Covid one year on: 'It's like a generation has gone' in Burnley

BBC

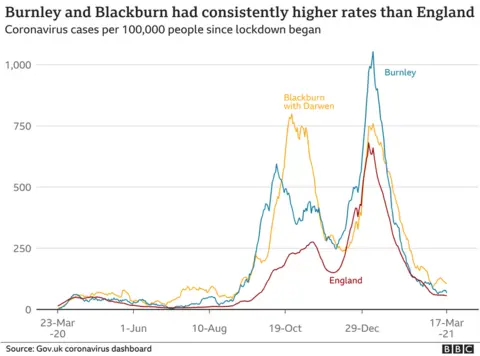

BBCThe Lancashire towns of Blackburn and Burnley have consistently had higher Covid-19 infection rates than the rest of England. But why?

"It's like a generation has gone," said Assad Waheed, reflecting on the impact of coronavirus in Burnley and on his own family.

Statistics often only seem real - painfully so - when they become deeply personal. When the daily death toll announced on the news includes somebody dear to you.

Assad lost his father in December.

Mian Abdul Waheed, 83, was one of thousands in the town to have contracted coronavirus. As of 5 March, some 305 people there had died with it.

"A good friend of mine lost his wife," Assad told the BBC. "So many people have lost their fathers. A neighbour of ours passed away recently, too."

Twelve miles to the west of Burnley is Blackburn. The East Lancashire towns may be bitterly divided when it comes to football, but they are joined at the hip when it comes to public health and the impact of coronavirus cases.

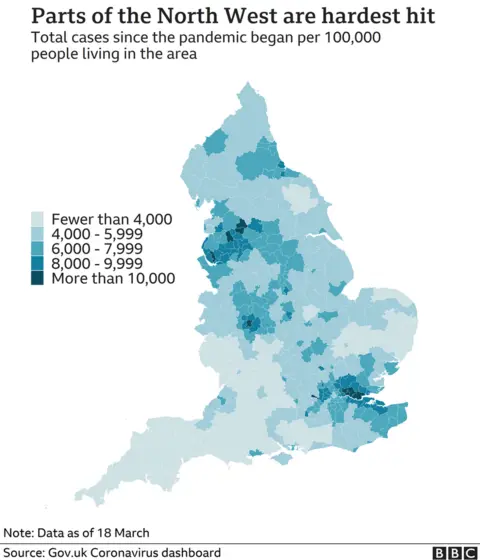

Blackburn with Darwen had the highest total cases per 100,000 people in England, while Burnley had the third highest, as of Monday this week.

Professor Dominic Harrison, Blackburn with Darwen Council's public health director, said the pandemic had highlighted inequalities that have existed for years in both areas.

This has meant they have had to "run faster and climb higher" than other parts of England to try to keep a lid on the infection rate.

Prof Harrison said local people went into the pandemic with higher than average levels of ill health and that this had increased their Covid-19 risk from the start.

More likely to need oxygen treatment in hospital, more likely to end up on a ventilator, more likely to die.

He passionately believes the government's current approach towards vaccinating the population largely by age groups is not just wrong, but "unfair, unjust and avoidable".

"It's a terrible error," he said. "If you live in the North West you have twice the risk of death from Covid so far in the pandemic and three times the transmission risk compared to somewhere like the South West."

A Department for Health and Social Care spokesman said: "From the outset we promised vaccines would be distributed equitably right across the country, and that is what is happening."

The North West has received several government interventions during the last 12 months.

Blackburn was one of the first places in England to be placed under tighter lockdown restrictions in July as the rest of the country, Leicester aside, began to enjoy the easing of the first nationwide lockdown.

Measures introduced in Blackburn included limiting household visits and requiring people to wear face coverings in enclosed public spaces, months ahead of the rest of England.

But despite this and further strengthening of restrictions a month later - this time forbidding households to mix at all - and yet more Lancashire-wide rules being brought in, infection rates have remained worryingly high.

In October, Burnley council leader Mark Townsend asked the government for stricter social contact restrictions in the town "before it was too late".

The whole of Lancashire was put into tier three restrictions later that month and moved to tier four in December.

Assad said his father was fit for his age and spent much of lockdown walking around his local park.

"He'd come back and say he'd done 10 laps round the tennis courts, he was an outdoor person," he remembers.

'Perfect storm'

But after testing positive for coronavirus, his 83-year-old dad was taken to hospital on 24 December and his condition deteriorated four days later.

"We got a phone call saying 'Listen he's not going to make it through, so if you want to come up and pay a visit to your father'," said Assad.

He said his father's death had left a "massive hole" in his heart, adding: "There is not a day that goes by where I don't feel his presence. He's dearly missed."

In February, a government report leaked to the Guardian concluded that places like Blackburn and Burnley faced a "perfect storm" of risk factors.

Deprivation was at the heart of everything, the report said.

Professor Harrison said a far greater proportion of people had been "exposed" to Covid in these east Lancashire towns than had been the case across England as a whole.

While many white-collar workers across the country were getting used to working from home, a lot of people in Burnley and Blackburn were "keeping us going in frontline roles: in transport, health and social care and retail".

He said these workers were more likely to be in "precarious employment" and on low incomes, meaning they could not afford to self-isolate.

Gannow Food Share in Burnley, which provides meals for struggling local families, said the number of households being helped had risen from about 30 last March to more than 500.

Project manager Tracey Noon agreed with the professor that a lack of money meant many people could not reduce their chances of catching or spreading the virus.

"We get a lot of people telling us they can't afford to be on sick pay," she said. "We get a lot of people telling us they are already on low-paid jobs."

Jonathan Adamson, who uses the Food Share after losing his job in Burnley at Christmas, contracted Covid-19 along with his partner.

He said many people in the area continued to work despite having symptoms.

In a previous job he said he had often seen "sick people walking around".

"You could see how run down they were or tired and then it turns out them people that I've seen have actually contracted Covid," he said.

Prof Harrison said other risks which have led to higher cases in East Lancashire included cramped housing and ethnicity.

A June 2020 study by Public Health England found Covid death rates were highest among people of Black and Asian ethnic groups.

About 45,500 people in Blackburn, 31% of the population, are from a BAME background while in Burnley, about 11,000 people or 12% of the town's residents have a similar heritage. In England it is about 13%.

As England prepares to ease lockdown measures, Prof Harrison said he was "very worried".

He thinks Blackburn with Darwen, Burnley and also nearby Pendle are still vulnerable.

"All those risks which drove high rates last year remain unchanged," he warned.

When schools returned to classroom-based learning on 8 March he said Blackburn with Darwen had 112 cases per 100,000 people, compared to an average of 65 in England.

"We are already starting at a higher risk," Prof Harrison said.

The latest data showed there was a slight rise in cases in the week after schools returned - but infections have since fallen.

In the week to 18 March, 153 cases were recorded, a drop of 21% on the previous week.

Prof Harrison said: "We have to run faster and climb a higher hill to achieve the same that everybody else is going to [do in] keeping the risk down."

Why not follow BBC North West on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram? You can also send story ideas to [email protected]