Fosse Way: Stories from the road at the edge of the world

Alamy

AlamyThe A46, a roaring dual carriageway used by thousands of drivers every day in the East Midlands, was once the edge of the Roman world, separating civilisation from barbarian. Glimpses of this lost world have been uncovered along its length.

The Romans had invaded Britain in 43 AD with some 40,000 troops and 900 ships, overrunning south-east Britain.

But soon after - the timing and reasons are unclear - the legions paused, creating an ad-hoc frontier along a road running between the major army bases at Lincoln and Exeter.

That road survives to this day as Fosse Way and much of it is still used, as both trunk road and farm track.

Ermine Street Guard

Ermine Street GuardInitially a military route dotted with forts, once the troops moved on, the Fosse Way became a vital artery of the province of Britannia and, at 220 miles (354 km) its longest road.

One of the forts grew into a town, Margidunum, near modern day Nottingham.

Here the Fosse has become the A46 and archaeologists working on a widening project uncovered a chilling mystery. A group of 20 burials, each containing the remains of a newborn or very young infants.

What could explain this grim discovery?

Cotswold Wessex Archaeology/Getty

Cotswold Wessex Archaeology/GettyAt this time infants had little or no legal status and could be abandoned by families without punishment.

"Where similar burials have been found, theories have centred around abortion and infanticide," says Dr Nik Cooke, who led the excavation team. "Certainly both were known in the Roman world."

One clue is they were found near a smithy and brewery, an industrial area, instead of being outside the settlement as decreed by Roman law.

"They were buried with care, possibly near a stone marker or shrine," Dr Cooke explains.

"The location might seem inappropriate to modern eyes, but both brewing and smithing are transformative processes, and likely held a degree of symbolism in Roman eyes.

"This is reinforced by the burial of the remains of a raven - a mystical bird ascribed supernatural powers by the Celts and Romans - within the floor of the smithy".

Might it be those burying the children hoped the transformative qualities of the smithy and brewery would renew the spirits of the dead infants?

It is a tantalising thought. While the exact status of the graves remains unclear, they are one of countless stories attached to the Fosse Way.

JHannan-Briggs

JHannan-BriggsFurther along the Fosse - in the guise of the the A46 - is the multicultural city of Leicester. It appears it may have been similar nearly 2,000 years ago.

"Among the discoveries here are skeletons with possible African ancestry and a curse tablet listing Greek-style names," says Mathew Morris, archaeologist and author.

"The Roman name - Ratae Corieltauvorum - was itself a hybrid, a native tribal name given a Latin polish."

But he says one object is particularly revealing.

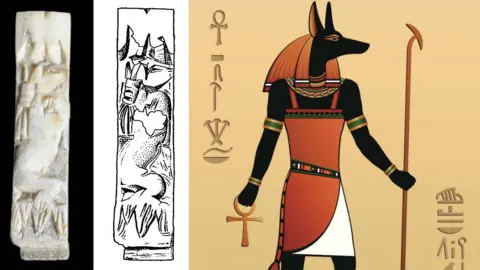

"This panel, perhaps from a box, is made of ivory and is carved with an image of the Egyptian dog-headed god Anubis.

University of Leicester/Getty

University of Leicester/Getty"This shows trade with the far corners of Empire, wealth, as this is an expensive item and perhaps an insight into the diverse religious life of the city".

While originally a military road, the Fosse became a vital trading route, with towns and huge villas spreading out from it across the landscape.

EH

EHBeyond Leicester the modern road diverts, leaving Fosse Way to byways and fields. But nearby may have been the bloody climax of events which rocked the Empire and put its new conquest in doubt.

An unremarkable cross roads at High Cross on the A5 is where Fosse Way meets another major Roman road - Watling Street. Close by, at Mancetter in Warwickshire, is one of the most likely places for Boudica's final battle.

After ambushing a Roman legion and burning three newly founded cities, the vengeful Queen's rebellion was shattered in a battle which became an orgy of killing.

Corinium museum

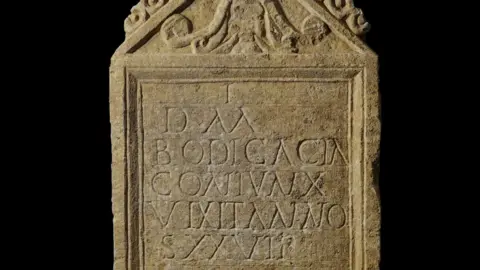

Corinium museumWith Rome triumphant, the inhabitants had to face life under the new regime and how this happened may be glimpsed in a tombstone discovered in Roman Britain's second largest city, Corinium, modern Cirencester.

Its careful inscription translates as "To the Shades of the Dead. Bodicacia, spouse, lived 27 years".

James Harris, collections officer at Corinium museum, says: "Bodicacia ending in 'a' is a female name.

"It's a Celtic name but on a high status Roman style memorial, decorated with a Roman god.

"The back of the stone is roughly worked so it was possibly originally set into the wall of a mausoleum, alongside the Fosse, a real statement of social achievement.

"Essentially Britain is the British peoples living a new Roman way of life under Roman rule, but they remain British."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut the large scale impact of imperial rule is shown by the next big settlement along Fosse Way - Bath, known to the Romans as Aqua Sulis.

"There was no local tradition of stone building so this must have looked like something dropped from outer space," says Neil Holbrook, of Cotswold Archaeology.

"And this was not a military site - it was recreation and leisure, a kind of Blackpool of its day.

"It also shows the way Rome tried to fit into its provinces. The centre was dedicated to Sulis Minerva, a mix of a classic Roman goddess and the local deity."

Mr Holbrook says: "While the Fosse started as a military road, it soon became a route for trade, communication and people and stayed that for the rest of Roman rule, another 350 years.

"And much of the original route, whether as country highway or busy truck road, does the same today."