Riots 10 years on: The five summer nights when London burned

PA Media

PA MediaOn the afternoon of Saturday 6 August 2011, about 300 people walked from London's Broadwater Farm estate to Tottenham police station.

They are seeking "justice" and "answers" over the death of a local man called Mark Duggan, who had been shot dead by police two days earlier.

"We went down to the protest with the family. We went down there to talk to one of the head police officers and they said it would be a few hours.

"Ended up, we were waiting for about five hours. Then one of the head police comes out and says, 'the police can't deal with this right now', and we have to come back another day.

"People started to stand in the middle of the road to stop the traffic to show them we're serious, that we're not going to go away.

"I remember myself personally lying in the middle of the street spread-eagled, so traffic's not passing here.

"I lie down in the road, then others joined me. It got to about maybe 8pm, and I remember the chief of police, whoever it was, he wasn't coming out again.

"And I thought - we go to war."

What followed was the most severe civil unrest the UK had seen for a generation.

For five nights, London was engulfed by fire and violence.

The uprising spread across England, including to the cities of Birmingham, Salford, Manchester, Liverpool and Nottingham.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt the end of the rioting, five people had died, including a 68-year-old man who was attacked while attempting to stamp out a litter-bin fire in Ealing.

Dozens of people were left homeless and more than 200 people were injured, the vast majority of them police officers.

There was no government inquiry into the causes and consequences of the riots.

Conducted by the London School of Economics and the Guardian, the social research project Reading the Riots interviewed 270 people who were involved in the disorder. The interviews were done anonymously to allow those involved to speak more freely.

The police officers' accounts in this story, gathered separately by the BBC, are in bold text; the rioters' words are in italics.

Thursday 4 August

Duggan family

Duggan familyIt's about 18:15 when the minicab in which Mr Duggan is travelling is forced by police to pull over.

He is being monitored by Operation Trident, a unit of the Metropolitan Police focused on gun crime in London's black communities. Undercover officers are following father-of-four Mr Duggan from a meeting with another man, who they suspect was selling him a gun. The aim of their operation was to take the gun off the streets, Mr Duggan's inquest would hear.

As the vehicle comes to a stop, the suspect leaps out. An officer fires twice. The first shot passes through the 29-year-old's arm and lodges in another officer's police radio. The second shot hits Mr Duggan in his chest. It is fatal.

A gun is found about seven metres from where Mr Duggan was shot. It had not been fired.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) later announces it "may have given misleading information to journalists to the effect that shots were exchanged" between Mr Duggan and the police.

Friday 5 August

Members of Mr Duggan's family formally identify his body. The news of his death filters through to those who knew him.

The Metropolitan Police did not adequately inform Mr Duggan's family of his death, nor did it provide appropriate support or keep them up to date with the case, the IPCC went on to find in 2012.

Saturday 6 August

Alan Stanton

Alan StantonThe people who have gathered outside Tottenham police station have been waiting for nearly five hours when they learn that no officers are available to address their concerns.

The nature of the demonstration changes from peaceful to charged. Bottles are thrown at patrol cars. One is set alight; another is pushed into the middle of the road before it too is torched.

Groups of people are arriving in Tottenham from other areas of London. More police are called in.

"There's petrol bombs and bricks being thrown. They had control at that point and a lot of them knew that. As we exited the car park, the van was getting constantly pelted.

"The thing that probably scared me the most was that the side door was about to fly open.

"Some people think that the police are some anonymous robot out there. We're not. Back at home, my wife and my kids were scared."

Getty Images

Getty Images"We jumped in a vehicle, about six geezers, went down there. Straight to the combat zone.

"People just started to come from everywhere. There was a lot of anger and frustration in the air.

"I grew up with Mark, yeah? We're used to being stopped by the police. But it's like they've taken foul play to a whole new level."

Riot police and officers on horseback are sent in to disperse the crowds. They come under attack from people throwing bottles, fireworks and other missiles.

"We're talking bottles from the off-licence down the road being set alight, made into firebombs and thrown at us.

"At that point, it hit everybody in the bus that this is the real thing, and they potentially may die."

A couple of hours later, a double-decker bus is burnt out. Shops are set on fire. Looting begins. Vision Express, Boots, Argos and JD Sports are ransacked.

Without the manpower to make mass arrests, the police priority is to disperse the rioters to let fire engines reach burning buildings.

Word of the violence spreads and attracts more people to the scene, including those who were just curious.

"My 14-year-old brought me her phone with a picture of a burning car and said: 'Mum, that's on Tottenham High Road.'

"I said to my daughter: 'Do you want to go there, and see what's going on?' So we did, on our bikes.

"I went into the corner of a little shop because I didn't want anything to blow up and burn me up. We were like nurses because all the wounded were coming to us. I saw guys with their hands sliced open, skin hanging off.

"I took them ice water, I washed their wounds, and told those that are not that injured, 'go back and fight' because I didn't care.

"I think the policemen deserve a bloody good hiding. They have no right to go and kill no-one."

Sunday 7 August

Getty Images

Getty Images"As we got closer, we could make out the silhouettes of rioters. The noise then started to increase dramatically. Communication became much more challenging purely because of the noise. It was almost impossible to hear the radios.

"It was a possibility that we might get shot at, particularly if we were lured too far forward. And I also saw what appeared to be machetes being dangled down by the side of their legs.

"It could all come to a very grisly end."

Police condemn a wave of "copycat criminal activity" breaking out in London. Fires set across the capital are now largely under control, the London Fire Brigade (LFB) says. That afternoon, police announce there will be an investigation.

As dusk falls, violence bubbles up again. Police are called to Enfield, Brixton and the Oxford Circus area. Riot and mounted officers patrol the streets.

"It was an absolute warzone. I walked up there, saw about five youths, all faces covered up. They set a wheelie bin on fire and threw it into the riot police.

"I saw about 16 men, all in grey tracksuits. They came from other parts and said: 'Today, we are putting down the postcode war. Today we're here to help you.'

"And I call them soldiers. And they stood united together on the frontline, pelting the police. And that was really, really nice."

Looting quickly becomes a driving force behind the unrest.

The first shops targeted are clothes shops and shops with high-value electrical goods.

Getty Images

Getty Images"Everyone was scared to start it off. So, someone dashed a stone at a Maplin's window.

"And then it all kicked off. It was like, 'I'm going to get four TVs - well, I'm going to get five.' It was no drama, no stress, everyone had the power. Everyone had the strength.

"The police weren't in control. We had the power."

"The chief inspector operating on the High Road phoned me up to tell me they're exhausted, they need a break, is there any relief for them?

"And I had to say to him: 'You're not going to get any more resources in the immediate future. You've got what you've got, you're going to have to try to hold the street.'

"And he wasn't sure if I was telling him the truth. In fact, he said to me, 'are you joking?'"

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTottenham Hale retail park is being smashed and sacked. Looters run down the road carrying plasma televisions. Brixton's Effra Road retail park is under a similar onslaught.

"I actually found this iPod and as I picked it up, this girl was looking at me.

"I just gave it to her. I went in one of the shops took a load of cigarettes, and actually gave it away to an old woman.

"Only kept one packet for myself, a pack of 40."

"Supermarket trolleys were being used by the rioters to stock up with bricks from a nearby building site and they're wheeling them around to their own frontline and then using those as immediate replenishment.

"People wanted to hurt us. People wanted to hurt us really, really bad."

Getty Images

Getty Images

Monday 8 August

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe early hours see more shops set alight.

Looting and vandalism spread to Waltham Forest, Islington and Ponders End.

"It felt fine, it just felt natural. Like it was just a normal day. Everyone was doing it and no-one was getting caught.

"I was seeing people 70 years old, walking in JD Sports with those pulling-things they use, like a bag on wheels. They were just filling up and walking out. So I'm thinking, 'these are just old people and they're still robbing'.

"It's just like that rush where you think, 'oh, my God, you can get anything.'"

Firefighters are called to Enfield, Brixton and Walthamstow.

"Everyone just clicked and said, 'yeah, this is our chance'. Do what we have to do. Cause mayhem. It felt like we were on a leash for years and we've come off that leash.

"Every type of person was there. There was some guy, a white guy, in shorts, flip-flops and a straw hat.

"It was really enjoyable, actually. At one stage, it was like a street party. I just went down there as a spectator. I really did.

"Lots of us went along, just to watch, but found ourselves caught up in it."

Getty Images

Getty Images"One male that I arrested from Effra Road - when we were sat in the custody suite, I asked him, 'what were you doing there, what were you doing?' And he had quite clearly come out from Currys and yet he still said, 'you shouldn't have killed Duggan'.

"And I kind of turned to him and said, 'but you were burgling a shop'. And it just seemed to me that they were fixated on this Duggan being the reason.

"But why would you burgle an electrical store because police officers have shot a man?"

"I went to see how they were getting things, and they were sliding underneath the shutters and that.

"So I think to myself, 'I'm not getting on my hands and knees to get no goods'.

"So I came up with a cunning plan, and I stayed outside. Waited for someone to come out with something that I wanted - and I just took it from them. The car was round the corner and I just put it in the car, come back and do the same thing."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter a lull during daylight hours, skirmishes break out again as evening approaches.

Hackney and Peckham see rioting and fire-starting. By the time darkness has fallen, fires are burning in Croydon and Ealing.

Police are overstretched and cannot put on an imposing display, nor make mass arrests.

"It felt like a battle as there was police against us, and for the first time, we felt like we could actually take them on.

"Every rock we could get hold of, we were throwing at them. Stones, chairs, coins, shoes... anything goes."

"A bottle bank had been upturned and a hell of a lot of those bottles were thrown at us. There was a lot of chat on social media about people looking to kill a police officer.

"I was on duty the night that Keith Blakelock was murdered in Tottenham and I heard his serial screaming for help on the radio; one of the most haunting things I've ever heard.

"It could have happened to us that night."

Police officers from the Essex and Suffolk forces are sent to help the Met.

Prime Minister David Cameron, London mayor Boris Johnson, Deputy Prime Minister Nick Clegg and Leader of the Opposition Ed Miliband return to London from their various summer holidays.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Tuesday 9 August

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs the clock ticks into a fourth day of unrest, disorder spreads beyond London. A police station in Handsworth, Birmingham, is set on fire. One in Nottingham is firebombed. Cars burn in south Liverpool. There's rioting in the centre of Manchester, in Salford and West Bromwich. In the Bootle area of Merseyside a dumper truck is used to break into a post office.

Disorder is now breaking out in 22 London boroughs.

"We didn't have any clue that Croydon was going to feature in the way that it did, but then the scale jumped and quite quickly turned on a sixpence.

"People in the roadway started to put on balaclavas and face coverings. A couple of lads on a moped came right up to the line - they were counting us and then they went back. Then the whole crowd started marching up the road, with a four-door saloon car as a figurehead.

"It came at us full speed, there was no intention to scare us - they were trying to run us over. It was absolutely, without a shadow of a doubt, attempted murder."

Rioters are not just attacking the police and looting - they start to set fire to their own neighbourhoods, including shops with residential flats above. Among the targets is a local landmark, the 140-year-old Reeves furniture store.

Lewisham has roaming groups of people stirring up trouble. At least 100 people loot a Tesco in Bethnal Green. Fires are started in Lambeth, petrol bombs thrown in Hackney.

"Everybody had matches, fuel, petrol bombs. Because we wanted to see everything on fire. To show them, 'what can you do now? There's nothing you can do'".

"I saw McDonald's get set on fire, and then it was completely set alight, and I've petrol-bombed it, even though it was set alight. And I felt good."

Croydon continues to burn.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Wednesday 10 August

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr Cameron says there are contingency plans for water cannon to be used at 24 hours' notice. The Ministry of Justice says there are enough prison places for all.

Eventually, the rioting comes to an end.

"What made everything stop? Easy. The shops ran out of stuff.

"Currys went instantly. All the phone shops went instantly."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMagistrates' courts in London, Solihull and Manchester among others stay open through the night to fast-track those already in custody for disorder-related offences.

"What I'm really upset about is that they didn't do it right and there's greedy kids out there who were doing it for pleasure, and they should have left the shops and concentrated on fighting the police.

"They were fighting the police for a rightful cause. The shops did not trouble them. That's the shops their mums and their gran have to go to. The post office - they've got grandparents - there's no post office for the elderly.

"Should have got it right, man."

Friday 9 September

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr Duggan's funeral is held at the New Testament Church of God in Wood Green.

Police maintain a low-key presence.

The day passes peacefully.

The aftermath

Getty Images

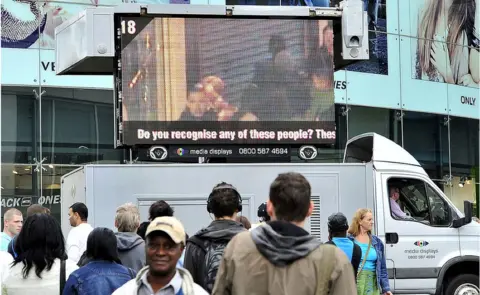

Getty ImagesPolice combed CCTV footage to identify culprits. Over the following months, more than 2,000 people were traced, charged and convicted.

"A friend had come to my house and told me to check out this website showing CCTV pictures and I was like, 'oh, my God, I'm on it. Like, I'm on it.

"I had, like, five, six pairs of shoes in my hand. And it was blatantly obvious they were stolen. And then someone asked me for a pair and I gave them a pair, and the street cameras caught my face.

"And that's how I got caught."

Richard Gough

Richard GoughThere was no official government inquiry after the riots, but there were reports by other bodies.

Opportunism, social deprivation, discontent with the police and unemployment were all mentioned, but a single overwhelming cause for what happened over those five days in August was not pinpointed.

Over the days that followed, the police were roundly criticised. The Met later acknowledged that its inability to monitor social media meant it could not get ahead of events.

Analyses following the riots found that police tactics were hampered by inadequate numbers, that they should sometimes have intervened more promptly and assertively, and that intelligence was flawed.

They all praised the bravery of the officers on the frontline.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMinistry of Justice figures show a total of 1,292 offenders were jailed for their part in the trouble.

Rioting was seen as an aggravating factor. Sentences were longer and more people were sent to prison than would normally be expected for the same charges under different circumstances.

"At least I can tell my kids when I'm older, and my grandkids, 'I've been involved in a riot'. Nice little story for them, isn't it? You know, like World War Two and that with my great-grandads.

"I do not regret it. If it was to happen again, I would happily join in. Anything against the police, I would happily join in.

"Everybody feels happy that it happened. Everybody."

Getty Images

Getty Images"I wasn't there for the robbing. I was there for revenge.

"I'll always remember the day that we had the police and the government scared. For once they were living on the edge, they felt how we felt. They felt threatened by us.

"That was the best three days of my life."

"When I got up on Tuesday afternoon and rang the office I was told I didn't need to be in till 18:00. I had the opportunity to take my dog out for a walk in the park.

"It was almost bizarre in that this was the first quiet time that I'd had, when no-one was trying to kill me.

"It was nice."

Getty Images

Getty Images