Oyster card: The growing fortune that remains unclaimed

Alamy

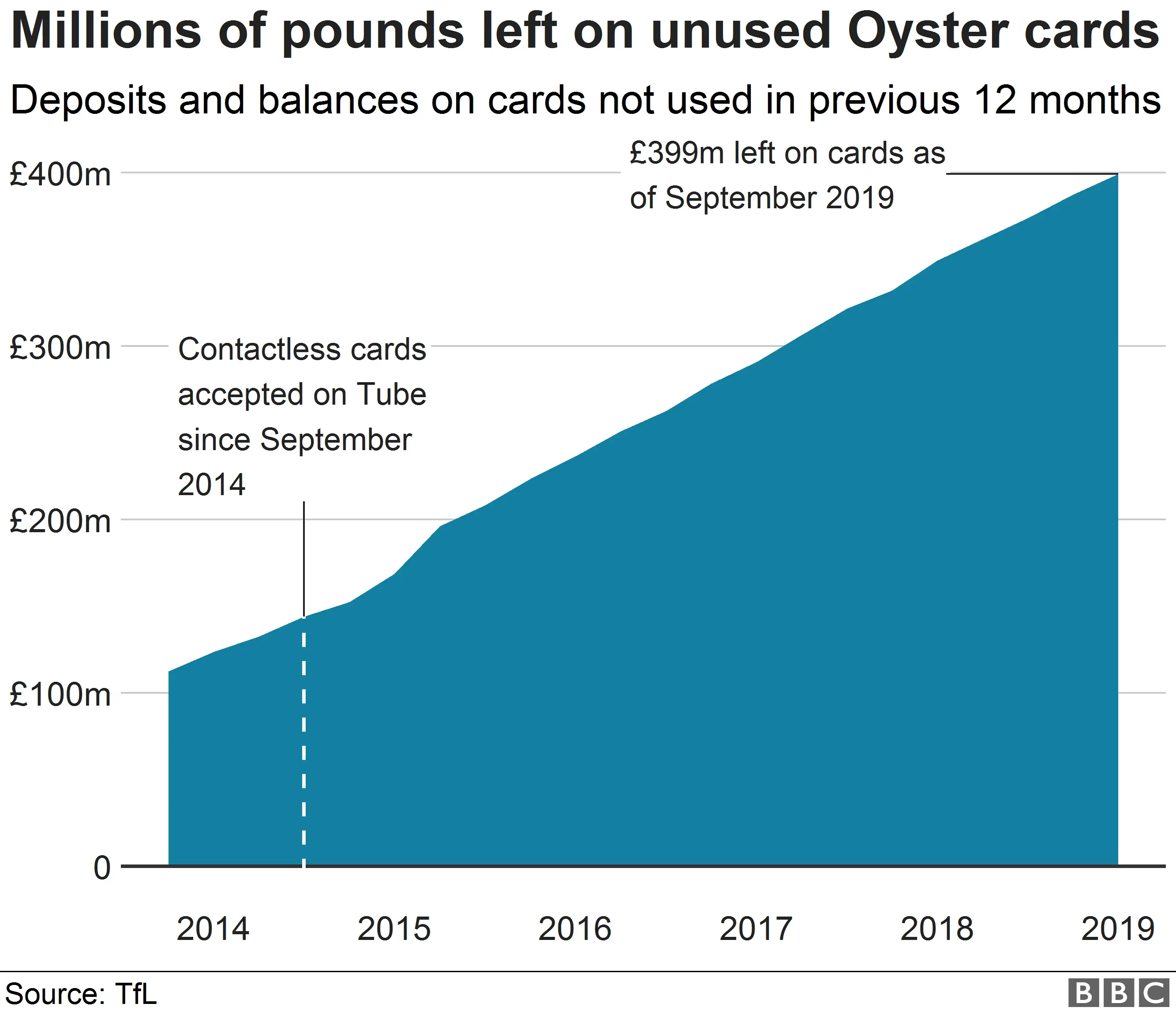

AlamyOyster used to be the go-to way of paying for travel around London, but 66 million of the blue plastic cards haven't been used in at least a year. And while they languish forgotten in drawers, bags and wallets, Transport for London (TfL) has amassed a fortune in unclaimed balances and deposits - now worth almost £400m.

It's really that much?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYes, more than £399m of customers' cash is sitting in accounts managed by the group treasury for TfL, and is being used to "improve the transport network".

More than half - £202.8m - is made up of the £5 Oyster card deposit; the rest constitutes unused pay-as-you-go balances.

The government body is earning interest on that money but said interest rates are low and it would be "complex" to calculate a figure for the past 12 months.

Any interest earned is also spent on improvements but the money will "remain available" should customers want to use their Oyster card again or request a refund, it added.

Why has it built up?

Getty Images

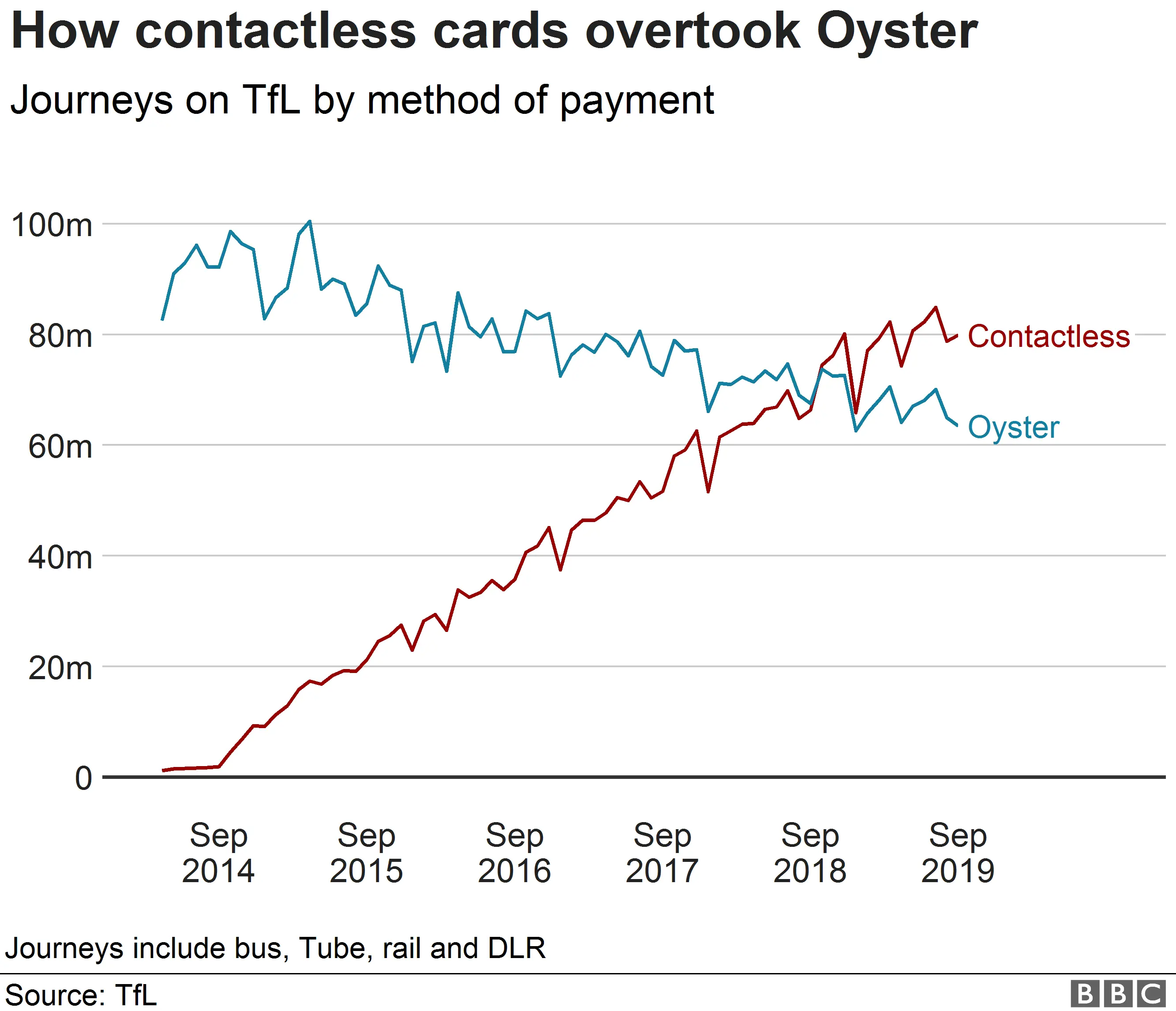

Getty ImagesThere are a few reasons. When the Oyster system was introduced in 2003, it revolutionised travel across London. But journeys made in this way have steadily declined since TfL started accepting contactless in 2014.

About 25 million journeys a month were made on bank cards in 2015-16, the first full year it was in use across buses, the Underground and DLR, compared to more than 99 million a month made using Oyster.

But in 2018-19, contactless and mobile payment has taken the lead with 78 million journeys a month, while Oyster has dipped to about 76 million a month.

So is the Oyster card dying?

In short, no. TfL has issued nearly nine million cards in the past 12 months and almost one billion journeys on the TfL network were made using Oyster in 2018-19.

But the rise of contactless only accounts for some of the 61 million Oyster cards and five million visitor cards that have not been tapped in or out for at least 12 months.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMany are spread all over the world, kept by those who have left London or tourists who visit sporadically and have hung on to it - and consequently the remaining balance - as a memento.

TfL said Londoners also often keep a spare Oyster for friends and family visiting the capital - so naturally, these are used less frequently and may lie dormant for months, or years, at a time.

Why aren't people claiming?

One potential reason is the average balance left on an unused Oyster is £3.46.

Simply put, it might not seem worth the effort. But add the deposit on top and that £8.46 refund might just about pay for a pint in central London.

There are currently 784 cards in circulation that have not been used in a year with a balance of £90 - the maximum credit that can be held on an Oyster.

Surely that's worth digging around in the kitchen junk drawer to see if your card is languishing under a pile of takeaway menus.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSteve Nowottny, from Money Saving Expert, did just that and reclaimed £67.85.

"There's an element of inertia - people see it as a hassle, or they forget about their Oyster card and put it in a drawer, or move away from London.

"Some people assume because it's not registered they can't get a refund or it's a bureaucratic process, but it's relatively straightforward and it's quite satisfying to do.

"People should do it, it all adds up."

OK, I'm convinced. How do I get a refund?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesOyster card credit does not expire and people can apply for a refund whether the card is registered or not.

TfL said it regularly publicises information about how to do so via posters, the Metro newspaper's travel page, the TfL website and via social media.

Those who want a refund can do so at selected Tube station ticket machines, visitor information centres, or by calling TfL's customer service team. Up to £10 of pay-as-you-go credit, plus the deposit, can be refunded in this way. Anyone with larger balances needs to speak to customer services and post their Oyster to TfL.

For those with a philanthropic streak, Oyster cards can be donated at charity boxes at Heathrow Airport, Kings Cross and Liverpool St, which since 2009 have raised £218,000 for the Railway Children.

TfL's chief technology officer Shashi Verma said: "We're committed to ensuring that our customers can get back the credit on their Oyster cards if that is what they want. This is why we regularly publish the amount of credit on cards and how people can obtain a refund if they wish."

What if no-one claims?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt almost £400m, TfL's current "cash mountain" is more than it cost to convert the Olympic Stadium into the London Stadium for West Ham FC (£323m), more than twice as much as London's reportedly most expensive home (£160m) or the annual basic salary of at least 3,700 hospital consultants.

The reality is that year on year, the unclaimed balance grows - 10 years ago, it was £30m. So if no-one bothers to get a refund, the money will continue to sit in TfL's accounts, earning interest.

"It matters because this is money that people aren't using," said Mr Nowottny. "It's wasted from a consumer point of view. TfL makes it clear there's a straightforward way to get the money back, but for an awful lot of customers out there, it's wasted cash and no-one likes wasted cash."

London Assembly member Caroline Pidgeon said TfL should do more to make claiming refunds easier.

"TfL never stops bombarding us with advertisements and information campaigns, but highlighting this cash mountain is one issue that they remain very quiet about.

"I accept that some people living in London might want to keep hold of unused Oyster cards for long periods of time in case they have friends or family staying with them, but this does not fully explain why [the total] keeps on growing."