Retail survivors: The London shops that have been trading for centuries

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe coronavirus pandemic has led to the hardest times for retail in living memory, although there are some businesses in London that have a history that goes back hundreds of years. How have these traditional shops fared in such a challenging environment?

London's streets have pulsed with people and enterprise for many centuries but when the coronavirus pandemic hit, the capital fell eerily quiet. A record number of shops closed on the UK's high streets as footfall dropped alarmingly.

Some of London's retailers have been around long enough to have gone through not just both world wars, but also the abolition of slavery, the establishment of the world's first underground railway and the founding of the Metropolitan Police.

The BBC has spoken to four of the capital's ultimate retail survivors - which together can boast nearly 1,000 years of trading - about the trials of the past 18 months.

'We are the custodians of the business'

The origins of London's oldest surviving food shop, Paxton & Whitfield, can be traced back to a cheese stall in Aldwych market in 1742.

As London became increasingly affluent, the cheesemonger moved closer to its wealthy customer base, near Jermyn Street in the West End, where there is still a shop today.

Lockdown presented many challenges, according to Paxton & Whitfield's retail manager Hero Hirst.

"It was how to adapt fast enough to how people want to adapt their buying habits," she said.

After an initial stage of "panic buying cheddar and parmesan that would last well" customers reverted to making smaller-scale purchases.

"A lot of sales switched to online, and we were able to meet that demand very suddenly."

Paxton and Whitfield

Paxton and WhitfieldPaxton & Whitfield, which has two shops in London and another in Bath, found that its second shop in the capital did very well during lockdown.

"Footfall was very, very low in the centre of town, but our village green-type place in the middle of Chelsea was incredibly busy."

Lockdown led to "some real unexpected benefits", Ms Hirsh said, explaining that this period might have helped shape the 279-year-old business's future.

"Expertise and guidance are really fundamental to how a business like ours works - you can buy cheese from lots of places," Ms Hirsh said.

With in-store cheese sampling no longer an option, they decided to offer an online service with an expert cheesemonger to guide customers through cheeses delivered to their homes.

This proved to be "way more popular" than the in-person approach. "We can now offer those classes all over the country. That's definitely something that's staying."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStaying small and agile has helped the family business survive this long, Ms Hirsh said.

"After World War Two we did become a grocery store because of rationing, until 1954. The fact we're a small business, and we've always been family-owned, means we're able to implement things quickly."

She added: "Because we've been trading so long, everyone here understands they are custodians of the business. Anyone who acts a custodian for Paxton & Whitfield does feel a duty to keep it going.

"There must be a very good reason that we've been trading for over 275 years."

'It's the first time we've shut in 350 years'

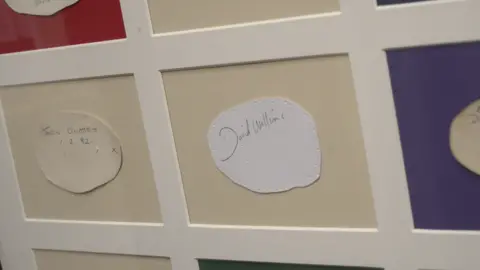

Founded in 1676, Lock & Co has sold handmade hats to, among others, Admiral Lord Nelson, Charlie Chaplin and Jacqueline Kennedy.

Despite its reputation for upholding tradition, nonetheless the hat-maker has long prided itself on "remaining on the cutting edge" - the iconic British bowler hat and the grey top hat are both Lock & Co creations.

Roger Stephenson, the deputy chairman, said: "We've survived depressions, recessions, two world wars and were even here when Wellington was beating Napoleon.

"Lockdown is the first time our business has ever had to close in our whole history."

As the UK's social calendar dried up to help stop the spread of coronavirus, so too did Lock & Co's market.

"We normally supply weddings and garden parties, but no-one had any reason to go out," Mr Stephenson said.

The build-up to Royal Ascot, the yearly horse-racing meeting where fashion is all important, is normally the busiest period for the hat-maker.

The five-day festival, traditionally attended by the Queen, can bring in up to 25% of the shop's yearly income, but last year Royal Ascot was held behind closed doors.

Mr Stephenson, the seventh generation of his family to work at Lock & Co, said: "We were able to look back at what my grandfather and father and those before them had gone through.

"You try and conjure up some of that 'Blitz spirit' I suppose, to keep the show on the road and look at the positives. But this pandemic was so unprecedented.

"It was a scary time for everyone, but I think we grew into it. The website is something we've been growing anyway, and we really concentrated on our digital offering."

Despite the challenges presented by coronavirus, Mr Stephenson says Lock & Co is already "bouncing back".

"Providing good products and good business hasn't changed in 350 years."

'You can't take an appendix out over Zoom'

Henry Poole & Co has been described as the birthplace of modern black-tie dressing.

The family-run business helped to make Savile Row the world's the most famous location for bespoke men's clothing.

Founded in 1806 as a military uniform-maker, its tailors invented the tuxedo for King Edward VII who wanted an alternative to tailcoats for some occasions.

Simon Cundy, managing director at Henry Poole, said the past 18 months had been "the hardest period the tailoring trade has ever been through".

"Suddenly in this pandemic, it's been a complete shutdown of all markets. Even in war times, we had many patrons come over from the Americas who were residing here for the war effort."

Business shrunk to the point the company experienced only about 20% of its usual turnover.

While Henry Poole & Co has been able to make some online sales, the core of its work cannot be done remotely, said Mr Cundy.

"Fitting a suit on Zoom is like a doctor giving a patient a needle and thread and telling them how to take out their own appendix," he said.

"There's a one-to-one aspect in our trade that drives our business; like a doctor or dentist, but with better news."

He added: "I'm sitting on around 200 suits waiting to be fitted. It's a complete backlog. I've got the work, I just can't physically go to people to fit it."

The signs are already pointing towards another "Roaring Twenties" now that lockdown is over, Mr Cundy believes.

"There will always be a need to dress up and throw a party.

"Already, colour-wise, people want a lot more vibrant. There's a flamboyance to our new orders saying 'we're out of this and we're going to celebrate in style'."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlthough the domestic market is reviving, Mr Cundy is still waiting for global travel to open up as Savile Row tailoring is international - the Japanese word for suit is "sebiro", a truncation of "Savile Row".

In normal times Mr Cundy says he would be flying to North America, Asia and the Middle East to fit suits to clients.

"We're still at only half capacity and we will be until we can think of a way to get our travel sorted."

'Flowers make you tough'

Moyses Stevens, which has been selling flowers to Londoners since 1876, is the capital's oldest florist.

Over the decades, it has collected several royal warrants, including one to supply the Duchess of Cambridge with flowers.

In normal times the handiwork of the florist could be seen in hotels across London, but when lockdown hit, 90% of that work dried up, according to operations manager Gemma Kavanagh.

"Revenue through weddings, which are a big part of our business, obviously dropped to nothing too," she said.

Lockdown was "different, not disastrous", though, with people still having occasions to celebrate.

"The first lockdown took place after Mother's Day," Ms Kavanagh explained. "We would normally receive around 100 orders a day, but that got to more than 300 per day."

She added: "Instead of sending flowers for special occasions people began to celebrate more normal occasions. Flowers to celebrate dates people should have been having, 'we're thinking of you' flowers etcetera."

Ms Kavanagh, who has been working in the floristry industry since her first Saturday job at 14, says "being a florist toughens you up".

"People think it's all pretty flowers, but it's hard work - we have to deal with really cold weather, arranging flowers with no heating, work with our hands all day," she said.

"It's something you have to do because you love it, and that breeds a small but strong community."

Moyses Stevens is resilient in part because of its long history, Ms Kavanagh says.

"We're lucky to have such a heritage behind us. I think it makes you fight harder than you thought possible to keep it going, given it's been around for so long."

Not being able to see customers made the florist realise the "importance of community", Ms Kavanagh said.

"Customers were calling the head office every day or messaging over social media checking up on our staff.

"That's why we realised our high streets were so important. All our shops are little hubs for people to come in to see the flowers and always see a friendly face and have a chat.

"This is why we've weathered every storm that's been thrown at us. This is why the industry will survive."

Video journalism by Gem O'Reilly