Muriel Gardiner: The heiress who saved countless lives

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum London

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum LondonMuriel Gardiner's interest in the work of Sigmund Freud took her to Vienna in the 1920s to study medicine. There, the wealthy American became part of the underground resistance in the fight against fascism, helping to save countless lives. Her courageous actions would help to inspire a film for which Vanessa Redgrave won an Oscar. What were the events that shaped this extraordinary life?

Early one November morning in a hotel room in Nazi-annexed Austria, Muriel Gardiner was woken by a sharp knock on the door.

Opening it, she found a Gestapo officer demanding to know what she was doing in the country. With her heart beating wildly, the medical graduate politely told him she had been visiting the city of Linz as a tourist. More questions followed but the officer finally left.

Had he investigated further, he might have learned that Gardiner was not who she claimed to be.

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum London

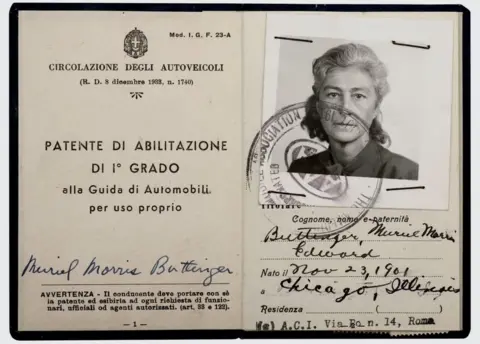

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum LondonGardiner was born in Chicago in 1901 into the Morris family, which had become hugely wealthy through the meatpacking industry.

"From a very early age she felt it was very unfair that she had such wealth and she recognised that other people didn't," explains Carol Seigel, director of the Freud Museum London, which is holding an exhibition about its "founding mother" Gardiner.

"She became quite interested in politics. Even when she was quite young she organised a kind of women's suffrage march."

Gardiner's views had been forged in part by one of the 20th Century's most famous events - the sinking of the Titanic in 1912.

Later in her life she told her grandson Hal Harvey that newspaper reports at the time listed the notable figures who had died, but simply described the rest of those who perished as "steerage".

"She went to her mother and asked what 'steerage' meant and she just replied 'normal people'. That's when her brain exploded," he says. "She suddenly became the liberal of the family at the age of 11."

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum London

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum LondonAfter attending the prestigious Wellesley College in Massachusetts, she studied at the University of Oxford before moving to Vienna in 1926 where she had her daughter Connie who was born following a short-lived marriage.

Her move to Austria was inspired by her hope to be examined by the revered psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud.

The number of patients who were already on his books meant that Gardiner was referred to a colleague, but it did nothing to dampen her interest in psychoanalysis or her love for a city where the Social Democrats were in charge.

"When she arrived there it was 'Red Vienna' and she was very taken by the social reforms that were taking place," Ms Seigel says. "Muriel Gardiner liked living the city; the analysis went well and she decided she wanted to become a psychoanalyst."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe enrolled at the city's university to study medicine but, before long, the socialists were swept aside by a fascist regime that hunted them down.

Rather than abandon the volatile country, Gardiner combined her studies with a new cause - aiding the underground resistance. "She never struggled with making the choice to stay," Mr Harvey explains. "It was just obvious to her to do the right thing."

Known to the resistance movement as Mary, Gardiner owned three residences, including a small cottage in the Vienna woods. Here, she would host meetings and hide resistance members, including the Revolutionary Socialists' leader Joseph Buttinger - a man who by the end of the 1930s had become her husband.

"She was leading this double life, really, of the devoted mother, the active student who was very sociable as well and had lots of friends across Vienna, but at the same time doing this resistance work," Ms Seigel says.

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum London

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum LondonHer work involved smuggling fake passports into Austria so that resistance fighters could flee the country.

She would also use her wealth, influence and contacts to get people out by legal methods, such as by finding jobs for them with families in Britain.

On one occasion, Gardiner travelled by train then climbed a mountain for three hours in the middle of a winter's night to deliver passports to aid the escape of two comrades who were hiding in a remote inn.

"She was genuinely in danger; I mean she was constantly doing things that if she'd been detected, at best she would have just been thrown out of the country, but more likely she would have been thrown into prison herself," says Ms Seigel.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHer Viennese social life brought her into contact with all sorts of people.

In 1934 she began an affair with the English poet Stephen Spender. She got to know future Labour chancellor Hugh Gaitskell who lived in the city for a time. She even met one of Britain's most notorious traitors, as Ms Seigel explains.

"A young man came to see her and she was a bit suspicious about him and what he was asking her to do, and in fact she found he had given her a whole lot of communist literature to distribute, which wasn't what she expected.

"It was only after the war when she saw a picture and read about him that she found out it was Kim Philby, the British double agent."

By 1938, Austria had been annexed by Nazi Germany and Gardiner's daughter and husband Buttinger left the country, although she remained to complete her medical studies and continue her resistance work. Before long though, all three of them departed Europe for the US.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring World War Two, Gardiner and her husband campaigned for visas for Jewish people and helped provide refugees who arrived in the US with jobs and accommodation.

It's impossible to tell how many people's lives she saved. Mr Harvey says he heard it was in the hundreds, "but I don't think she even knew the number".

Several people told a documentary that was released in 1987, two years after her death, that had it not been for Gardiner's efforts they "most likely wouldn't be alive today".

In the decades after the war, she built a busy psychoanalysis practice, taught at universities and published several books, with her resistance endeavours known only to those she had helped or who were close to her.

Mr Harvey remembers her as "a very modest person, genuinely modest". He added: "She would never talk about what happened unless you really prodded her."

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum London

Connie Harvey/Freud Museum LondonBut in 1973, a book called Pentimento was published. The work of US writer Lillian Hellman, it included a chapter about her apparent friendship with a woman called Julia who had lived in pre-Nazi Austria and worked with the resistance.

A film, Julia, starring Vanessa Redgrave and Jane Fonda, came later in the decade, leading to a best supporting actress Oscar for Redgrave.

Ms Seigel explains: "When this [the book] came out... a lot of people started ringing Muriel up and saying: 'Have you read Lillian Hellman's story? Surely you must be Julia? The story she's describing is your story.'

"And Muriel Gardiner, she wasn't somebody who wanted to make a fight out of something, but she did write to Lillian Hellman and said: 'Oh, bit strange, you know, did you get this from me?' and Lillian Hellman didn't actually reply."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA connection was discovered between the pair: they had shared the same lawyer, Wolf Schwabacher. As he had died by the time the book was published, he could not reveal if he had ever told Hellman about Gardiner's story.

However, former members of Austria's socialist resistance insisted there had been only one American woman who worked with them in the 1930s, and that was the person they knew as Mary.

One result of the controversy was that Gardiner finally made her story public by writing her memoir, Code Name Mary, which has long been out of print but is being republished for the Freud Museum's exhibition.

The Hampstead-based institution, Freud's final home after he left Vienna because of the Nazis' persecution of the Jews, was bought for the psychoanalyst's family by Gardiner and later became a museum with the help of her charitable foundation.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor Ms Seigel, this was a key reason for holding the exhibition.

"We feel very strongly about Muriel Gardiner because in a way she and Anna Freud were the founding mothers of the museum and the reason that it's in existence at all.

"Her foundation has been incredibly supportive for a long time so it's partly to say thank you to them as well."

Vanessa Redgrave - whose life again became entwined with Gardiner's when she wrote a play that featured the American psychoanalyst heavily - is also involved. She is hosting an event at the museum about the resistance hero along with refugee campaigner Lord Dubs, who was himself saved from the Nazis by another hero, the Kindertransport mastermind Nicholas Winton.

Gardiner's grandson says it is "gratifying" to hear about the renewed interest in her.

"She contrived to give away 99% of her wealth, and she did it," Mr Harvey says. "She was no Mother Teresa - she liked a good meal, she loved a vodka tonic at the end of the day.

"But combine the money she was lucky to get with her sense of ethics and ability to conquer fear, then you really had a woman that society needed."

Code Name Mary: The extraordinary life of Muriel Gardiner runs at the Freud Museum London from 18 September to 23 January