'I found out I was HIV-positive at 12 years old'

@captain.frost

@captain.frostAloma Watson-Ratcliffe was 12 years old when she found out she had contracted HIV from her mum. Now 20, she describes what it was like to deal with the condition as a child and how she learned to cope with the fear and stigma.

I got HIV from my mum Molly - I was diagnosed at three years old. We don't know for sure how I got it but I had a natural birth which was un-traumatic, and because of this, it is highly unlikely transmission happened until breast feeding.

Mum knew she was HIV-positive and had done for quite a few years. She got it from an abusive partner in her 20s. She wasn't dying, she was healthy, and that was what she wanted for me.

Family picture

Family pictureBreastfeeding is a really bonding thing - it's a choice every mother has to make for themselves and I respect my mum's choice. She had been advised by doctors not to breastfeed at all and had been told that I should take medication, but both of my parents decided it would be really bad for me to start taking the [antiretroviral] drugs as an infant.

They decided it was better that I build up my natural immunity and... kids were having bad side effects. Friends of mine who were given [the drugs] all have messed up systems and different allergies or medical conditions. I have a very strong immune system so I think it was a really responsible choice [not to be given them].

Aloma Watson-Ratcliffe

Aloma Watson-Ratcliffe We had moved from London to Melbourne when I was very young. My mum went through various stages of being ill - she would get better for a time and then it would spiral. She died in October 2001 and six months later, when I was three, we moved to Totnes in Devon and I was diagnosed as HIV-positive.

I had regular blood tests in London to monitor the progress of the virus every three months. The [doctors] would explain the results [using] animations, but they didn't give it a name. I knew there was something different about me. I had the same childhood illnesses as anyone else but I would get bruises - not painful, just starkly visible - and they would take a while to go away.

I was 12 when the doctor told me I was HIV-positive. I remember being really scared and feeling like I was going to die. You hear about HIV and Aids in the playground; the dirty jokes, about Aids coming from monkeys. I already had this idea in my head that it was kind of a death sentence.

Children and HIV

- There are about 530 HIV-positive children and young people under 18 in the UK

- There were 4,500 pregnancies to HIV-positive women in the UK and Ireland between 2015 and 2018

- Of those, 0.3% transmit the virus to their children, either through pregnancy, birth or through breastfeeding

- Taking antiretroviral treatment correctly during pregnancy and breastfeeding can virtually eliminate the risk of passing on the virus to the baby

Source: National Surveillance of HIV in Pregnancy and Childhood/Public Health England/Avert

I tried to keep it together and act really mature but my feelings around it were of fear and I didn't know anyone who had HIV. I was alone and that was quite a weight. It was a horrible secret that I didn't understand. It made me a very closed child, with a lot of social issues.

Some parents found out through teachers, or other parents. They would approach my dad kind of in hysterics and ask, "why are you just letting her run around and drink the same water as us?" If I tell a friend, one of their first questions is, "Is it safe to to drink the same water?" It's not transmitted by saliva but for some reason that's a myth that's really hard to get rid of.

Teachers would come up to me out of the blue and be all pitying - they would ask me, "how are you getting on with our medication?" And I was like, "It's none of your business".

Aloma Watson-Ratcliffe

Aloma Watson-Ratcliffe

At 15 I saw a therapist/counsellor for other reasons and I told her and started to cope with it. Then [the following year] my step-mum heard about the Children's HIV Association (Chiva) camp on the radio. It's for 100 young people who have HIV and for five days you get to learn [about the disease] and sex education and do fun things.

I was terrified to go. I didn't know it was going to be this life-changing thing but it really was. It was the first time in my life that we were able to say "HIV" all the time. The volunteers would constantly say it, we all had it and it was not scary.

We could talk about medication and side effects; we could talk about jokes that we had heard in the playground and we could laugh about them.

It was an incredibly important [experience] because the rest of the world doesn't feel safe - in the playground you don't feel safe; in relationships you don't feel safe until you've told them and you work out their reaction. Some people don't feel safe in their families because [of the] stigma about it. So being safe and happy is unusual and important.

Toni Watson

Toni WatsonChildren and antiretroviral drugs

Aloma was given HIV medication at the age of 11, the year before she was told she had HIV.

The NHS says treatment can be started at any point following diagnosis, "depending on your circumstances and in consultation with your HIV doctor".

Amanda Williams, consultant paediatrician and chairwoman of Chiva, said: "There's been a changing picture in research around HIV and a huge change in the drugs available and evidence about the best time to treat children.

"Because of trials we know the side effects and the benefits of drugs more clearly now than 20 years ago when parents then would have been less sure about the side effects than they are now. Some people's belief systems are very strong and it's very difficult for those families to accept medication.

"It's always been the case that any child who shows symptoms and whose immune system has been dropping would have been treated. But there have always been differences where families are not keen on medication because of their beliefs about health and the stigma."

@captain.frost

@captain.frostI take one tablet a day. It keeps [the virus] dormant in my body. It's in my blood but it's not able to mutate. Some people get depression, throw up all the time or they can't eat, it can be a real struggle. For me I haven't had bad side effects, so I will continue to take it.

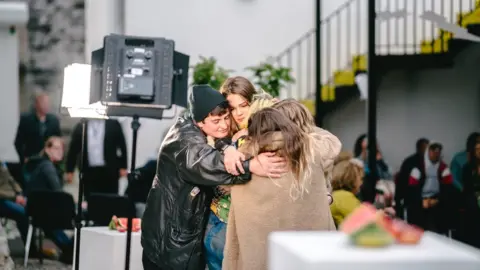

HIV does not mean that you're a dangerous person - that's why I created a performance about it, which I recently staged at the School of Art in Plymouth, where I have been a student. When I finished, there was a really long silence then everyone was clapping and people were crying. We had this really big group hug.

You might also be interested in

I think there's been an improvement in attitude but there is still a lack of education in schools about HIV. It's not really covered in sex education, it's only covered as a sexually transmitted disease, which is not how I got it.

It's always challenging telling partners, often the conversation is around passing it on and safety. Most of my previous partners have not had a problem with my status once it's been discussed in depth.

Even though I am public about my status, when I care about how someone could react it doesn't matter how much practice I get because it will still be emotional.

I'm seeing someone at the moment and they are perfectly fine with it, so long as we can be honest and they can ask me about any fears or questions, it works.

As told to Jonathan Morris

The following organisations can provide help and support for people with HIV.