Ammonite: Who was the real Mary Anning?

See Saw Films / Lionsgate Films

See Saw Films / Lionsgate FilmsA story about a self-taught palaeontologist called Mary Anning has been transformed to the big screen as Ammonite, a depiction of a 19th-century love affair.

Francis Lee, who wrote and directed the film starring Kate Winslet and Saoirse Ronan, readily admits this is not a biopic - and stands by the decision to depict a same-sex love story, despite the fact that Anning's romantic inclinations are lost to history.

What is known about Anning - who helped shape our understanding of prehistoric life - makes it clear why her story inspired Ammonite, which has its UK premiere on Saturday.

"Mary Anning was three things you didn't want to be in 19th-century Britain - she was female, working class and poor," says Anya Pearson, who is campaigning for a statue in her honour.

"This was a time when even educated women weren't allowed to own property or vote, but despite this horrendous upbringing she was able to do all these incredible things."

NHM

NHMAnning's life was scarred by hardship and tragedy but also punctuated by scientific firsts.

She regularly risked her life in her hunt for fossils, making discoveries that captured the attention of the scientific elite, even though her social status and gender meant she never received the credit she deserved.

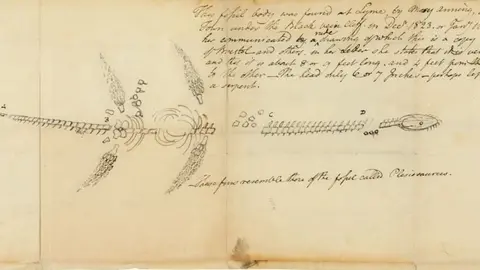

In 1811, at the age of just 12, Mary discovered a 5.2m (17ft) skeleton, now known to be an ichthyosaur. Twelve years later, she found the first complete skeleton of a plesiosaur, a marine reptile so bizarre that scientists thought it was a fake.

She also unearthed the UK's first known remains of a pterosaur, believed to be the largest-ever flying animal.

NHM

NHMAnning was born on 21 May 1799 in Lyme Regis, Dorset. She had been one of 10 children but they were a poor family and eight of her nine siblings died before reaching adulthood.

As a child, she would help her father collect fossils that he sold in his seafront cabinetmaker's shop but in 1810, when Anning was 11, he died of tuberculosis. After his death, to help her mother make ends meet, Anning continued to collect fossils she would sell to tourists and collectors.

"Mary Anning had very little formal education," says Emma Bernard, the Natural History Museum's curator of fossil fish.

"However, she did educate herself on geology and anatomy and would dissect modern animals like fish and cuttlefish to better understand the fossils she found."

NHM

NHMIt was a year after her father's death that Anning discovered the skeleton - now known to be an ichthyosaur - that helped propel her into the history books.

At the time, the notion of extinction was a relatively new idea to science and the otherworldly creature became a topic of debate for many years.

Lyme Regis Museum geologist Paddy Howe, who was a technical adviser for Ammonite, describes Anning as a "very poor child who was making fantastic scientific discoveries".

"At this time, geology and palaeontology were burgeoning sciences - just coming into their own, he says. "We know about ichthyosaur bones from the 1600s but it was the first one to be studied by scientists. It was very important."

NHM

NHMThe marine reptile was bought from Anning for £23 and then purchased by the British Museum at auction in 1819. It can still be seen at the Natural History Museum today.

In 1823, 12 years after her ichthyosaur discovery, Anning became the first person to unearth a complete skeleton of another prehistoric sea creature - the plesiosaur.

"This particular specimen is the holotype, which means it is the specimen used to describe this species and that scientists still refer to it today when studying plesiosaurs," Ms Bernard says.

"It was after this that scientists started to take her finds more seriously, seeking her out to look at her discoveries and discuss ideas."

NHM

NHMDespite Anning's growing reputation, societal norms meant she would never be accepted into the elite scientific community. In fact, when the Geological Society met to discuss whether the plesiosaur was genuine, she was not invited - women were not admitted there until the 20th Century.

"If she was born in 1970, she'd be heading up a palaeontology department at Imperial or Cambridge," says David Tucker, director of Lyme Regis museum.

"But she was a commercial fossil hunter; she had to sell what she found. Therefore, the fossils tended to be credited to museums in the name of the rich man that paid for them, rather than the poor woman who found them.

"This isn't just around gender - the history of science is littered with the neglected contributions of working-class scientists."

Neil Bigwood

Neil BigwoodDespite her lifetime of groundbreaking work, Anning remained in hardship and died of breast cancer in 1847, aged 47. She is buried at St Michael the Archangel Church in Lyme Regis.

Following her death, Henry De la Beche, president of the Geological Society and a friend of Anning, broke with the society's members-only tradition to read a eulogy at a meeting, paying homage to her achievements.

He wrote: "I cannot close this notice of our losses by death without adverting to that of one, who though not placed among even the easier classes of society, but one who had to earn her daily bread by her labour, yet contributed by her talents and untiring researches in no small degree to our knowledge."

Three years later, a stained-glass window in her memory, paid for by members of the Geological Society, was installed in the church where she was buried.

Chris Talbot

Chris TalbotHer legacy is also marked at Lyme Regis Museum, where there is a gallery dedicated to Anning's life. In a pleasing coincidence, the museum stands on the site of her birthplace and family home.

"The fact that the museum is on the site of Mary's house was not in any way planned," Mr Tucker says. "Her family rented a part of the house which stood where we are, right on the edge of the sea.

"They were living in a house that was on the way down and prone to being hit by the huge waves and it was eventually destroyed by a storm."

See-Saw Films / Lionsgate Films

See-Saw Films / Lionsgate FilmsMore than 170 years after her death, Anning's story is taught in schools, and a campaign, supported by Sir David Attenborough and Prof Alice Roberts, is under way to erect a statue in her honour.

Evie Swire, 13, began campaigning for the statue two years ago, claiming there were more statues in the UK of men called John than there were of all women.

"She's done all these amazing things and sadly has been lost in history," Evie says.

Her Mary Anning Rocks project recently selected sculptor Denise Dutton to create the statue, which would be erected on the seafront. A crowdfunding appeal to fund it will be launched next month.

"There have been a lot of forgotten women in history but all of them were educated and came from a wealthy background, but she was poor and working class," says Evie's mother and campaign trustee Anya Pearson.

"I get angry when people refer to her as 'just a fossil collector' because she had great men of learning travel across Europe to learn from her.

"I think she's a wonderful, inspirational role model for kids today."

Ammonite's UK premiere takes place at the BFI London Film festival on Saturday. A special preview screening of the film, with introductions from the director and the cast, is also being shown at cinemas across the UK on the same day.