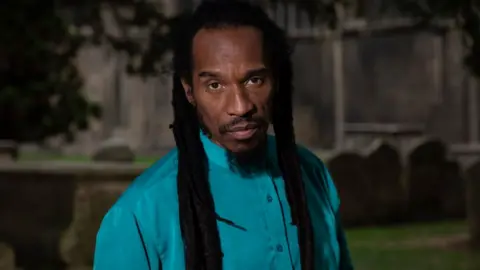

Benjamin Zephaniah: The James Brown of dub poetry

BBC

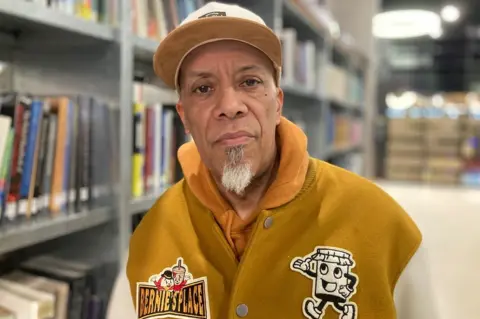

BBCA man who had a "massive history" with writer and poet Benjamin Zephaniah, as a long-time friend, has spoken of a "humble man" who had huge integrity.

Birmingham City University academic Dr Martin Glynn performed with Zephaniah, who has died aged 65, in the 1980s and said they were sounding boards for each other until a few weeks ago.

The poet talked "about issues that related to black people" and "made them universal", Dr Glynn said.

But family were central to who he was.

The writer died on Thursday after being diagnosed with a brain tumour eight weeks ago, a statement on his Instagram said.

Zephaniah was born and raised in Handsworth, Birmingham, the son of a Barbadian postman and a Jamaican nurse. He was dyslexic and left school aged 13, unable to read or write.

His work is often described as dub poetry, staged to music which typically draws on the rhythms of reggae.

Dr Glynn, who is also a poet and author, said: "He was the James Brown of dub poetry, the godfather.

"Linton Kwesi Johnson spoke to the political classes, but Benjamin was a humanist, he made poetry popular and loved music. He had his own studio.

"He did what John Cooper Clarke did with poetry and that was bringing it into the mainstream."

PA Media

PA MediaDescribing Zephaniah as "very humble", the academic worked with him for four decades and stated he "was there when he turned down his OBE".

Dr Glynn said: "The vitriolic response to when he turned it down was massive. So, for me my memory of Benjamin is yeah as a poet, as an artist, but he had massive integrity.

"I just hope anybody watching this [interview] understands that integrity trumps status, profile, ego and personality."

Zephaniah "stood for people with a disability" and he was "very passionate" about the environment.

"He was just passionate about the average person and he also wanted people to share the love of words in the way that he did, because he didn't come up the easiest route," Dr Glynn said.

Zephaniah was also patron of Acorns Children's Hospice in Walsall, and paying tribute on Friday, it talked of him bringing joy to families during his visits.

It said he "understood deeply" its ethos and that faces would often "light up in his presence" and during his performances.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Glynn said Zephaniah was "never an establishment person", but "got into spaces" where he felt he could be heard.

"He'd do [the BBC's] Question Time... He did it because he wanted to show that people like Benjamin can be on Question Time," he said.

The academic stated he himself wanted to be interviewed at Birmingham library on Thursday, because "when we started, libraries were the only spaces to give black poets a voice".

He said: "I remember seeing [Benjamin] on Channel 4 just before I started [doing poetry] and so I wrote to the Edinburgh Fringe to say 'hi' and he came back to me.

"He got in touch with a note to say we would perform together in Birmingham and he gave me my first gig."

If Zephaniah was performing somewhere, he would always phone poets in that area and offer to "pick you up in the car", Dr Glynn remembered.

"I was performing with him in Bedford. He turns up, he didn't have a bag - nothing. I remember saying 'where's your stuff?'

"And he replied 'oh I don't write anything down'."

Zephaniah "went on and became this huge person, but his family were central to who Benjamin was".

The academic stated: "Everyone I've spoken to today has cried. There's this guy, a tough guy, when he came on the phone, he couldn't speak. He broke down and cried.

"Benjamin was super fit. He was a vegan and I suppose really when we see our icons, we think they're going to live forever... That's the status that Benjamin had."

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: [email protected]