Lucy Letby: How could the NHS stop a future killer within?

BBC

BBCNearly a quarter of a century before Lucy Letby began attacking babies on a neonatal unit, another hospital experienced similarly sudden and unexpected losses.

Deaths on the children's ward at Grantham and Kesteven General Hospital in Lincolnshire were rare until a two-month spell in the spring of 1991, when four babies and children died suddenly and nine others collapsed, some repeatedly.

Five-month-old Paul Crampton mysteriously collapsed three times before going on to make a swift recovery on each occasion. No-one was able to explain what had happened.

"It's very scary," remembers his father, David Crampton. "A child ill and no-one - the people who are meant to know - can tell you why."

Paul had been in hospital with a chest infection and had been due to go home the day before his first collapse.

He was transferred to another hospital, where he made a full recovery and was discharged.

david crampton

david cramptonA few days later, police contacted Mr Crampton and broke the news that Paul's sudden deterioration had probably been caused by him being given drugs.

A criminal investigation was launched.

In the following days, he and other affected families began to realise the full truth.

"We knew there had been collapses across Grantham hospital at that time," said Mr Crampton. "We were clear that this was going to become a much bigger story. We didn't know how big."

It would be two more years until Beverley Allitt, a nurse in the hospital's paediatrics ward, was convicted of killing four children, attempting to kill three more - including Paul - and grievous bodily harm against six others.

After her trial, Mr Crampton stood on the steps with other victims' families outside Nottingham Crown Court and called for an inquiry into what had happened.

"What I felt these crimes of Allitt showed was the inability of the health service to respond to a developing crisis and put forward a course of action to understand what was happening and prevent it from going any further," he exclusively told BBC North West Tonight.

An independent inquiry was held immediately after the trial, chaired by Sir Cecil Clothier.

While his report, published in 1994, identified a number of key failings it essentially found that because each individual collapse and death could be explained away - and no-one could believe that a colleague would deliberately harm babies - Allitt was able to continue for more than two months.

The parallels with Letby are striking.

While some senior colleagues did raise concerns about her after the first few months, others - including those in charge - were apparently unable to contemplate that there may be a killer in their midst.

In this way, she was able to continue her attacks for a year.

PA Media

PA MediaSo what, if anything, could have stopped Letby sooner? And what lessons can be learned?

Bill Kirkup has chaired several high-profile NHS inquiries, including examining baby deaths at the Morecambe Bay and East Kent hospital trusts.

While it is important to stress that none of his investigations involved examining the deliberate harming of babies, Dr Kirkup identified a common feature in organisations when things start to go wrong.

He expressed concerns about how people react to signs of problems, how it goes on for too long before it is picked up, and how the response is very often inadequate.

"Vigilance, thinking the unthinkable, it's very difficult to do," said Dr Kirkup, who wants to see better systems for tracking patient outcomes put in place.

For example, if an unusual number of deaths are entered on to that system, it would trigger an automatic flag for a particular course of action.

In this way, human bias - the automatic and understandable assumption that your friends and colleagues are not acting malevolently - would be less likely to be a factor in management decision-making.

Dr Kirkup explained: "We don't look at individual variation in particular units in any systematic way and if we tracked these things in real time, it's been shown in other specialities you can do this, you can trigger action.

"You can say: 'There's something untoward happening here, it's outside the limits of normal variation - we need to look at it'."

In other words, a stronger system of checks and balances.

For years, Dr Kirkup has also been calling for medical examiners - independent senior doctors who look at all deaths which are not seen by a coroner.

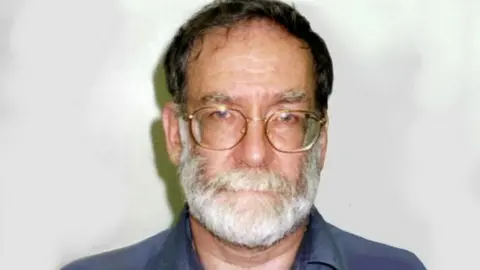

It was recommended by the public inquiry into Dr Harold Shipman - the Greater Manchester GP who is thought to have killed 250 of his patients.

GMP

GMPTwenty years after that recommendation was made, medical examiners are finally being introduced.

In 2015 - the year when Letby began to attack babies in her care in the Countess of Chester's neonatal unit - Dr Kirkup publicly lambasted the government for having failed to introduce medical examiners.

While he welcomes their introduction, he very much regrets the delay.

When asked whether it could have made a difference in Letby's case, he said: "I think if somebody had asked difficult questions around the nature of the events - the pattern of events that were difficult to explain - at least somebody would have had to look harder.

"It's entirely possible that at some point what should have happened would have happened [and] somebody would have said 'There is something very wrong here'."

There are other parallels between Allitt and Letby.

Allitt was eventually caught because Paul Crampton's blood sample showed an exceptionally high level of artificial insulin.

Letby also poisoned two babies with insulin who would go on to recover.

Other killers have used this technique.

In May 2015, health worker Victorino Chua was convicted of murdering two patients and poisoning several others with insulin at Stepping Hill Hospital in Stockport.

Despite the deaths occurring only 40 miles away from Chester - and Chua's trial receiving much media attention both locally and nationally - nobody working at the Countess of Chester at the time appears to have spotted any possible parallels.

PA/Elizabeth Cook

PA/Elizabeth CookWhen the blood results for both babies came back the high insulin levels did not trigger any major investigation into what had happened.

If it is part of the human condition to try to rationalise away unexplained and shocking events, what can be done?

"I think Beverly Allitt did change perceptions amongst clinicians and made the unthinkable slightly less unthinkable," said Dr Kirkup. "Not necessarily an awful lot, as I think we've seen here, but a bit less."

Mr Crampton said that he did not dwell on what might have happened to Paul - who is now a dad himself -and stressed his support for the NHS.

"It is something we need to value and treasure as a society. We all need it at some point in our life," he said

But he added that while cases like Allitt's were extremely rare, he also thought it was important to see a meaningful change in the way concerns were addressed.

"I am absolutely sure that there are more safeguards than there were in the days of Allitt but I still don't think that fundamental question of once you have an issue - and staff start to suspect that there's an issue - how does that get elevated?

"Fundamentally, something's got to change hasn't it? We can't allow these things to continue".

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram? You can also send story ideas to [email protected]