Normandy veterans' welfare officer makes good a lifelong promise

BBC

BBCAged 90, "welfare officer" Ernie Lornie continues to look after the few remaining D-Day veterans and their families, honouring a pledge he made to them years ago. BBC News' Kevin Shoesmith went along to see him.

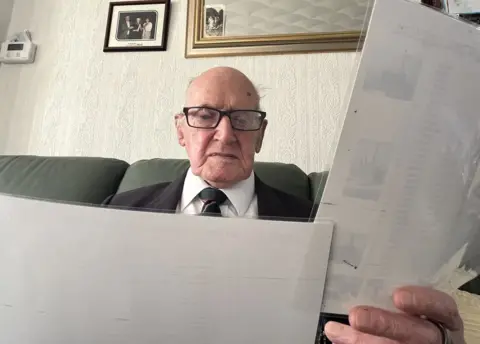

Ernie Lornie flicks through the pages of a photograph album, the front adorned with faded poppies.

The 90-year-old smiles at old friends on the sweeping beaches of Normandy that pulled them back year after year.

"Come on, lads - where are you?" he whispers, scouring the album for two Hull D-Day veterans among the dozens eyeing us from within their polythene pockets, each image numbered.

MoD

MoDIt is hard to fathom, almost, but on 6 June 1944 - D-Day - this nonagenarian was too young to have played a part in World War Two.

For 25 years, though, Ernie has been an honorary memory of the Normandy Veterans' Association, serving as their "welfare officer".

It is a role he continues to take seriously, ensuring the few remaining veterans, as well as their widows and children, are cared for.

"I can imagine all those lads looking down at us now laughing and saying, 'what are you saying about us, Ernie?" he says.

Despite settling in East Yorkshire after leaving the Merchant Navy in 1962, Ernie retains his Aberdeenshire accent.

A tartan cap, a nod to his Celtic roots, sits next to him on the sofa in his living room, at home in Hessle. A child's drawing, sketched by his great-daughter, is fastened to the wall above the fireplace, drawing us back into the present.

Ernie hands me two lists containing the names and addresses of 61 Normandy veterans.

"Only two are still with us," he says, pointing them out. "Only two."

New families will have moved into these homes, oblivious to the lives forged from sacrifices made in sand.

"But these lads' families are still with us, and I made a promise to look after them," says Ernie, now looking me in the eye.

Right there, is his raison d'etre.

Placing the lists down, Ernie adds: "I hope the veterans would be happy that I'm doing this because I made that promise, and I am one of those types of people that when I make that promise I see it through."

Until now, Ernie has batted away offers to tell his story about his connection with the D-Day veterans, preferring instead to keep the focus on the Normandy veterans.

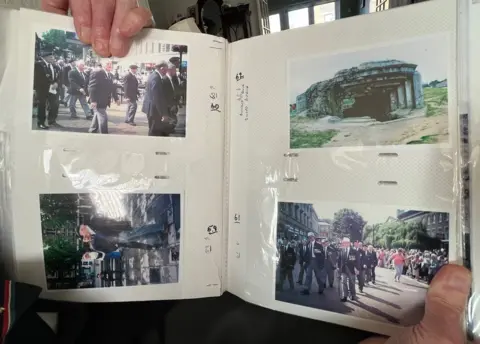

For years, he has stood in the background, accompanying veterans on pilgrimages back to the landing grounds, where so many of their friends made the ultimate sacrifice, and to military parades across the country.

Mike Fuller

Mike FullerHe has stood, watching as French crowds - including the young brought up knowing their history - surrounded them, requesting photographs, and smiled as bartenders refused to take their money.

Close to tears, Ernie says: "To me, they are gentleman heroes and you cannae get any higher than that."

Ernie casts his mind back to the many conversations he had with D-Day veterans. On long coach trips to Normandy. At their homes. In hospital.

"In their mind, I know they were thinking, on those beaches, 'will I be here tomorrow?' But they kept going, knowing they had a job to do," says Ernie.

"They were not thinking of themselves. They were thinking of their families, their country. They should never be forgotten."

And neither should their families, he insists.

"I ring them on a Saturday or Sunday each week," says Ernie. "Just to make sure they're OK and to see if they need anything."

Ernie's link with the Normandy veterans began in the 1990s. His daughter Marion married Alyn Ainsworth, the son of John Ainsworth, a D-Day veteran who became chairman of the Hull branch of the Normandy Veterans' Association.

Ernie recalls: "One day, John said to me, 'why don't you come down one Sunday and join us?' That was when they met at the Railway Social Club on Anlaby Road in Hull.

"When they accepted me, I felt so proud.

"If anyone missed one of the branch meetings, I'd give them a ring to make sure they were OK. I'd never push, but if they wanted me to visit, then I'd go and visit them."

Born in 1932, Ernie's formative years had been consumed by war. He had seen bombing raids, lines of tracer fire slicing into enemy bombers, and had even set foot on a captured German U-boat in 1945.

In addition, he had seen his two older brothers, David and Alex, return from active service in Europe and the Far East, respectively.

Ernie explained that he felt a debt towards veterans.

"When the branch's welfare officer - a Normandy original - died, we were all asked if we wanted to take on the role," says Ernie.

"I stood up and said I'm not a true Normandy veteran but if you would allow me I'd like to do it. I've been the welfare officer ever since."

Ernie lost his wife of 61 years, Valerie, in December 2018. He apologises for the lack of detail over dates, insisting, with a smile, his wife - also treasured by the Normandy veterans - would have had them at her fingertips.

But he soldiers on.

"There they are," he says, his index finger hovering over a photograph of John Ainsworth and Ray Lord. Both are now at rest. Old warriors stood down.

Ernie adds: "As I said to these lads, and all of the others when they were alive, I will be the last person to turn the lights out."

Follow BBC East Yorkshire and Lincolnshire on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].