Cambridge University study reveals man's trade in Aboriginal remains

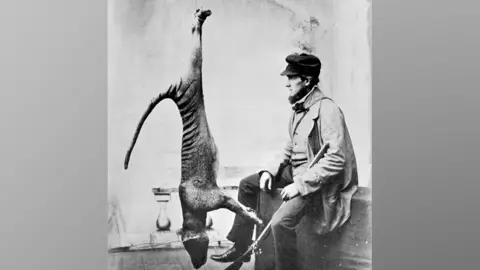

Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State Lib

Allport Library and Museum of Fine Arts, State LibA Victorian solicitor built his scientific reputation by trading the remains of Aboriginal people and Tasmanian tigers, a study has revealed.

Morton Allport, from Hobart, Tasmania, used the remains to gain "recognition from scientific societies".

Jack Ashby, from Cambridge University, has identified him as the "principal exporter of the bodily remains of Tasmanian Aboriginal people to Europe".

The last person of solely Indigenous Tasmanian descent died in 1905.

The last Tasmanian tiger or thylacine became extinct in the 1930s.

Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery

Tasmanian Museum and Art GalleryIn 1830, colonisers established bounties encouraging violence against both Tasmania's first peoples and thylacines.

They were both seen as "a hindrance to colonial development - and the response was institutionalised violence with the intended goal of eradicating both" from the Australian island state, said Mr Ashby.

The assistant director of the university's Museum of Zoology examined transcriptions of Allport's letters, mostly held at the State Library of Tasmania, to correspondents in Australia and Europe.

He discovered Allport "identified himself as the principal exporter of the bodily remains of Tasmanian Aboriginal people to Europe".

None were sent to the University of Cambridge, but it does have one of the world's best-preserved collections of skins of the thylacine.

University of Cambridge

University of CambridgeIn all, Allport shipped five Tasmanian Aboriginal skeletons to Europe and made it clear in his letters that he directed grave-robbing.

This included acquiring the remains of William Lanne - believed by colonists to be the last Tasmanian man when he died in 1869.

The events surrounding Lanne's death have caused debate in Tasmania. It was recently agreed that a statue of a Victorian politician involved in stealing his skull would be removed.

Mr Ashby said Allport's role had been little explored until now.

"Allport's letters show he invested heavily in developing his scientific reputation - particularly in gaining recognition from scientific societies - by supplying human and animal remains from Tasmania in a quid pro quo arrangement, rather than through his own scientific endeavours," said Mr Ashby.

University of Cambridge

University of CambridgeThere were an estimated 4,000 Indigenous Tasmanians and about 5,000 thylacines at the time of European settlement in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Mr Ashby said: "Although Allport did not send any human remains to Cambridge, I can no longer look at these thylacine skins without thinking of the human story they relate to.

"It shows how natural history specimens aren't just scientific data - they also reflect important moments in human history, much of which was tragically violent."

The human remains sent to the UK are no longer held in British collections - they were either destroyed by bombing during World War Two or have been repatriated to Tasmania.

A skeleton sent to Brussels in 1873 is still believed to be held by the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences, but researchers there are calling for legal changes to facilitate the repatriation.

Follow East of England news on Facebook, Instagram and X. Got a story? Email [email protected] or WhatsApp 0800 169 1830