London violence: How a bloody night became a deadly year

FootballSculoa/Met Police

FootballSculoa/Met PoliceIn the hours either side of midnight on New Year's Eve 2017, four people were stabbed to death across London. The year that followed would become the city's deadliest in a decade.

Long before fireworks illuminated London's skyline, 18-year-old Meschak dos Santos Cornelio answered the buzzer to his Enfield flat on New Year's Eve morning.

He knew who it was - Gaille Bola, a man viewed by the Metropolitan Police as one of the most dangerous and active gang members in the capital.

Met Police

Met PoliceGoing by the street name "G", Bola had been running four county lines drug operations across Hertfordshire. He had groomed Meschak into the notorious Get Money Gang (GMG).

Meschak took charge of one of the phones the gang used while Bola was in prison for a knife offence.

But, after his release, Bola wanted the "drugs line" back.

When Meschak refused, Bola - with two cronies - went to the teenager's flat demanding he return the Nokia phone.

An attack ensued, ending with Bola plunging a knife into Meschak's heart.

After ambushing Meschak, the trio left him for dead and the teenager was airlifted to the Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel, where he would spend the final hours of 2017 fighting for his life.

Doctors turned off Meschak's life support system and he died at 20:28 GMT. Bola was found guilty in November of manslaughter.

Met Police

Met PoliceFollowing the conviction, Det Sgt Brett Hagen said Bola had been known to police for many years.

"Bola is high up on the gangs matrix, of the 3,500 people on it he's in the top 10," he said. "He openly bragged in court about making £1,000 a day from his county lines.

"He went to the property that morning intending to steal a drugs line phone from Meschak and knowing he would use violence in order to steal it. As a result of his actions another young man is dead."

About an hour before Meschak died, another young man named Taofeek Lamidi was found stabbed near a park close to West Ham Tube station in east London. He was pronounced dead at the scene at 20:22.

PA

PADescribed by many as a talented footballer, Mr Lamidi had trials with Chelsea and Colchester United.

The 20-year-old had fallen on hard times following the death of both his parents and his brother being deported back to Nigeria.

"Taofeek was a good kid," said his former coach Patrick Ganlath. "He wasn't bad. What he was, was poor."

On the day Mr Lamidi would have celebrated his 21st birthday the prime suspect in the murder case, Ahmed Mohamed, boarded a flight at Heathrow and went on the run.

Met Police

Met Police"By the time we had taken the case on, Ahmed Mohamed had fled the country," said Det Ch Insp Mark Cranwell.

"We strongly believe he is now in Somalia. This wasn't a gang motivated murder at all, but the two knew each other and there was some beef around snitching."

Hours after Mr Lamidi's murder, a third person was fatally stabbed - this time in south London.

Joseph Payne

Joseph PayneSitting on the top deck of a Route 68 bus in Tulse Hill, Kyall Parnell, 17, and his friends were confronted by another group of youths who got on the bus at about 22:40.

With his hand placed towards his left hip area, Kyall is said to have been "acting aggressively" towards one teenager, according to Det Insp Ian Titterrell.

"There was a suggestion of something glinting," he said. "The three males who had just got on the bus, got off it. They were pursued by Kyall and his friends. Witnesses had seen the chasing group in possession of knives."

Two of the fleeing boys hid in a nearby shop. The other was cornered by Kyall's friends who urged the teenager to "stab him" and to "finish him off".

Fearing for his life, the boy, who was later arrested on suspicion of murder, took a knife from his bag and stabbed Kyall in the chest.

The 16-year-old suspect was however not charged with a homicide offence after the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and Met Police agreed there was a "real issue" of self-defence.

But, the night of heightened violence was not over. Fresh into New Year's Day, London recorded its first official murder victim of 2018.

Steve Narvaez Jara had been at a flat party in Islington when he was stabbed.

The 20-year-old, who studied physics and aerospace at the University of Hertfordshire, died at 03:26.

PA

PAFour men were arrested as part of the murder investigation. But beyond that, details of Mr Narvaez's life and death are sketchy.

There are yet to be any charges. However one of the suspects, Israel Ogunsola, was later murdered on 4 April in east London.

Targeted by teenager Jonathan Abora, 18-year-old Ogunsola was "hunted" and stabbed six times during a sustained attack in Hackney.

PA

PAIn the days and months between the murders of Mr Narvaez and Mr Ogunsola, more isolated spates of shootings, stabbings and assaults saw a further 50 people killed in London.

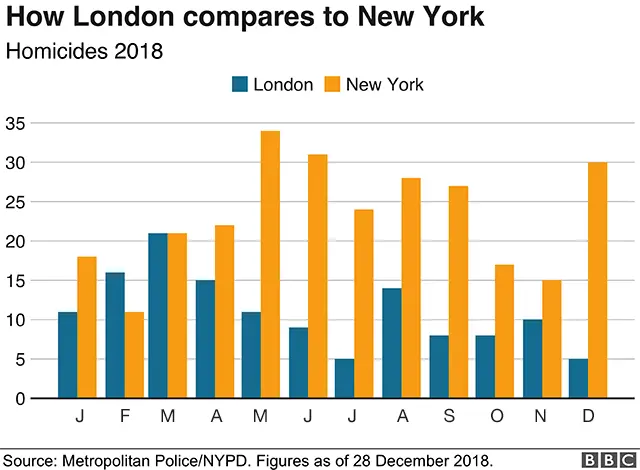

The short space of time between the killings led to London gaining ominous comparisons to New York's murder rate.

As 2018 wore on, however, this proved to be a blip.

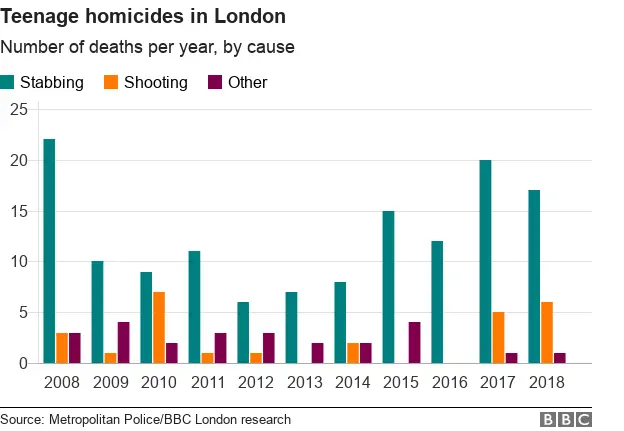

Nevertheless, for the second consecutive year, London's homicide rate climbed to a level which rattled communities and saw headlines of murders become numbingly routine.

Debate among politicians and senior police officers about how to prevent violence was reignited; while a spotlight was shone on the influence of social media and drill music videos throughout much of 2018.

Arguments over the effectiveness of stop-and-search resurfaced, tougher sentencing laws were proposed and Met Police Commissioner Cressida Dick repeatedly expressed how stretched her officers were.

However, detecting any trends or patterns behind the 2018 homicides is as arduous as it is to solve.

The killings were not clustered in certain areas - instead they were spread across London.

The average age of a homicide victim in 2018 was 35. Teenagers made up 17% and a quarter of killings this year are thought to have been related to domestic violence.

Although the issue of knife crime took centre stage this year, only 59% of 132 homicides stemmed from fatal stabbings.

London's victims

Motives and circumstances behind killings varied - as did the age and gender of the victims.

Youth violence is an undeniable issue in the capital. However, criminologist Simon Harding explained the true reasons behind each death were not always plain to see.

"It is much more layered than the screaming headlines lead you to believe," he said.

"What we are seeing with gang killings is more of a stab-on-sight mentality which has seemingly unnerved members of the public.

"There is also a doughnut effect - a ring around inner London boroughs where poverty and inequality is more prominent.

"Every year you are sadly going to have a certain percentage of domestic violence murders. There are also always spontaneous flashes of violence which can happen on a night out and often fuelled by alcohol."

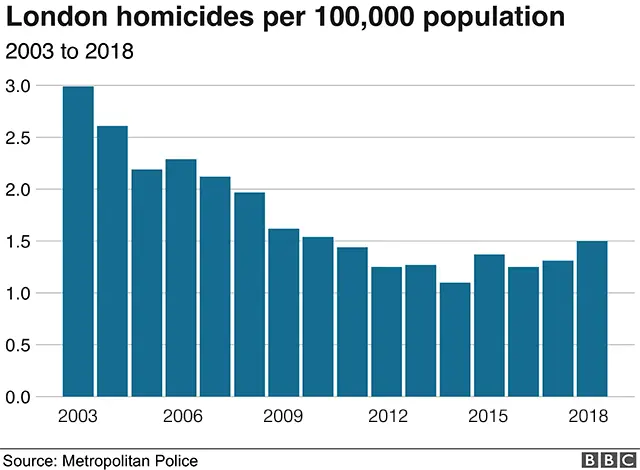

The surge in killings over the last 12 months has arguably plagued London's reputation and infected it with a notoriety of being a violent city.

But, data shows the 2018 homicide rate was significantly lower than it was at the start of the 21st Century - and London's population has risen since then.

Measures have still been taken during 2018 in attempts to halt hikes in homicides - usually in reaction to a batch of violent deaths over a couple of days.

After London endured a spree of killings in April, the Home Office published a new Serious Violence Strategy and ploughed £40m into it.

Prevention and early intervention were said to be "at the heart" of the government's action plan.

Additionally, as the capital's homicide rate reached 100 in September, London Mayor Sadiq Khan described the issue as "a disease infecting communities".

Known as the "public health approach" it sees police officers working with teachers, councils and NHS staff to bring together knowledge of people involved in a criminal cycle.

The mayor set about mirroring methods used to cut Glasgow's homicide rate by creating a Violence Reduction Unit (VRU).

Despite being unveiled months ago, a director to lead London's VRU is yet to be appointed and details of the idea remain vague.

The true influence of these political approaches will have to wait until well into 2019 - perhaps even later.

But, as friends and families of the 132 homicide victims come to terms with new abiding traumas, 2018 is already a year too late.