Battersea Power Station opens after decades of decay

BRENDAN BELL

BRENDAN BELLLooming over the River Thames, Battersea Power Station lay derelict for decades. On Friday, though, the reinvention of one of London's truly iconic buildings is complete as it opens to the public for the first time.

Transforming this beloved Art Deco edifice into a shopping and leisure complex has been a "Herculean" task, says Simon Murphy, boss of the Battersea Power Station Development Company (BPSDC).

During a 10-year project, the four famous white chimneys towering over the Thames have been dismantled and rebuilt, due to the corrosion of their steel structures.

The power station's distinctive brickwork has, where necessary, been meticulously recreated. Two firms that made bricks for the original buildings were called on to supply 1.75 million matching replacements.

The roof of the building, in Nine Elms in the borough of Wandsworth, also had to be replaced. It was removed by a previous owner as part of a doomed project to turn the power station into a theme park.

More than three times the quantity of steel used to construct the Eiffel Tower has been used in the rebuild, the developers say.

BACKDROP PRODUCTIONS

BACKDROP PRODUCTIONS BACKDROP PRODUCTIONS

BACKDROP PRODUCTIONS"Throughout the restoration process, we have tried to reuse as much of the existing fabric within the power station as possible," Mr Murphy says.

He describes the redevelopment as "one of the most challenging engineering and architectural feats in London's history".

The project has, perhaps unsurprisingly, not been met with universal acclaim.

One prominent campaigner says the power station has not been treated with the "respect it deserves", while the Labour group on Wandsworth Council has turned down an invitation to attend Friday's opening over its concerns about the number of affordable homes being built during the wider redevelopment of the area.

James Parsons

James ParsonsFor Mr Murphy though, Battersea Power Station is now a "destination", where people can live, work, shop and play.

Visitors can pay to travel 357ft (109m) up the north-west chimney in a glass lift, emerging on to a 360-degree viewing platform.

They can shop or dine in one of the restored turbine halls, which span over three levels. The halls are lined with more than 100 retail units and eateries.

Turbine Hall A, built in the 1930s, is the place to go for premium fashion collections, BPSDC says. Turbine Hall B, meanwhile, a relic of 1950s brutalism, promises an "eclectic" mix of contemporary brands.

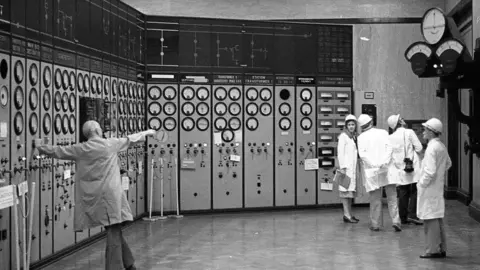

It is also where Control Room B is to be found - a hip hangout promising "electrifying cocktails in a historic setting".

The original Art Deco Control Room A, the first to be built and once key to sending coal-fired power across large swathes of the capital, is now an events space.

Monty Fresco

Monty FrescoHere, a semi-circular control desk and two long banks of switchboards have been painstakingly preserved. Teak parquet flooring, Italian marble tiling and a gold-painted ceiling present visitors with a "one-of-a-kind" experience, BPSDC says.

The power station's Boiler House is to become Apple's new London headquarters, the workplace for more than 1,000 staff.

Sitting above the Boiler House is the "jewel in the crown" of the development - 18 "Sky Villas" - luxury flats nestled among roof terraces and gardens. They are among 254 flats making up the residential offering here.

WilkisnonEyre

WilkisnonEyreAnd there is more - a new pedestrianised high street next to the power station, Electric Boulevard, which will welcome its first shoppers on Friday.

At the heart of the transformation was the ambition to retain the "old industrial feel to the building", says Sebastien Ricard, the project manager for architects WilkinsonEyre.

Preserving its history is "what gave us a big buzz", he says.

Ian Lidell

Ian LidellHaving taken on the project in 2013, Mr Ricard's team was faced with a contaminated roofless shell with crumbling walls.

The power station is three times the size of the Tate Modern, he says, underlining the scale of the project.

"That's the fascinating challenge for us as architects - dealing with that amazing structure, wanting to retain the sense of scale, the sense of history and industrial history and at the same time to make sure we were creating some pockets of space within the building which make you feel comfortable if you're going to live there, if you're going to work there, or shop there."

BPSDC

BPSDCBuilt by the London Power Company from 1929, the power station consisted of two identical sections, each with two tall white chimneys.

During the early stages of World War Two, RAF pilots are said to have relied on the power station's plumes of smoke to guide them home in the mist.

At its peak, it supplied power to a fifth of London, including Buckingham Palace and the Houses of Parliament.

Decommissioned in 1983, Battersea Power Station lay abandoned and decaying for some 30 years.

John Stillwell

John StillwellToday, the 42-acre site is part of a vast £9bn commercial and residential development.

In the years following its acquisition by Malaysian investors in 2012, several shiny tower blocks sprung up and along came cocktail bars, coffee shops and cafes.

As a consequence, Battersea Power Station itself is obscured and can only be easily seen from the riverside.

Keith Garner, a founding member of the Battersea Power Station Community Group, believes this "sublime, awesome, thrilling" landmark has not been treated with the "respect it deserves".

"That wonderful experience of seeing that building, the thrill of seeing the building has gone, gone forever, which is tragic," he says.

"It's no longer a landmark if you surround it with other massive buildings."

It's "astonishing" this has been allowed, he says, adding that lottery grants should have been awarded to enable the power station to be turned into a cultural or sporting venue.

It has taken "40 years to create a shopping mall", is Mr Garner's verdict.

WilkinsonEyre

WilkinsonEyre Reuters

ReutersAccording to Historic England, the commercial offering is "part of a planning balance".

The body, which worked on the renovation, listed the building in 1980, setting stringent rules for future development. It is possible that without that protection, Battersea Power Station might have been demolished.

"It's easy to be critical, but we see this as a fantastic regeneration which does put heritage at its heart," says Alasdair Young, a historic buildings inspector on the development.

Bringing old industrial buildings back into use is "challenging", he says. "A lot of money needs to be invested to give them [old buildings] a future."

According to BPSDC, at one point £2m a day was being spent on the renovation.

WilkinsonEyre

WilkinsonEyreOver the next decade, more new homes, shops, restaurants, leisure venues and offices will spring up nearby, under BPSDC's plans.

But all of this could yet come up against opposition in the form of Wandsworth's recently elected Labour council.

The administration's biggest complaint is that out of 4,000 new homes planned, only 9% will be affordable, under permissions negotiated with the former administration.

Of the homes built so far, 20% are affordable, BPSDC says, and a "mechanism has been agreed" with Wandsworth Council to look at the "possibility for more affordable homes to be delivered in the future".

For Mr Garner, himself an architect, the handing of the site to the private sector was a mistake.

"What they have done is spiritually desolate."

Follow BBC London on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]