Long Covid: 'I have to choose between walking and talking'

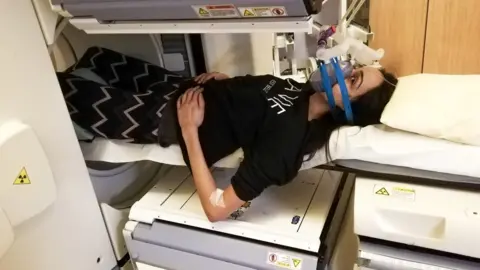

Jasmine Hayer

Jasmine HayerMore than a million people in the UK are suffering from long Covid, with fears the number could rise due to the Omicron variant. Many patients say they only had a mild initial infection but it went on to ruin their health, social lives and finances.

Jasmine Hayer, 32, was living in London and training to be a yoga teacher when she caught coronavirus last March.

It sometimes feels like it was a different person, she says, speaking slowly and carefully from her parent's house in Biggleswade, Bedfordshire.

She moved back there last summer when she realised she couldn't even make her bed without becoming breathless.

"This illness is so baffling and no-one really knows how to treat it. I honestly don't know if I will ever get back to full health but I'll never stop trying," she says.

Jasmine Hayer

Jasmine HayerCurrently on sick pay and previously furloughed, she is desperate to work again.

"My whole life has been pulled out from underneath me like so many others with long Covid. We've had a big identity crisis," she says.

"I need to reinvent myself. I can't even lift my left arm up, let alone be a yoga teacher, which is heartbreaking."

For nine months, doctors said anxiety was the cause of her symptoms, which included a tight chest, heart pain, breathlessness, fatigue and palpitations.

She knew they were wrong and developed her own symptom tracker which helped her work out that her triggers were bending over, walking and talking, with a delayed impact in her lungs.

Her health only began to improve when she started treatment at a clinic for 130 patients with severe long Covid, at the Royal Brompton Hospital, in London.

Jasmine Hayer

Jasmine HayerDoctors found multiple health issues. A gas transfer test showed oxygen levels in her lungs to be 53%, the same as a lung disease patient, and she was diagnosed with post-Covid heart inflammation, which they told her they had not seen before.

They also found small blood clots on her lungs, which only showed up on a specialised scan called a ventilation-perfusion scan.

Since starting blood-thinning medication, the clots have gone but she still has abnormal blood and oxygen flow to her lungs.

"An anti-inflammatory drug called colchicine significantly changed my recovery but unfortunately I relapsed again. Now I can walk slowly for five minutes once a week if I'm lucky but I get chest pain afterwards. I have to choose between using my voice and moving my body. I can't do both in a day.

"Doctors don't know why I have good overall levels of oxygen in my body but it's not getting to my lungs, which could be an issue with my blood vessels, but my scans show they are normal - they've never seen this before."

Jasmine Hayer

Jasmine HayerSince starting a blog about her story, she has been contacted by hundreds of people with long Covid desperate for help.

"Many patients are being dismissed because their GPs and specialists haven't been given enough guidance. They don't know that patients can have micro blood clots but normal scans and blood test results, like me," she says.

Jasmine is closely following an ongoing study in Germany which found microscopic blood clots in long Covid patients, starving their tissues of oxygen. A technique that cleans the blood, removing disease-forming proteins, has helped some patients there.

She is also a patient adviser on the largest long Covid study in the world to date, which aims to improve diagnosis and treatment of the illness.

Jasmine Hayer

Jasmine HayerProf Amitava Banerjee, from University College London, is leading the two-year STIMULATE-ICP study which will recruit 4,500 patients from six long Covid clinics.

Existing drugs will be trialled to work out their effectiveness, including anti-histamines, such as the hay fever treatment loratadine. Anti-clotting drugs like rivaroxaban and the anti-inflammatory drug colchicine will also be tested.

Cardiologist Prof Banerjee is concerned that the current number of infections will result in more people suffering with long Covid.

Many patients developed it after a mild infection, he says, so he is not reassured that the Omicron variant may produce less severe initial illness.

"We know that people who were not hospitalised with acute Covid have gone on and been more impaired and we should be concerned about that," he says.

Vaccines are undeniably helping prevent death and severe illness but scientists do not know yet if they protect against long Covid, he says.

Many young people with long Covid have not been able to return to work, he adds, and this has had a major impact on their health, wellbeing and the economy.

He believes the best way to prevent it is to "avoid getting infected in the first place and keep the infection rate down", which will not be achieved with a vaccine-only approach, he says.

"I would love to see more consideration, debate and acknowledgement of long Covid from our policy-makers," he says. "If you only measure deaths you miss out the impact on peoples' lives. We should know better than this."

The Department of Health and Social Care has been asked for a response to Prof Banerjee's comments.

What is long Covid?

- Long Covid covers a broad range of symptoms including fatigue, coughs, headaches and muscle pain

- Most people who get coronavirus feel better in a few days or weeks but symptoms can last longer for some, even after a mild infection

- An estimated 1.2 million people reported having long Covid in the UK in the four weeks to October 31

- Women and those aged 35-49 are most likely to report long-term symptoms

- Some 40,000 healthcare workers in the UK are estimated to have long Covid

- NHS England has invested £134m to support those with long Covid and opened 90 dedicated clinics across England

Source: Office for National Statistics/NHS

For Emily Miller, long Covid continues to be a terrifying and lonely experience, without the input of supportive medical specialists.

The 21-year-old had just returned to studying for a music business degree in Brighton last October when she fell ill with coronavirus.

Emily Miller

Emily MillerGrowing up in Oxford, she walked everywhere and enjoyed trips to the theatre. Now she only leaves the house for medical appointments and lessons.

"By the end of my classes, I feel drunk and can't remember what has been said.

"I don't see my friends or have a social life. My life has completely changed and so has my career trajectory."

After an initial mild infection, she started to experience migraines, tinnitus, numbness, breathlessness, dizziness, nose bleeds, chest pain and nausea.

A blood test showed she had a low white blood cell count and she was referred to a long Covid clinic, which helped with fatigue management. She was then referred to a neurologist.

Meanwhile, Emily said a GP told her the symptoms were down to anxiety and she should "go home and sort myself out".

Emily is still on pain medication and suffers from fatigue, muscle spasms and gastrointestinal issues. Her GP recently suggested it was anxiety-related irritable bowel syndrome.

"I would love to have some more tests and investigations to see what is causing this but I keep hitting a brick wall," she says.

Apart from her health, her biggest concerns are financial and she worries about paying her rent every month.

"I applied for a disabled students' allowance but they do not recognise long Covid as a disability. I really hope one day it will be counted," she says.

Her job prospects when she graduates next year are bleak, she feels, and her dream of working for a record label is on hold.

Emily Miller

Emily MillerShe decided to set up a fundraising page to help support herself and try to ultimately find a cure by paying for experimental treatments like oxygen therapy.

"I hate asking other people to support me but I felt like I was running out of options," she says.

It's a similar situation for Antony Loveless, who recently had to ask his mother to lend him £1,000 to pay his mortgage.

The 54-year-old, who lives in Southend, caught Covid in January while he was at work as a lead investigator at London Gateway port.

His partner Claire Hooper, 52, who was working as a nurse, caught it too and also suffers from long Covid.

They have spent most of this year in bed with crippling pain and fatigue, having both been made redundant from their jobs.

Antony Loveless

Antony LovelessAntony has lost four stone, walks with a stick and drives a car with a disabled badge. He has been diagnosed with a loss of white blood cells and an autonomic disorder called postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, which affects his ability to regulate blood pressure. Claire has lost six stone and now has diabetes and hypertension.

Both have been discharged from a long Covid clinic, having been told they were too ill to start rehabilitation.

They burned through £10,000 of savings just paying their mortgage and bills, before they recently qualified for benefits.

"We had an enjoyable middle-class lifestyle," Antony says. "We went from earning around £4,500 a month to living on the bare minimum."

The former war photographer and author has to set reminders on his phone to go to the kitchen to eat but then can't remember why he is in there.

Antony Loveless

Antony Loveless"I hadn't smoked in 37 years and forgot I didn't smoke and bought a packet of cigarettes the other day," he says.

He feels frustrated that statistics are collected on people with Covid who live and die but "not the people in the middle".

"The government never talks about long Covid, you either die or recover, but what about us?"

He says things got so bad a few months ago that he and Claire considered ending their lives.

"We got to a point where we couldn't go on with the pain and no quality of life. We had run out of money and options and were lying in bed, not even able to follow a plot on TV."

Antony says they feel like they have been left floating in the wind.

"We will just keep living and hoping we will get better, that's all we can do," he says.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. If you have a story suggestion email [email protected]