Louis Wain: The artist who changed how we think about cats

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the Mind"He had made the cat his own. He invented a cat style, a cat society, a whole cat world. English cats that do not look and live like Louis Wain cats are ashamed of themselves."

So proclaimed the science-fiction writer HG Wells about the phenomenon that was Louis Wain - an illustrator who at the start of the 20th Century was a household name credited with changing people's feelings about felines.

Yet Wain's life was scarred by tragedy. His wife, who inspired the drawings that turned him into a national treasure, died days after the first of his cat pictures was published. Wain's inability to profit from his successes, and his failing mental health, led him to poverty and a pauper asylum.

He was rescued from his gruesome surroundings thanks to a campaign which even the prime minister of the day supported. In his new home at London's Bethlem Hospital, the artist decorated the building for Christmas in his own unique style.

Wain's fame was not enduring, although a new film starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Claire Foy, The Electrical Life of Louis Wain, is set to thrust his story into the limelight.

Who was the man behind the cats?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBorn in Clerkenwell on 5 August 1860, Louis Wain would find work as a teacher at the West London School of Art, where he had also been a student. He went on to become a freelance artist for trade journals and newspapers.

"He made his living producing engravings that would be published in publications such as the Illustrated London News at a time when they could not reproduce photographs," explains Colin Gale, director of the Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

Wain's talent shone through in the various subjects he tackled and he was rarely short of work. Yet it was a family tragedy that led to him becoming famous.

2021 STUDIOCANAL SAS–CHANNEL FOUR

2021 STUDIOCANAL SAS–CHANNEL FOURAt the age of 23, he married his sisters' governess, Emily Richardson, but soon after she was diagnosed with terminal breast cancer.

"In the last years of her life they had a family pet, a cat by the name of Peter, and to amuse her he would do caricatures, just privately - they weren't for publication," says Mr Gale.

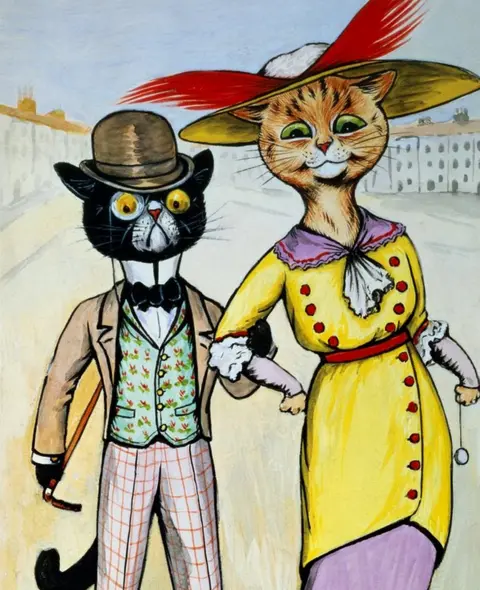

But after seeing the drawings, editors at the Illustrated London News, where Wain was a freelancer, offered to print some of his cat art. Days before Richardson's death, A Kitten's Christmas Party - a drawing featuring 150 cats that took 11 days to create - appeared in the newspaper.

"They became an overnight sensation," says Mr Gale. "People loved his pictures of cats because they weren't simply of cats; they were of cats doing things which humans did."

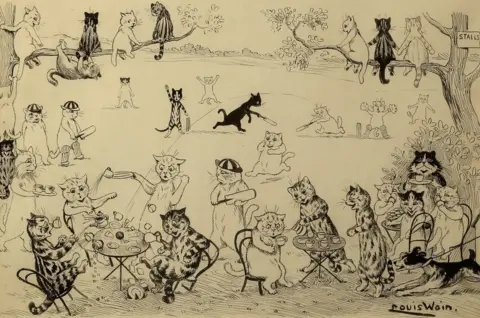

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the MindThere were cats playing cricket, cats digging up roads, cats riding bicycles.

Often these were created as Wain sat in public places and furtively sketched the people around him, but as anthropomorphised felines.

"Very often the drawings were there to poke fun at the way people behaved. He also did a few political satirical cartoons, so Winston Churchill as a cat, but it was all very gentle," the museum director says.

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the MindMerchandise such as Christmas annuals and postcards further spread his fame and Wain became known simply as "the man who drew cats".

In his 1968 biography of the illustrator, Rodney Dale wrote that Wain's images had such an impact that "the attitude of the general public towards cats, and their feeling for cats, was greatly affected".

Yet in spite of such success money was always a problem, as Mr Gale explains.

"He was never that good in business. He didn't enforce copyright for instance, so he ended up quite poor, which is why he ended up in Springfield Hospital."

Historical Picture Archive/Getty Images

Historical Picture Archive/Getty ImagesThe mental health of Wain, who had always been considered eccentric, deteriorated as he got older. He became increasingly verbally abusive and violent towards his sisters, with whom he lived.

In June 1924, at the age of 63, he was certified insane and taken to the paupers' ward of the hospital in Tooting, south London.

His discovery there by a journalist a year later led to a high-profile campaign to find him better care.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPrime Minister Ramsay MacDonald was among those who backed the campaign - he would even go on to arrange for Wain's sisters to receive a small Civil List pension to recognise their brother's services to art.

HG Wells took to the radio in support of the illustrator, and before long enough money had been raised to move Wain to the more comfortable surroundings of Bethlem Hospital, then located at Southwark in south London. It is, of course, the institution from which we get the word "bedlam".

"Stigma [about mental disorders] certainly did exist 100 years ago," Mr Gale says. "I've been an archivist long enough to know that some people looking at their family history are discovering ancestors who were placed in psychiatric hospitals and it had been kept a family secret.

"But in relation to Louis Wain, there was such a public affection for him that I suppose whatever condition he had - there's a certain amount of uncertainty about that - people just wanted to see him properly cared for."

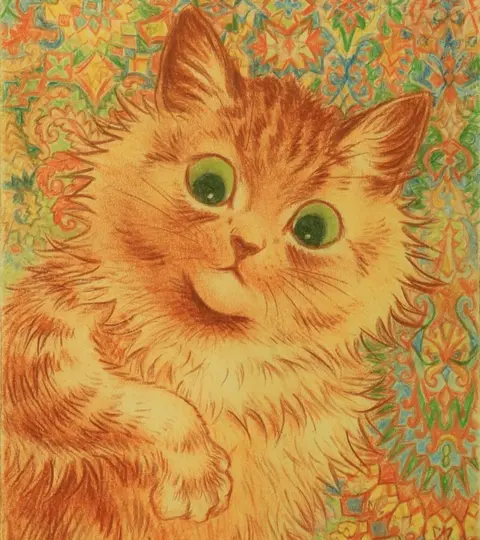

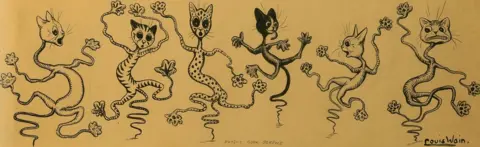

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the Mind Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the MindAt Bethlem, Wain was found by staff to be a quiet and co-operative patient. His treatment was centred on making his environment as pleasant as possible.

"He was freed from those financial concerns then and just did it for love, and the hospital recognised that and gave him everything he needed to continue," explains Mr Gale.

BBC

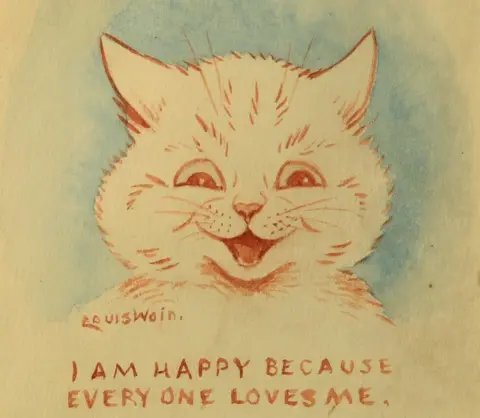

BBCOne Christmas, hospital staff asked if he would like to help decorate the building. Wain decided to use the mirrors there as his canvas.

Cats taking part in various Christmas-time activities began appearing on the walls of the hospital.

These creations form part of a Wain exhibition at the Bethlem Museum of the Mind, which is on the site of the working psychiatric hospital.

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the Mind Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the Mind Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the MindWain left Bethlem Hospital in 1930 when the institution was moved to its present location in Beckenham, south-east London.

He was transferred to Napsbury Hospital, near St Albans, where he would continue drawing until his death in July 1939.

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the MindFor Mr Gale, the exhibition and film are not only a way to bring Wain back into the public consciousness but also to help promote a better understanding of mental health.

"I suppose people might think 'mental distress, disorder - gosh the artworks must all be very dark', or else they might think 'creativity and madness, isn't that linked, isn't that what drives art?'.

"Louis Wain is a great example of saying all that is just nonsense. Yes he was unwell in later life and in care, but actually painting was just part and parcel of who he was and what he did.

"The works just exude pure joy and mischievousness and fun."

Bethlem Hospital

The world's oldest psychiatric institution

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the Mind- Founded near Bishopsgate in central London in 1247 as a priory of the Church of St Mary of Bethlehem to serve knights setting off for the Crusades

- Referred to as a hospital by 1329; there is evidence of Bethlem being used to house the insane from 1403

- Moved in the second half of the 17th Century to nearby Moorfields, where until 1770 sightseers were able to gaze at patients in the institution's two galleries

- Relocated south of the River Thames in 1815 to a building which now houses the Imperial War Museum, before being moved to its current site in 1930

- Bethlem Royal Hospital continues to provide care as part of the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust

Bethlem Museum of the Mind

Bethlem Museum of the MindAnimal Therapy: The Cats of Louis Wain runs at the Bethlem Museum of the Mind - which is based in the hospital's former administration wing - until 13 April.

The Electrical Life of Louis Wain opens in UK cinemas on New Year's Day.

All images subject to copyright