The Birmingham child who paved the way for the heel prick test

Birmingham Children's Hospital

Birmingham Children's HospitalNewborn heel prick tests are routinely used to screen babies for rare health conditions, but generations of infants might have gone undiagnosed had it not been for a trail-blazing medical team and one mother's refusal to give up. Retired consultant scientist and biochemist Prof Anne Green has spoken to the BBC about the story of pioneering patient Sheila Jones and her mother Mary.

In October 1949, Mary Jones brought newborn daughter Sheila home to live with her two older brothers at Matlock Road in Tyseley, Birmingham.

At first the child flourished, but as the months went by, Mary noticed she was not developing as expected.

A doctor referred Sheila to Birmingham's Children's Hospital.

At 17 months, Sheila was seen at the hospital's clinic for children with learning disabilities, run by a Dr John Gerrard.

She could not stand, walk or speak and her mother reported she would lie in her cot groaning, rocking and rolling her head.

Birmingham Children's Hospital

Birmingham Children's HospitalWeeks earlier, German PhD student Dr Horst Bickel had introduced testing for metabolic disorder Phenylketonuria (PKU) for the clinic's patients.

People with PKU cannot break down phenylalanine, an amino acid found in protein foods. If left unmanaged, the build-up causes brain and nerve damage.

Under the direction of biochemist Dr Evelyn Hickmans, the hospital's cutting-edge lab confirmed Sheila had PKU, a condition then considered untreatable.

"There's a lot of serendipity in it," said Prof Green. "You couldn't have had a better team in the era."

Sheila's mother Mary refused to accept her daughter could not be helped.

She would wait for Dr Bickel outside the laboratory: "Making quite clear it was treatment she wanted for her child, not fancy investigations," said the professor, referring to the doctor's notes.

Mary's sons could hardly believe her tenacity, added Prof Green. "They say that she was very quiet - but I think when it comes to your child it's a different matter isn't it? She wanted treatment and she got it."

What is Phenylketonuria (PKU)?

- PKU is a rare metabolic disorder which affects about one in 10,000 babies born in the UK

- People with PKU cannot break down the amino acid phenylalanine, a building block of protein, which gathers in their blood and brain

- It can cause severe and irreversible brain damage if left unmanaged

- Medical intervention now includes a special diet and regular blood tests

- PKU is one of nine conditions babies are screened for by the NHS

Galvanised, doctors Bickel and Hickmans set to work day and night on creating the world's first low-phenylalanine dietary treatment.

"They obtained casein, the protein that's in milk… and using acid were able to break down the proteins into individual amino acids," explained Prof Green. "They treated it with the acid and then passed it through the long glass column full of charcoal."

The resulting liquid protein supplement was "quite disgusting," she said. "The brothers describe it as like tar."

Birmingham Children's Hospital

Birmingham Children's HospitalSheila drank 100ml doses twice daily, alongside fruit, vegetables, flour and water and a small amount of milk.

Within months, she responded, learning to crawl and climb on chairs. Soon, she walked unaided.

"It was an amazing feat," said the professor. "Once they proved Sheila was benefiting, then things took off."

The diet became available to more patients and pharmaceutical companies started to reproduce it.

"[Sheila's] part was huge," said Prof Green. "It showed that making a diet was possible."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut, the girl began to resist her treatment as she approached the age of six. The liquid had been exchanged for a company-manufactured white powder, but it was still "absolutely awful".

Despite making improvements, Sheila's progress had stalled and it was unclear to medics how long she should continue.

So, the treatment was stopped in December 1955. Sheila's last recorded child assessment the following April judged her to be functioning at the mental age of a child of 18 months.

"If she hadn't had the diet, I suspect she would have had even more issues. But it didn't benefit her so much long-term that she could live a normal life," said Prof Green.

Doctors Gerrard, Hickmans and Bickel had all moved on from their roles in Birmingham.

Mary and her children moved to a back-to-back in a deprived part of Aston and the pioneering patient was not followed up.

Sheila Jones became lost to the healthcare system and, for decades, forgotten.

'Rediscovering Sheila'

Birmingham Children's Hospital

Birmingham Children's HospitalOne of Prof Green's first jobs in Birmingham in the late 1960s was to run newborn checks for PKU.

The city had pioneered a nappy screening test in 1959, proving such assessments could be done on a large scale.

Prof Green first noticed the dusty glass column used decades earlier to prepare the first PKU treatment on a shelf in her boss's office at Birmingham Children's Hospital in 1971.

She thought little more of it at the time, but the column was still there when she inherited the office some years later, eventually taking charge of the hospital's pathology labs.

Then, in 1987, a PKU screening drive turned up a patient called Sheila Jones in Chelmsley psychiatric hospital, Marston Green.

"It just clicked in my mind that I knew the [first] patient was called Sheila," said the professor. When a psychiatric team confirmed her identity "it was a eureka moment in the lab".

Prof Green decided to make contact with Sheila's family and begin researching her story in earnest.

Birmingham Children's Hospital

Birmingham Children's HospitalRecords reveal Sheila was formally admitted to Chelmsley in 1959, with Mary continuing to visit her until she died in 1981.

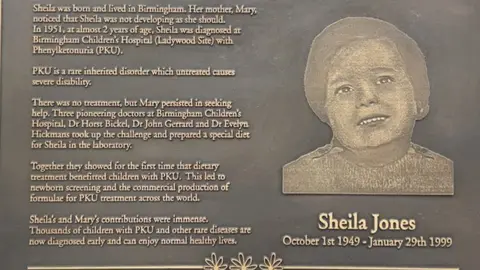

Sheila died aged 49 on 29 January 1999, while living in shared accommodation at Brooklands Hospital, Marston Green.

If born today, she would have been screened and placed on a special diet within a week of birth, said Prof Green.

"Her parents would have been helped - there's a whole team now at Birmingham Children's that supports patients with this condition," she added. "The products are completely different, they're a lot more able to do the diet. There's no comparison."

Prof Green believes the discovery of the low-phenylalanine diet that helped Sheila precipitated the national rollout of screening for PKU in 1969.

"I think without that first case, it wouldn't have taken off quite so quickly," she said. "It did pave the way for newborn screening."

'A mother's insistence'

An award recognising Mary Jones's advocacy was created by the European Society for PKU in 2017.

"It's about what parents, families do for individuals with PKU, the model being Mary Jones," said Prof Green.

In October, Sheila's brother watched as a plaque commemorating his sister and the team that treated her was unveiled at Birmingham Children's Hospital.

"As a family we find it unbelievable... our mother's insistence in finding help for Sheila has led to people all over the world being tested and treated for PKU," he said.

Prof Green, who published their story in Sheila: Unlocking the Treatment for PKU, said: "The [family] hadn't really had any inkling as to what the impact had been - what their mother and their sister had contributed.

"Now I feel the family have got their acknowledgement of what they contributed because it wasn't easy for any of them."

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: newsonline.westmidlands@bbc.co.uk