The man who owns 1,000 meteorites

Graham Ensor

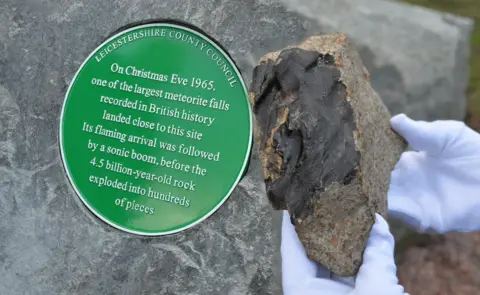

Graham EnsorOn Christmas Eve 1965 a 4.5 billion-year-old meteorite exploded over the Leicestershire village of Barwell.

It was one of the largest and best recorded meteorite falls in British history: witnesses reported a flash in the sky accompanied by a loud bang, followed by a thud as one of the first pieces of space rock landed on the ground. As news of what happened emerged, the media descended on the village and a frantic search for the hundreds of scattered fragments began.

For nine-year-old Graham Ensor, who lived nearby, it was an event that would change his life, sparking an enduring passion for space rocks. The former lecturer now owns about 1,000 specimens, which experts believe could be the largest private collection in the UK.

Leicestershire County Council

Leicestershire County CouncilMr Ensor's meteorite mission has taken him to some of the driest and remotest places on Earth, including in the US, Australia and the Middle East.

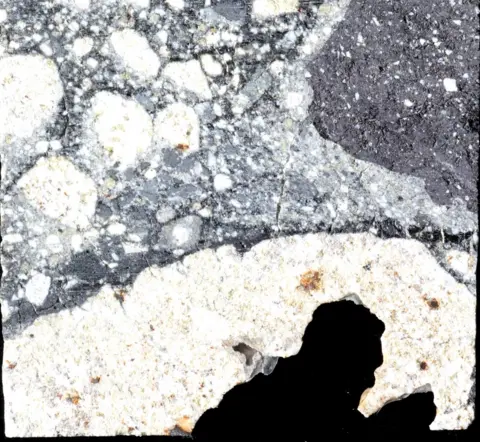

One of his most exciting finds was in the Dhofar region of Oman in 2010. "I had been driving for many miles without a find [but then] I skidded to a halt next to a black rock," says Mr Ensor, who lives with his wife Manda in Leicestershire. "It became obvious it was a very special meteorite."

Weathering revealed tiny white minerals that were formed early in the Solar System. "I picked this meteorite up from the desert where it had been lying for thousands of years [and] formed before any of the planets," he says. "It was such a thrilling and awesome moment.

"There's something wonderful and beautiful about deserts; they gave you a feeling of ancient times and make you more aware of how small you are. Finding rocks that have travelled billions of miles, for aeons, on the desert floor is an incredible feeling."

Graham Ensor

Graham EnsorSadly, many of the best locations for finding meteorites are now "out of bounds", Mr Ensor says, due to political unrest and conflict, although he says there are still a few "Indiana Jones types" who will "jump on a plane hearing of a new fall".

Laws have been introduced as part of a crackdown on meteorites being smuggled out of Oman and meteorite-hunters have even been jailed there. Mr Ensor says the situation is particularly dangerous near the Yemeni border, where people have been kidnapped and held for ransom.

Graham Epson

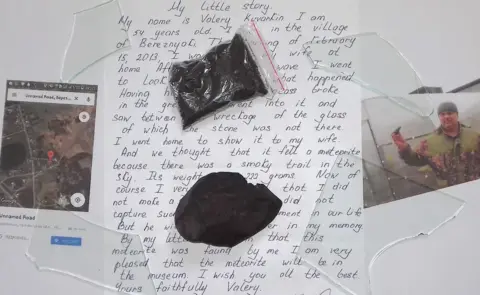

Graham EpsonMr Ensor, now 62, loves the stories behind a meteorite fall and says these days the internet is the safest way to hunt down specimens, with social media being valuable for research and collaboration.

This proved to be the case after a 19m-wide fireball flew across the sky in Russia, before it exploded, injuring about 1,000 people, in February 2013.

Thousands of meteorites, many of them the size of "peas and rice", fell in the Chelyabinsk region and, as happened in Barwell decades before, the event sparked a hunt for so-called "hammers" - meteorites that strike houses or other buildings.

Graham Ensor

Graham EnsorMr Ensor says Chelyabinsk meteorites are now easily acquired but at the time it required a bit of detective work to hunt down a decent-sized specimen. He negotiated with two families to buy one that had hit a greenhouse and another that went through an attic roof.

"[One meteorite] arrived with part of the greenhouse and glass from the impact," he says. "Another one was found in an attic after a damp patch appeared on a ceiling in the spring thaw. When [the owner] investigated he found a hole in his roof and the culprit below it. [I received the] actual panel with the hole in it!

"I am still trying to work out how to make up a display for these."

A 900g chunk of Barwell meteorite made £8,000 at auction in 2009 - some meteorites can fetch hundreds of thousands of pounds - but the former lecturer is more interested in what the objects tell us about the universe than he is in making money.

This has made him friends at the Open University who gratefully borrow and analyse his rocks. One of them, Dr Richard Greenwood, is an expert in planetary and space sciences.

"Graham's collection is large for an individual collector [and] may be the largest in private hands in the UK," he says. "He gets hold of material that is of great scientific value very quickly and brings it to the attention of scientists.

"Everyone at the Open University values the important contribution he makes."

Graham Ensor

Graham EnsorOne of Mr Ensor's most recent acquisitions is arguably one of the most special, coming, as it did, in the year that also marked the 50th anniversary of the Moon landing.

Earlier this year, he was shown an apparently unremarkable orangey-red rock, weighing about 1.3kg, which was thought to have been found in the western Sahara desert - although locations are largely kept secret by nomadic dealers. He believed it was lunar because it shared features with samples brought back by Apollo 11.

"As the soil was carefully cleaned away, it revealed a beautiful and typical lunar-looking stone," Mr Ensor says. In June, the object, which is currently on display at the National Space Centre in Leicester, was confirmed as Moon rock, generating much interest among scientists at the Royal Society.

Graham Ensor

Graham EnsorEven though it was the Barwell meteorite that first got him interested in space rocks, it wasn't actually until fairly recently that Mr Ensor was able to add a piece of the "Christmas meteorite" to his collection.

Nearly 50 years after the event, a 136g fragment that had been left in a box in a family's garage was rediscovered. The rock had smashed through the roof of a hosiery factory that night in 1965, and was found by technician Ernie Wright.

Graham Ensor

Graham EnsorHe took his find home, only for it to be banished to the garage by his wife who feared it could be "radioactive". And there it remained, forgotten for years, until Ernie's son Philip Wright showed it to Mr Ensor in 2013.

The collector, who bought the space rock from Mr Wright, visited the former hosiery factory, which is now a kitchen warehouse, and amazingly found debris from the impact all those years ago - but, sadly, no other meteorite fragments.

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].