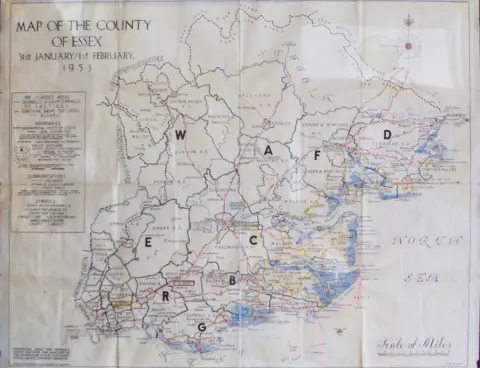

Flood of 1953: Canvey Island defiant in face of rising sea levels

Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive

Courtesy of Canvey Community ArchiveSeventy years ago, a freak blend of weather events caused one of the worst natural disasters in British peacetime history. The 1953 North Sea floods killed 307 people and deluged 24,000 homes along the east coast. The tragedy has defined sea defence strategy ever since - but for how much longer can these low-lying communities be protected?

People on the Norfolk coast had already drowned, or were cowering on rooftops, when parents on Canvey Island were tucking their children into bed - blissfully ignorant - on the evening of Saturday, 31 January, 1953.

Cyclonic southerly winds were still a few hours north of estuary Essex.

Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive

Courtesy of Canvey Community ArchiveJoan Liddiard (née Bishop) remembers how, as a six-year-old, she clambered into the loft of the family bungalow in the middle of the night with 27 relatives and neighbours.

The water level had reached about 4ft (1.2m) and was seeping into her two-year-old sister's cot.

She recalls her uncle defiantly playing piano through the night downstairs - water presumably lapping at the keys - while the huddled family sang upstairs.

Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive

Courtesy of Canvey Community ArchiveBy morning, the water had settled to ankle depth and her mother fried bacon and eggs on the stove.

Joan was sent to stay with distant family friends in Leytonstone where she was fussed over in the playground and was showered with sweets and toys by other children.

"It was kind of an adventure because we didn't really know the full impact," said Joan, now 76.

"I came back here about six weeks later and I think it was then that the devastation hit me."

Peter Walker/BBC

Peter Walker/BBCHer classmate Ian Nelson drowned and his body, along with the dog lead he was holding, was found 10 days later.

Four-year-old Judith Goodman, who was huddled with her family on a rooftop for 12 hours wearing nothing but her night dress, died from hypothermia.

The sea had cascaded over the dykes on the eastern side of the island and 8ft (2.4m) waves ripped bungalows from their foundations.

Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive

Courtesy of Canvey Community ArchiveGraham Stevens laughs remembering his father piggybacking him and his siblings away from their home, and ferrying away the family dog in the bath.

"I was never scared, not initially, but at one point when we were upstairs, it suddenly occurred to me I could hear wailing outside," said Graham, who was 10 years old at the time.

"I suddenly had the realisation that there was something a bit more serious."

Rod Bishop, Joan's cousin, who was nine when the floods struck, said: "I will always remember, as I came out of our gate, hearing screams and shouts from the other side of the island."

His father, the local greengrocer, helped identify the bodies of his customers, including an elderly couple found prised together.

Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive

Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive Peter Walker/BBC

Peter Walker/BBC Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive

Courtesy of Canvey Community ArchiveThe hurricane winds, combined with a spring tide and a full moon, killed 59 people on Canvey.

Non-existent lines of communication meant news did not travel from Hunstanton in Norfolk, where 31 people died, or from Felixstowe in Suffolk where 41 were killed or from Jaywick in north Essex, where 35 perished.

In the Netherlands, more than 1,800 people died as well as 187,000 poultry and cattle.

Peter Walker/BBC

Peter Walker/BBCNew sea walls at Canvey, and two flood barriers, were built in the 1970s.

Contractors are on site rebuilding and reinforcing those same walls with structures expected to last until 2070.

Further reinforcement is in the offing at Jaywick and Felixstowe, while plans for the UK's second largest tidal surge barrier are being drawn up for Lowestoft in Suffolk.

Tides exceeded the levels of 1953 at various spots along the coast in 2013 but caused far less destruction and no fatalities.

Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive

Courtesy of Canvey Community Archive"There will be a similar event at some time in the future but we don't quite know when," said Mark Johnson, area coastal manager at the Environment Agency.

"That's why we forecast and we work closely with our partner organisations if weather patterns are developing."

Canvey, along with so much of East Anglia's coastline, is projected to be below annual flood levels in 2050.

The town's ground level is already about 6.5ft (2m) below the daily high tide in the Thames.

According to Met Office projections, under an optimistic "low emissions" scenario, the Thames will be 2.2m higher in 2300.

"You can't really defend the Netherlands with that amount of sea level rise - forget Canvey," said Prof Martin Siegert, a glaciologist who grew up in Suffolk.

"You can't defend that with a sea wall, unless you build it really high and that's a huge expenditure.

"If you just increase the level of the ocean by a few metres you have to ask the question, literally, is it worth the expense of putting that sea protection in? Is that protection forever or is it just a stopgap?

"If I was in Canvey I would be very concerned about the future, as many low lying islands would be, and I wouldn't be in denial about it."

Jules Pretty, who chairs the Essex Climate Action Commission, believes the projections can be avoided.

"I am optimistic that we can avoid the worst of outcomes from the climate crisis - but this does need us to get to zero emissions as soon as we can," said Prof Pretty.

Martin Siegert

Martin Siegert Climate Central/Google

Climate Central/GoogleRod, Graham and Joan are proudly and unwaveringly optimistic about Canvey's future - and whether it has a future - partly because they have witnessed the alternative.

"I personally don't think so," said Rod, asked if he can imagine Canvey being uninhabitable in 200 years' time.

"The sea defences we've got now will be improved in the future, I would think, and would stop anything like that happening.

"Canvey will be here forever."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesRay Howard MBE, who was 10 when his sister woke him that night, has been at the forefront of flood defence planning for the island.

"Despite that terrible event, on that terrible night, that caused devastation - I do believe that Canvey now can sing because we have billions of pounds of investment on this island," he said.

"I do believe that Canvey is now thoroughly protected.

"I can't see it [going under water], I just can't - but you never know."

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. If you have a story suggestion email [email protected]