A glimpse into the future: Carbon capture in Kensington

BBC

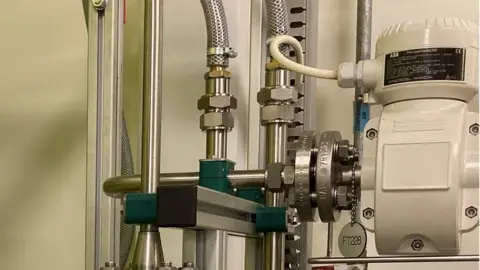

BBCInside a four-storey building, a futuristic air is created by shiny pipes and digital dials. It looks like the interior of a spaceship - so hi-tech that film companies have scouted the location for their productions.

This is a carbon capture facility and it is in Kensington in London at Imperial College.

It is the only plant of its type in the world - thousands of students from across the globe are taught about carbon capture.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is an emerging industry that takes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, turns it into a liquid and then stores it underground in places like the North Sea.

Scientists say carbon dioxide comes partly from burning fossil fuels and contributes to our warming climate.

No-one thinks CCS is a silver bullet to reducing carbon dioxide. The process is expensive. It uses a lot of energy to run. Environmentalists say carbon capture is overhyped and will delay the phase-out of fossil fuels. That we should be focusing on reducing emissions and reducing the burning of fossil fuels.

Carbon capture advocates, though, say it will be part of any solution in reducing emissions.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said that if we are to limit global temperature increases to 1.5C we need to deploy the technologies that can remove carbon.

Dr Colin Hale runs the plant at Imperial: "If you look at any of the 10-point plans for any of the emerging economies, renewables has got a significant part to play, nuclear has a part to play.

"In some of those economies, being more sustainable has a part to play. Carbon capture is essential for us to achieve those net-zero goals and the reason for that is there's some industrial processes for things that we use day to day - like concrete or cement - that are very, very difficult to decarbonise in other ways so carbon capture is quite key to those."

The students here come from all over the world. One of them, Jaace Chern, said: "Definitely this kind of technology is interesting. I'm from Malaysia and basically this technology is just emerging from Malaysia. So having the chance of working in this plant gives me first-hand experience of working in it."

Amy Mcloughlin, who is from Ireland, said: "I think a big challenge for the future is how to store the CO2. I'm quite excited to learn more about that. I have two more years left and I'm very interested in finding out more about that."

Recently Claire Coutinho, the Energy Secretary, said the government was planning to invest billions in carbon capture technology: "These announcements put us on track to achieve between 20 and 30 million tonnes of captured and stored carbon dioxide a year - the equivalent of taking four and six million cars off the road each year from 2030.

"If we make this target, it will support 50,000 jobs by 2030, and add £5bn to the economy by 2050, not only helping us deliver our net-zero commitments - but also creating prosperity throughout the UK."

At Imperial, they want to prepare their students for this emerging sector.

Dr Hale said: "One of the key drivers for us when we developed it initially was around ensuring that our students had the skillsets that they're likely to need to be able to participate - but more importantly develop that energy transition because they're going to be key to enabling us as nations to achieve our net-zero obligations."

Simon Wynne is head of energy industries in the UK and Ireland at ABB, which supplies the components to the Imperial site: "Will it work? Yes. That's part of this. This is a real plant that operates.

"For the last 11 years [we have been] running that process and demonstrating that the process works and educating students how to manage and control that process.

"Is it part of a wider range of measures we need to cut emissions? Absolutely."