Historical hazards of the home revealed

Leeds Museums

Leeds MuseumsExploding sweets, radioactive ornaments and poisonous medicine were just some of the potentially deadly dangers lurking in Victorian and Edwardian homes. These health hazards were often found in everyday, apparently innocuous objects.

Some of these items have - safely - gone on display in a Leeds museum. Here's a quick guide to the domestic dangers of yesteryear.

Household horrors

Leeds Museums

Leeds MuseumsThis glass table centrepiece contains uranium oxide, a radioactive compound that was added to some glassware in the 19th Century to give it a fashionable green tinge and help it stand out in the home.

Similarly, the streaky glass jug might look stylish but it too contains uranium oxide.

And this fire extinguisher, made in about 1910, might have been intended to make the home safer but early fire extinguishers such as this actually contained toxic chemicals that could be very harmful in confined spaces.

Leeds Museums

Leeds MuseumsThe feathered fan above contains a small stuffed bird. It might have been intended to beautify the fan but as Victorian taxidermists used arsenic or mercury as a preservative, this bird was dangerous to touch.

Leeds Museums

Leeds MuseumsAnd this dapper-looking top hat from 1840 contains mercuric nitrate, which was used to treat felt. The substance could cause heavy metal poisoning, which in turn could lead to aggression - hence the phrase "mad as a hatter".

Curator from Leeds Museums Kitty Ross says: "There were also whole ranks of toys that would not meet current regulations; choking hazards and sharp points were commonplace and many were covered in paint that contained lead, or indeed were made of lead."

Sweets, treats and smokes

Leeds Museums

Leeds MuseumsThese potassium chlorate pastilles were used in the 1880s to soothe sore throats - although as potassium chlorate could spontaneously combust, there was the danger that whoever took them might end up with a considerably sorer throat than before.

And this tin of lemonade powder, sold by Home & Colonial Stores, looks like it would mix with water rather nicely in the billy can next to it. Bad idea.

Enamel objects such the billy can often contained antimony, which could be dissolved by the acid in lemonade powder to create a toxic drink.

And sweets themselves could be deadly, as a mix-up in 1858 demonstrates.

A druggist's apprentice in Bradford accidentally supplied arsenic, instead of a sugar alternative, to a sweet-maker, who used the poison in the manufacture of a batch of humbugs.

About 20 people died and hundreds more suffered from arsenic poisoning.

Leeds Museums

Leeds MuseumsAnd we might all now be aware of the dangers of smoking, but this 1920s cigarette case bears the jaunty message: "When things are getting beyond a joke light a cigarette and have a smoke."

Potentially deadly advice, as science would later prove.

Powders and potions

Dr Stella Baraklianou

Dr Stella BaraklianouAs part of the exhibition, Stella Baraklianou is to deliver a talk entitled Potions and Powders: Beauty and Medications to Die For.

"You wouldn't believe it when you see some of the crazy concoctions that came from Victorian pharmacists, and after the medical industry began to patent and advertise products," she says.

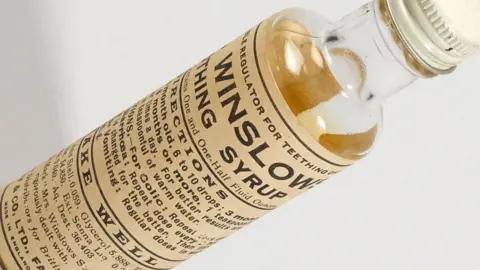

One concoction, Mrs Wilmslow's Soothing Syrup, contained morphine and yet was given to babies.

"It was meant to send them to sleep but some would never wake up," says Dr Baraklianou.

And laudanum, another staple of Victorian medicine, was tincture of opium containing morphine and codeine.

Sherlock Holmes, the famous fictional detective, was a user but so were many people in the real world, again including children.

What's more, many Victorian face powders contained arsenic, so a fashionable white complexion could be a killer.

"The powder would often cause facial scars... and so the user would use more powder to cover the scars," said Dr Baraklianou.

Prolonged use of such a product could prove fatal.

Leeds Museums

Leeds MuseumsAnd in the early 1900s, hair restorer - a liquid that was used on faded or grey hair - often contained both poisonous lead and combustible kerosene.

The home is now clearly a safer place, although as Ashley Martin from the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents points out, there's no room for complacency.

"Over the last 100 years there have been huge developments in public and environmental health and trading standards," he says.

"It is a constantly evolving progress but I'm sure there will be something today that at the moment doesn't seem to be a problem that could turn out to be a hazard."

Of course, it's not possible to make the home entirely safe - after all, one of the most dangerous things any of us does on a daily basis is to come down the stairs. About 6,000 people die in Britain every year in an accident in the home, Mr Martin says.

"There will be always something in the house that we need that is hazardous, like cleaning chemicals, but it is about how we store and use safely - it is not always the product itself."

Danger Zone opens on Saturday at Abbey House Museum in Kirkstall and runs for the rest of 2019.