Ex-gang members speak out on Birmingham gun crime

BBC

BBCAs a spate of shootings and murders - many linked to gangs - adds to Birmingham's surging gun crime tally, former members of the city's notorious crews talk about "street life" and why they want to stop the new generation following their example.

"How bad was I? Bad. I was a terrorist. I'd hear something has happened to someone, put the phone down and go."

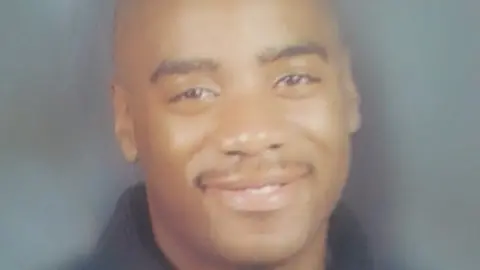

Simeon Moore was in his youth a part of Aston's infamous Johnson Crew, the gang known mainly for its rivalry with the equally disreputable Handsworth Burger Bar Boys in the 90s and early 2000s.

Both groups were involved in murders and tit-for-tat shootings across the city, including the high-profile murders of Charlene Ellis and Letisha Shakespeare at a New Year's party in Aston in 2003.

The teenage friends were killed when Burger Bar members opened fire with a sub-machine gun on party-goers in a botched gang retaliation - a public slaying which marked the city out in the national press as having a gang problem.

More than a decade later and the West Midlands, more specifically Birmingham, has earned itself the title "gun crime capital" of England and Wales.

According to the latest Office of National Statistics figures, the police force's area had more than double the national average of gun crimes between 2015 and 2016, with 19 offences per 100,000 residents.

In the city itself, there was a 14% increase in shootings and of all gun crimes recorded in the region in 2016, 57% were recorded in Birmingham.

Family photo

Family photoMany incidents were linked to the same gangs made up of a new generation of members who watched those who came before them.

Growing up, Moore recalls how the people he saw "doing well" were doing "gangster stuff" and how aged 11, he joined in - robbing, stealing and selling drugs, before progressing onto carrying weapons.

"That's where I got my inspiration from," he says candidly. "I [was] only going to go one way.

"But if anyone who leads that kind of life says they like it, they're lying.

"You're waiting for your door to be kicked off by police and you're always watching you back. People who say it's good, are trying to live up to the image of a gangster with all the money, cars, jewellery."

Now 36 and with six prison stints on his record, he realises how desensitised he became to the "street life" culture - carrying a gun, he remembers, became second nature.

"The first time you have a gun around you, you're probably scared, but keep it on you long enough, it becomes like nothing else, like wearing a watch."

West Midlands Police

West Midlands PoliceGill Foskins knows only too well the harrowing consequences of walking among those who carry guns as a matter of course.

Her 24-year-old son Dimitri, whose nickname was Smiler, was shot at least three times by Dani Watson in the Newtown area of the city in 2008.

Dimitri was not a member of any gang and instead acted as a peacemaker in the community, his mother says. She believes the city's gun problem is rooted in a vicious circle of family members encouraging younger relatives.

"You see the ages of the people dying and you think, 'here we go again' but it comes from higher up - the older ones, in their 50s, bringing the weapons in.

"I'm assuming they have families of their own, but they obviously don't care.

"It's hard. You can be the cousin of somebody and have not done anything and you can be attacked. It's like that. People arm themselves in case they're attacked."

Birmingham has for decades been inextricably linked to guns and gangland crime, according to Dr Mohammed Rahman, a criminology lecturer at Birmingham City University.

"We have a legitimate history of firearms production - Birmingham Small Arms in Small Heath was the sole supplier [of rifles in the UK] during World War Two.

"When it comes to guns being used in the city, [some are] antique firearms.

"They're being used because they are obsolete and often criminals don't want to use so-called dirty weapons, preferring old revolvers that can be used because... the bullets aren't traceable."

In November, firearms dealer Paul Edmunds, was jailed for supplying illegal handguns and homemade ammunition to fit antique weapons to more than 100 crime scenes, including two murders in Birmingham.

The same month, 250 weapons - including rifles, shotguns, revolvers and handguns - were surrendered during a two-week firearms amnesty to West Midlands Police, which has earmarked a further £2m to spend on tackling the problem on top of the millions already spent.

Crucially, a "landmark ruling" banned members of the Burger Bar Boys and Johnson Crew from parts of Birmingham, and there have been no prosecutions for breaching it so far.

And yet, as recently as October, there have been numerous shootings, one in Small Heath, another in Handsworth and a third in Winson Green. In Hockley a month earlier, a man was shot dead.

Though gang-related murders have not reached the heights of 2003 when 27 were recorded, between April 2015 and 2016, West Midlands Police dealt with more than 540 firearms incidents across its patch.

Many were at hotspots in Handsworth and Lozells, Lee Bank, Balsall Heath, Washwood Heath and Bordesley Green - some of the most deprived areas in the country.

Extensive research done by Birmingham Council's Commission on Gangs and Violence reported "people are afraid" of these "spontaneous, chaotic, premeditated" acts of violence.

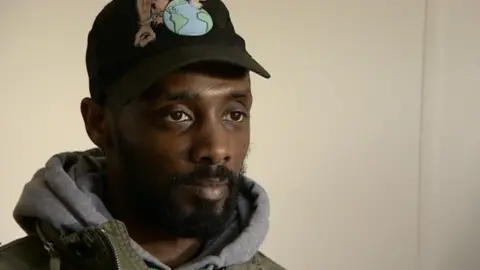

Big Stygs, whose brother Rodrigo Simms is serving a 27-year sentence for acting as a "spotter" for the Burger Boys in the New Year murder, believes the youngsters behind the troubles are copying the actions of their forerunners, and "don't even know what they're fighting for".

"It's out of control," he says.

"They don't see sense, they just think this is the life to live."

But Moore and former Burger Bar member Dylan Duffas are hoping to reach the new generation of gang members through their YouTube channel Dats TV and show them "joining a gang really is.... stupid".

They became friends after becoming involved in the 2013 film One Mile Away, which charted the process of trying to bring peace between the Burger and Johnson gangs.

"After we did the documentary, there was no gun violence in the city for 18 months," says Duffas.

"But it was hard to keep the momentum up and there was a lack of support form the community. And we needed mentoring ourselves because we was fresh from the streets. we were like 'we want to do this we want to do the right thing, but how do we do this?'

"Now, it's a few kids involved and a few kids who have got access to guns and they are out there saying look at me... [they're] not career criminals.

"The culture the Burgers and Johnson Crew created is what the kids are looking to now. Those names are notorious and it up to us to say 'no, that ain't cool'."

For Moore, the glamourised gangster image portrayed in music and film does little to help the problem and mainstream outlets should stop promoting it as a lifestyle, because "the kids listen to it, suck it up and it helps shape their opinion".

He wants to see an end to the city's generational gang cycle.

"It's hard to talk to the youth but I am telling them they've got to stop being a slave to this thing called street life... it's destroying our communities and our families.

"I've lost family to it. I've lost years off my life and a whole heap of friends. To me it's only losses. There's no winning on the streets."