train for free with Great Yarmouth-based 3Sun was "manna from heaven", he says.

The company offers the training as a way to recruit new talent into its growing offshore wind work.

"Things are standing a lot better in my favour than they were," says Mr Evans, 38.

"Now I have the [qualification] tickets the world is my oyster. I can earn a decent wage and improve my lifestyle.

"Everybody wants a job that's going to last. If you are lucky enough to be in an industry that you are passionate about and love, that's even better."

The opening of a new £557m government subsidy round is likely to attract more private-sector investment.

But infrastructure projects on such a scale inevitably attract opposition.

The huge cables needed to transfer the power from the wind farm to the grid require vast swathes of the countryside to be dug up.

For example, Vattenfall's proposed wind farms require 37 miles (60km) of cabling to be laid underground to a substation at Necton in Norfolk, which residents say will blot the landscape and cause huge disruption.

The company insists it is working with residents to find the best solution and the project will bring significant environmental and economic benefits.

PA

PAMid Norfolk MP George Freeman has raised the wider issue in Parliament, warning that community voices are not being heard in a planning "free-for-all".

Critics also ask why infrastructure cannot be better planned and shared - a concern the government has pledged to investigate in its sector deal.

That launch has focused attention on the future. At 5,000-student East Coast College, where a new £11m energy training centre is being built, they can feel the change in the air.

The sector deal "felt like firing a starting gun" says chief executive Stuart Rimmer. He believes the prospect of well-paid, long-term jobs on their doorstep is creating real excitement among students.

"Aspiration follows opportunity," he says. "We have to explain they are not just getting a qualification, they are getting a future."