St Ives lifeboat disaster: Coxswain pays tribute to 'selfless' crew

Jack Lowe/ St Ives Museum

Jack Lowe/ St Ives MuseumA lifeboatman has paid tribute to the "selfless" crew who died in a disaster 80 years ago.

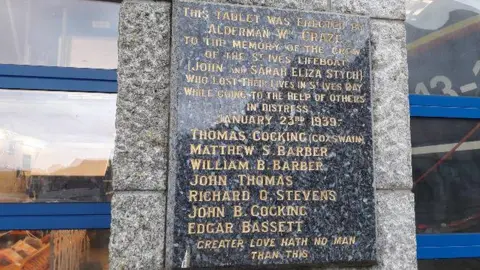

Rob Cocking's great-great-grandfather Thomas and great-uncle John were among seven men killed in the St Ives lifeboat disaster on 23 January 1939.

Mr Cocking, who is the St Ives crew's current coxswain, said the men who died should "be remembered always for what they gave and sacrificed that night".

A memorial service is being held in the Cornish town to remember the victims.

"These men were local St Ives men, they went out in the most appalling weather conditions regardless of what could happen and what the outcome would be," Mr Cocking said.

"They went out to save the lives of others - and in doing so tragically and selflessly lost their own lives.

"I know that I will always remember what they gave and I hope, as time goes on, we always take time to remember the ultimate sacrifice."

Jack Lowe

Jack Lowe

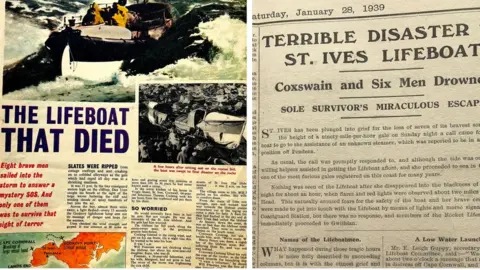

The night the lifeboat died

St Ives Museum

St Ives MuseumOn a fierce, stormy night a maroon flare went up shortly after midnight, the familiar signal to the lifeboat crew of St Ives that they should head down to the station.

A large steamship had been spotted in distress, toiling in north-westerly gales of up to 100mph, two miles off Cape Cornwall to the west.

It took three hours for the John and Sarah Eliza Stych lifeboat to be readied and then pulled down the streets and through the surf by 80 people.

She was launched into the teeth of the violent storm at about 03:00 with eight crew members on board. Just one would return.

St Ives Museum

St Ives MuseumLed by coxswain Thomas Cocking, the open topped boat struggled in the rough seas and soon got into difficulty when a huge wave knocked six of the men overboard.

Two clambered back on board when she self-righted but four, including the coxswain, vanished into the raging sea.

St Ives Museum

St Ives MuseumWith the sail in tatters, the motor no longer engaged and the crew halved, they attempted to drop anchor and ride the storm but the cable snapped.

Townsfolk watching from the headland saw a flare go up from the lifeboat, a sinister message glowing in the early morning sky that their friends, husbands, brothers, sons and grandsons were in grave danger.

As the ferocious conditions swept the boat across St Ives bay, another wave smashed into it causing the craft to overturn, accounting for another crew member.

The three remaining men pressed on and after yet another capsize, the vessel self-righted once more but this time washed on to rocks not far from Godrevy lighthouse.

'It is with you forever'

St Ives Community TV

St Ives Community TVVera Care, who still lives in St Ives, was 12 when her fisherman father, William Barber, 37, was called out to man the lifeboat.

"It's very vivid, as if it happened last weekend. I remember it was a terrible night, well over 100mph wind.

"My mother said to my father 'you aren't going out on a night like this' but he said 'it's my duty' and off he went.

"I was with my mother and my brother in our house on Teetotal Street - I had a feeling he wouldn't come back. You can't explain that night and the winds.

"My father's body was recovered two days later. It seemed unreal. It was a very small community in those days. It was a town of mourning and it was a terrible, terrible time.

"It is with you forever. It crippled my mother, it ended her life really. She said she had to start another life afterwards."

St Ives Museum

St Ives MuseumWilliam Freeman was the only man left with the boat, and the only survivor. Incredibly it was the first time he had ever been on the lifeboat, having volunteered on the quayside when the crew was one short.

Exhausted, he fought his way over rocks and up the beach to a cliff-top farm where he was offered shelter while the farmer cycled into town to deliver the news about the lifeboat's fate.

Mr Freeman died on 23 January 1979 - the 40th anniversary of the tragedy - and it was said he never again set foot on a boat.

St Ives Museum

St Ives MuseumThe day after the tragedy, the remains of the SS Wilton was found wrecked on nearby rocks with no survivors from a crew of 30.

The John and Sarah Eliza Stych was on loan from Padstow, as the St Ives station had lost its previous boat the year before when it responded to a cruiser Alba that was wrecked off the town.

All eight crew members were awarded the bronze medal for gallantry by the RNLI later that year - for seven of them the award was posthumous.

The Cocking family of St Ives is intrinsically linked to the town's lifeboat station.

Rob Cocking's father Thomas was also coxswain between 1967 and 1989, and his brother, Tommy, filled the role between 2000 and 2011.

Rob Cocking, who became coxswain in October 2015, said: "I wasn't ever not going to be involved with the lifeboat.

"I was raised around it and that, along with the sea, has always been a part of my mine and my family's life from boy to man.

"I was driven to be a part of this and knew in my mind that if I worked hard enough, I would be able to achieve the role of coxswain as had several of my family beforehand."

Technology has changed much about the way lifeboat crews respond. Pagers have replaced maroon flares and tractors mean the boat can be taken to water mechanically, rather than being pulled on ropes by dozens of volunteers.

RNLI

RNLIThe slipway in St Ives has been moved to a position directly in front of the station and the boats are unrecognisable from the old open-topped, wooden craft.

Mr Cocking explained: "Back then they had a boat, a motor and a compass - yes, the boat could self-right - but that's it.

"Now we have the latest technology, safety, training and equipment to ensure that when we launch to a rescue we are as protected and safe as can be.

"Back then it was a boat launched by the hands of volunteers into the sea and open to the elements."