Covid-19: The NHS trust the Army is helping through the second wave

BBC

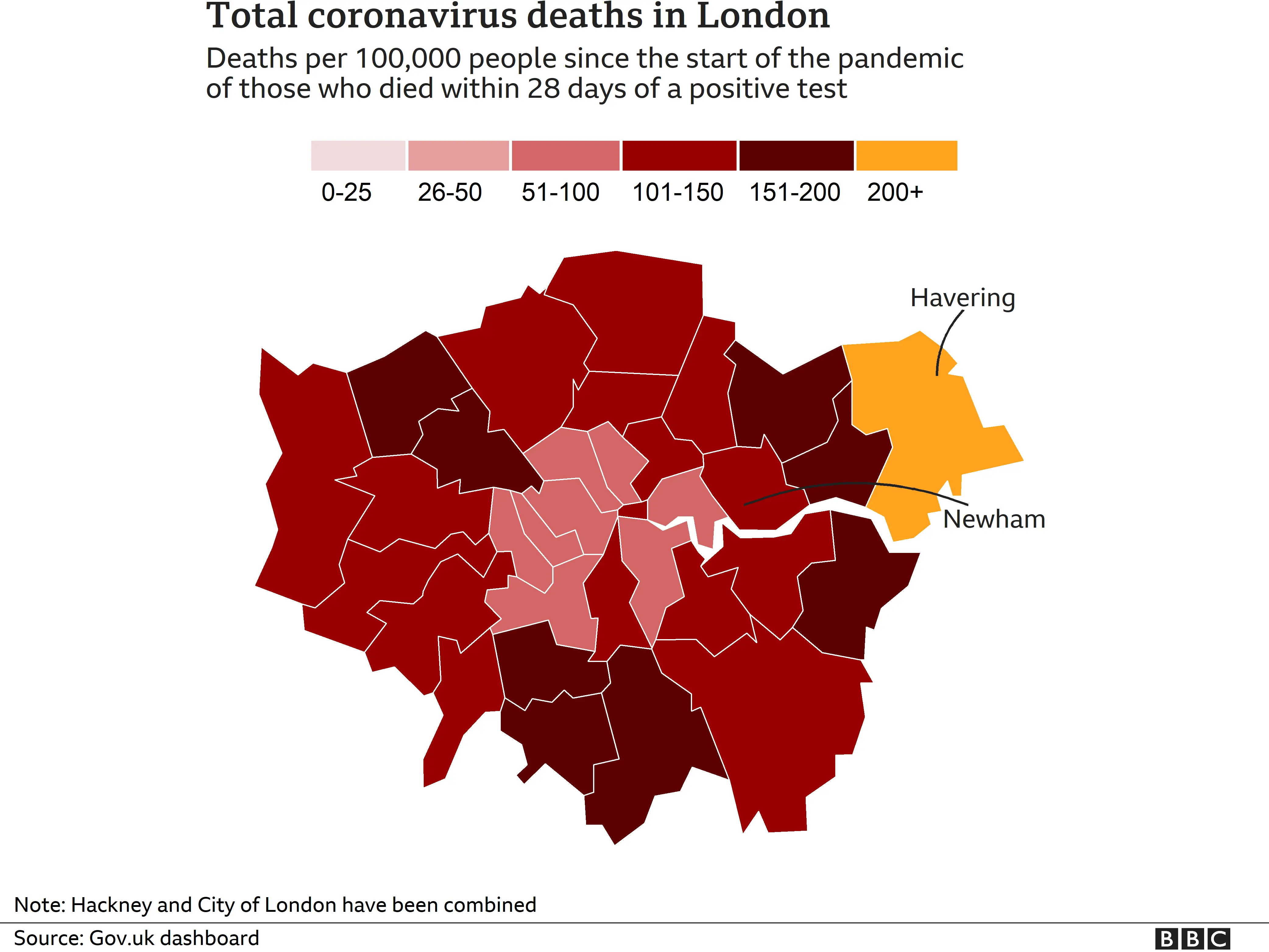

BBCBarts Health NHS Trust runs five hospitals in London. It has the highest coronavirus death rate in the capital.

A key difference between the first and second wave is the mortality rate. Much has been learned about the virus, and patients who might have died in the first wave are being kept alive.

This means Barts is even more overstretched than it was in the spring.

"Nurses are physically and mentally exhausted," says Nicola Rudkin, a senior nurse at the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. "They've not had a break or been able to travel back home to their countries.

"They didn't get a break for Christmas."

Medics have been working shifts at hospitals across the trust, as it makes more sense to move staff than critically ill patients.

"We always feared there would be a second peak and, sadly, it has happened," Nicola says. "It has been far worse than we imagined. The numbers have been way in excess of what we hit last time. In April, at the peak, our patient numbers were 86. We have had 151 as a peak in the second wave."

"We can build the wards, fit them with equipment," Nicola adds. "But what we can't do is get critical care nurses from nowhere.

"To help, we now have 40 medical combat technicians and 10 soldiers who have just come back from deployment in Oman."

Reuters

ReutersThere is plenty for the new recruits to do.

The 40 medics will work as healthcare assistants, to help reduce the workloads of doctors, while the other soldiers will carry out non-clinical tasks such as stacking medicine trolleys, cleaning and doing laundry.

About 210 Covid patients are in intensive care at the five hospitals run by Barts - the Royal London, Newham, Whipps Cross, Mile End and St Bartholomew's. Apart from St Bartholomew's, the NHS trust's hospitals are in parts of east London where the second wave of the pandemic has hit hard.

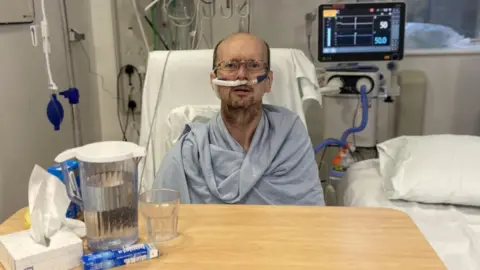

Douglas Johnson, who is being treated at Newham Hospital in Plaistow, is one of those patients. The 55-year-old drove the 145 bus route around Dagenham and Ilford until he fell ill at the start of the month.

"I have been in here three weeks now and I get very anxious," he says. "Every day is a completely new day I don't know where I am. It is worse on my mind than it is my body.

"When I first got it I did not know what to think. I couldn't breathe. I am better now after three weeks.

"I worked the whole of last year, no furlough, and I'm just unfortunate I got it now. I haven't seen my wife. It's not nice and quite upsetting. Sometimes I get emotional."

Barts' main hospital is the Royal London, where 12 of its 15 floors have wards with coronavirus patients.

The hospital has space for 155 such patients, and currently has fully equipped empty wards in case Covid cases continue to climb. The overriding hope of doctors and nurses here is that these wards won't be needed.

Ten months of Covid have taken their toll. Many staff are physically and mentally exhausted.

Robert Christie, who has worked as a nurse in intensive care for 16 years, says he goes through each shift with a range of emotions.

There is anger, and apprehension too, about the dangers of the tasks in hand. He also worries that patients aren't getting the one-to-one care they deserve, but says there can also be euphoria when colleagues pull together to save lives.

"It's been crazy, really," the 42-year-old says. "It has felt very different to the first wave.

"The second wave started differently - much slower and more gradual - but then things seemed to change and you felt a change on the ward the week before Christmas. That's when the admissions really started to pick up pace and they first started talking about the new coronavirus variant."

Reuters

ReutersRobert has worked through terror attacks, which are hugely demanding over an intense but short period of time. Covid is different.

The first wave of the virus tailed off relatively quickly, Robert says, although he fears the second wave is going to be much more prolonged.

He says that from the week before Christmas, each time he started a new shift, things had changed.

"The pace was picking up and we still are in the thick of it, really. People are getting emotional, cracks are beginning to appear, as they realise that this potentially could go on for months.

"The patients that do get better from Covid don't get better quickly. With Covid it takes a long, long time to recover. A normal ICU (intensive care unit) stay is seven to 14 days, but for Covid you are looking at two, three or four weeks. Some patients have been here for upwards of 30 days.

"Those that are going to get better are going to do so slowly, and those that aren't going to get better are going to die. And there are a lot of deaths."

Oliver Legaspi, who works as a dialysis nurse at the Royal Free Hospital, is currently a patient at the Royal London. He has spent more than three weeks in intensive care.

"I have been here since 29 December," he says. "It is a worrying time. I thought I was not going to make it. I am much better than I was. They have just started to wean me off [ventilation].

"Of course I was worried for my family but they keep me fighting."

Oliver is one of the lucky ones.

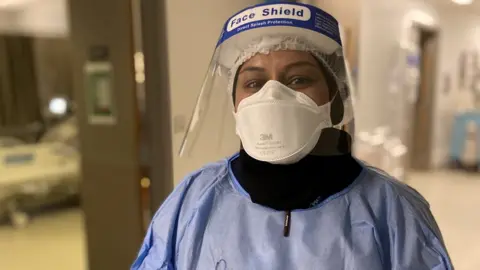

In a corridor on the 13th floor of the Royal London, 39-year-old nurse Boshura Khatun is coming to terms with another upsetting case.

"We have a patient who came in with Covid and he has deteriorated overnight and it looks like he is reaching the end of his life so we have called the imam to say a prayer, as religion is such an important aspect for many.

"I have seen a lot of death on this ward. In the last week I came in for three night shifts and had two people die each time. Six in total, and it is traumatising without their families being here to hold their hands so sometimes we do it.

"Then when I go home I have to be a mum to my boys and I don't want them to see me upset, so it is tough. There are nights where I don't sleep."

Elizabeth Abraham, from Dagenham, is a matron at Newham Hospital. She has just marked 15 years' service with the NHS, having moved from India to the UK.

She has treated patients with HIV, anthrax and rabies, but says the Covid-19 pandemic has been her biggest challenge.

"There are people in their 20s, 30s and 40s this time," Elizabeth says. "We have two teachers, two ambulance drivers, pregnant women and a supermarket worker.

"Sometimes we have been treating our own staff and families, which has been a very close-to-home situation, and that is a big challenge because in the midst of this we make sure our patients are safe.

"I came to this country to do a job and that is my main thing. It is a marathon, 10 months so far, and we'll be here until the end."

It's a sentiment that is echoed by her colleague Kathryn Cannon.

The 32-year-old nurse says the second wave is the hardest time in her career.

"I am glad I am part of it," Kathryn says. "Every day I come in I feel I am doing my bit... it doesn't feel like I am getting there at the moment but that's how I try to face each shift. We'll keep going.

"I think lockdown is hard for everyone. We are in lockdown too, we haven't seen our families for months. My family is worried about me. I'm a grown adult but I am still their daughter and they do check on me all the time, and do wish that I was not here."