Children of the 90s: Bristol's 'gift to medicine' turns 30

CO90s

CO90sIn the early 1990s, posters began to appear in GP surgeries, libraries and pharmacies across Bristol asking pregnant women to volunteer for a new study. More than 14,500 answered the call. Thirty years later, the Children of the 90s study is the most detailed project of its kind anywhere in the world. Crucially, the huge amount of genetic data it possesses has also come to the fore as the medical world tries to understand, and combat, Covid-19.

In a nondescript building just off Whiteladies Road in Bristol, a treasure trove of medical data is contained in several enormous freezers.

More than 1.5 million biological samples, including blood, placenta, urine, hair, nails and teeth, along with thousands of questionnaires, are overseen by a team headed by Professor Nic Timpson.

The combination of those samples and information collected over the past three decades has generated hundreds of pieces of new medical knowledge, from links between medication taken while pregnant and your child's wellbeing, to the way social media can lead to self-harm and suicide and how a mother's personality can affect her children's mental health.

CO90s

CO90sOne of the study's earliest contributions was backing up the theory that putting babies on their backs at bedtime reduced the risk of cot death or Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) as it is now more commonly known.

Data harvested as part of Children of the 90s also showed the presence of peanut oil in some lotions sensitised children to allergy.

Now the participants are contributing to experts' understanding of long Covid, sending in blood and other samples to help academics piece together why some people suffer for longer than others.

CO90s

CO90s CO90s

CO90sProf Timpson says the "outstanding" feature of the study is the way it has measured life events among its participants over a 30 year period, making it "unique in the research world today".

"Take pregnancy for example," he said. "We have details of about 15,000 pregnancies that happened in the 1990s. We're now going through the cycle again, but with pregnancies from 2020.

"So we can look at things like perinatal mental health, and the way aspects of pregnancy and the experience of being a mum are changing - particularly in areas such as mental health.

"In this case, evidence suggests that something is changing and it could be that the circumstances surrounding mums are particularly difficult in terms of returning to work or social media, and so on."

Sam Frost

Sam FrostCurrently about 27,800 people contribute to Children of the 90s - 11,900 mothers from the original cohort, 3,400 fathers, 11,300 children of those original parents and 1,200 grandchildren.

Sometimes, said Prof Timpson, the team makes discoveries purely by chance, such as in the area of how wounds heal.

"Cuts and lacerations are important, as is scarring, but things like fibrosis and internal wounding are related and important for disease and understanding biological pathways that can be involved in cancer development," he said.

"But this is a very difficult thing to study - you can't just go around intentionally wounding thousands of people."

They then realised that through their data on BCG injections - which left a small laceration - they could bring together factors like wound size and genetics to increase their understanding of the biology of this human trait.

"That wasn't necessarily by design, but came out of the breadth of the data in the study," he said.

CO90s

CO90sThe study is curated by University of Bristol academics, and if it were a person it would speak with a Bristol accent.

Later this year it will launch its biggest-ever collection of health data based on three generations of Bristol families.

More than three quarters of the original children are still based in the city, and Prof Timpson acknowledges his team - and the global scientific community - owe them enormous gratitude.

"Without the dedication of the participants, we would literally have no study," he said.

"The fact that so many of the original mothers are still regularly appearing in the study is mind-blowing really."

Humble beginnings

Sam Frost

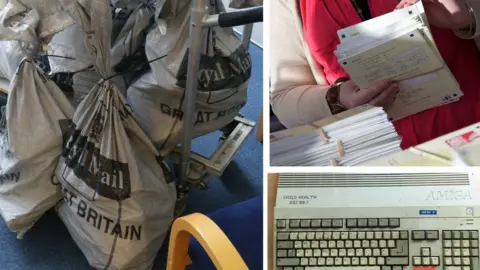

Sam FrostProfessor Jean Golding OBE, now 81, was the person who began the study which started, in her words, "with a few pennies and a prayer".

Staff worked on month-to-month contracts, and it took years before large research bodies appreciated the importance of what Prof Golding and her team were doing and began to fund it.

"In my wildest dreams I thought we might follow the children until they were aged seven," she said.

"The amount of information we've got now is world-beating, nobody's got anything like it. And as a result all sorts of different scientists can answer questions that can't be answered any other way."

'We got to miss school'

Josie Ball

Josie BallJosie Ball's mother was part of the original study, meaning Josie and her twin sister Zara contributed while they were still in the womb.

Josie has been taking part in the study her whole life, and now her children are also contributing, as are Zara's. Most recently Josie has been contributing to Covid-19 studies at the Children of the 90s clinic exploring the immune response to the virus.

"I remember it was something quite fun to do when I was young, because we got to miss school and we always got a toy at the end of the day," she said.

Now she fills out regular questionnaires for each of her four children, as well as passing on updates on her own health, while also learning from the data she helps compile.

"Two of my children are autistic, and I know they are looking into whether that has a genetic link, so I'm interested to see what results they come up with," she said.

"Because we've been involved in the study for so long we just think of it as the norm, not as anything special. But when you read articles and see it on the news you think 'wow, we could really be making a difference'."

Josie Ball

Josie Ball Zara Rose

Zara RoseFollow BBC West on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: [email protected]