Inside the 'town' behind Sellafield's security fence

Sellafield Ltd

Sellafield LtdSellafield is one of the largest nuclear sites in Europe and with 11,000 people working in 1,300 buildings connected by 25 miles (40km) of roads across 700 acres (283 hectares), is comparable in size to a small town. The BBC spoke to four people who help keep the £2bn-a-year operation going.

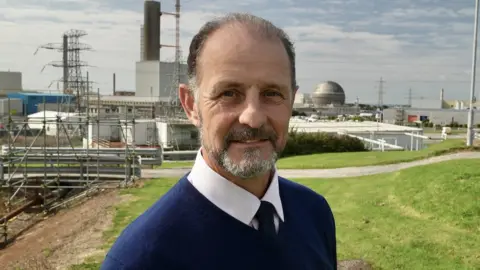

The security chief

The Sellafield compound stands on the shore of the Irish Sea and in the shadow of the Lake District, behind mile upon mile of impenetrable fencing.

Within the dense network of buildings, pipes and pylons is a small mound of greenery.

From there, Mark Neate can see the past, present and future of Britain's foray into nuclear research, development and power.

To the left are the four dormant reactor buildings and turbine halls of Calder Hall nuclear power station, long strands of foliage sprouting from the roofs.

To the right is the "golf ball", a giant orb that housed an experimental gas-cooled reactor, and, slowly being dismantled, the last of the two concrete towers of the Windscale Piles where plutonium was first produced in the 1950s.

In between are hundreds of buildings, anonymous, windowless warehouses, enormous ponds of vivid blue water containing submerged nuclear waste, brick office blocks and temporary cabins used for the never-ending construction of high-security storage facilities.

Sellafield has its own transport system of shuttle buses, canteens, laundries, security staff, armed police, firefighters and a medical centre.

As director of environment, safety and security, Mr Neate is responsible for keeping it all safe.

"Our dominant mission is high-hazard risk reduction," the former soldier says, adding it is a mission that will outlive him and continue for at least another 100 years.

Most activity here is dealing with the legacy of the site - cleaning up, repackaging and storing the nuclear waste generated over previous decades.

The ponds and silos where nuclear materials were stored are classed as four of the most high risk nuclear sites in Europe, so security is naturally very tight.

Security teams guard the gates, checking passes and vetting vehicles before they can enter the compound, while the armed Civil Nuclear Constabulary patrol within the fences.

Protection is further layered, with access to certain buildings only authorised to those with the highest level of clearance.

Even though he is the security boss and can, in theory, enter any part of the site, Mark still has to have a good reason to do so in some quarters and must be accompanied by an expert in "nuclear safety".

"Security starts with every individual on site," Mark says. "Like any town or industry we are challenged by conventional health and safety issues, but then we have got the nuclear challenge as well."

He is proud of Sellafield's strong security record, adding regular site-wide drills based on various scenarios including terrorism are carried out.

For a man with an awesome responsibility - "if we sneeze here the whole industry gets a cold" - Mark is very cheery.

"I do see it as fun," he says.

The firefighter

Sellafield is a "friendly community" according to firefighter Macy Barker and like any settlement it needs a fire brigade.

There are always at least 16 firefighters on duty, ready to respond to fires, chemical spills, traffic collisions or medical incidents as they also double as the site's ambulance crew.

"We go through the usual training to be a firefighter, but then we have to learn some extra stuff here," Macy says.

The 22-year-old from Silloth, Cumbria, has worked at the site for four years having completed an apprenticeship with the Sellafield brigade.

Firefighting is in her family and although she never planned to join up, she realised one day how happy her relatives were in their jobs.

She initially found Sellafield "a bit strange" given its high-security status and the knowledge of what it contained, but once inside the compound it became "like a community and it's a very friendly place".

The crews require an extensive knowledge of every building on the site, including the layouts and hazards, so they can ensure any incident can be quickly dealt with before becoming a major emergency.

They need to know how to reach the highest roof tops and smallest corners and how to move in protective radiation gear. Regular training and drills are a necessity.

Every building is fitted with an automatic alarm to contact the fire brigade in an emergency, with the crew able to be at any point of the densely packed site within minutes.

The Sellafield crews work closely with Cumbria Fire and Rescue Service and do leave the site to assist their colleagues, while always maintaining a core of personnel at base.

Similarly, the Cumbria firefighters can be drafted into Sellafield if needed.

Macy won't be drawn on the particulars of any incidents she has responded to, but says simply: "Every day is different."

The doctor

At first glance Russell Newlove's office looks like any doctor's surgery, there is the usual paraphernalia, a desk, an examination bed, a privacy curtain and drawings by his children.

However, the library of reference books crammed along his window sill - including The Medical Management of Radiation Accidents - reveals this is no ordinary clinic.

Dr Newlove, sporting eye-catching novelty socks with a dark suit, works in the medical unit at Sellafield, predominantly in an occupational health role.

He and a team of nurses perform regular medical tasks for staff, from checking blood pressures to looking for the effects of ionising radiation.

"The number of hazards and risks are huge but safety is always the priority," he says.

They range from the usual issues of noise and vibrations from tools and machinery up to chemicals and ionising radiation.

"I do enjoy it. The variety of work is good," he says.

The unit also deals with minor medical issues in a "first aid role" but anything serious will see patients taken by ambulance to the hospital at Whitehaven, although such incidents are rare, according to Dr Newlove.

Nurses are on site 24 hours a day, seven days a week, while doctors are on call overnight for "radiological emergencies".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSellafield's medical staff have to undergo extensive training around radiation "so we can keep up to speed with correct management of patients", Dr Newlove says.

As well as seeing people in his office, Dr Newlove also goes into the buildings, some of which contain the most highly radioactive materials imaginable, to observe workers in situ.

"The high hazard areas are there but the way risk assessments are done is to make it as safe as possible," he says. "The people that work here are highly skilled at what they do.

"Coming from the NHS, a lot of things that happen here are quite eye-opening, not the sort of thing you normally see."

The apprentice electrician

Born and raised 12 miles up the coast in Whitehaven, Charlotte Chan had always known of the large nuclear facility on her doorstep.

"It was kind of scary," she says. "Before you come here you are thinking about the radiation but once you are in it's not so bad."

Charlotte has been "in" for a couple of years having switched from a career in dentistry to become an apprentice electrical and instrument worker.

"I wanted to do something different and a bit more hands on," she says, although she admits she was "not really interested in science" at school.

There are different types of radiation monitors, the most common being a badge worn on the breast that records exposure to radioactive materials.

"You have to be careful around contamination but that is why we have all these procedures," Charlotte says.

She won an award for "going the extra mile" during her apprenticeship in 2020 and says she is enjoying her time on the site.

"It's not like how I imagined," Charlotte says, adding: "It's actually a lot larger than I thought.

"Everyone is really nice and made me feel welcome.

"It's just like a big town."

Follow BBC North East & Cumbria on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected].