Holocaust Memorial Day: Kindertransport refugees who made Britain home

Holocaust Educational Trust

Holocaust Educational TrustThe voice of Adolf Hitler is forever "locked" into the memory of 92-year-old former Kindertransport refugee John Fieldsend BEM, who arrived in England in 1939.

Loudspeakers in the streets of Dresden, where his family lived in Germany, made Hitler's booming rants about Jews inescapable - even from home.

At the age of five, John's life began to change. Friends he had known for years suddenly turned against him, becoming violent and calling his family "dirty Jews".

After cutting his head on a radiator at home, John was taken to the doctor who said he needed stitches - but was told: "I don't stitch Jews."

His parents knew they needed to leave, so drove to John's grandparents' house in Czechoslovakia. Things were secure again for the family until Hitler invaded in March 1939, when John's life was turned upside down again.

This Holocaust Memorial Day, Kindertransport refugees who made England their home have shared their stories with the BBC.

The Kindertransport (German for 'children's transport') was a series of rescue efforts between 1938 and 1940 that brought about 10,000 mostly Jewish refugee children to Great Britain from Nazi Germany.

John was one of the 669 children who escaped Czechoslovakia without their parents through the trains arranged by British stockbroker Nicholas Winton, a story that was recently brought to the big screen.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt seven years old, John recalls the "bewilderment" he felt when he was taken to the local train station with his brother Arthur and watched their parents wave goodbye.

"I think the crunch point came when my mother took her wrist watch off, passed it through the window to me and said, 'This is for you to remember us by'," he said.

On arrival in England, John and his brother were eventually separated and lived with different foster families in Sheffield.

"My first memory was actually seeing an open coal fire," he said. "On the continent we'd only ever had closed combustion stoves - I thought the house was on fire!"

He describes his foster parents as "just lovely...very caring" people, and lived with them until he got married in 1961.

Now a retired Anglican vicar, father of three and grandfather of seven, John lives in Oxford and works with the Holocaust Educational Trust to share his testimony.

John Fieldsend

John FieldsendIn 1942, he stopped hearing from his parents in Czechoslovakia.

Soon after the end of World War Two, the Red Cross delivered a parcel to John containing photo albums and a farewell letter written by his parents before their internment in a concentration camp in Nazi Germany occupied Poland.

It's a letter John still holds to this day, the words retain the searing poignancy of one family's tragedy.

John Fieldsend BEM

John Fieldsend BEMDear Boys,

From Mother

When you receive this letter, the war will be over, because our friendly messenger won't be able to send it earlier. We want to say farewell to you, who were our dearest possession in the world, and only for a short time were we able to keep you.

Fate has not left us for months now. In January 1942, the Weilers were taken; we still don't know where to and whether they are still alive. In June, Grandmother Betty. In September, Aunt Marion, Uncle Will and Paul. In October, your Steiner grandparents. In November, your 90-year-old great-grandmother and the Bermans. In December, it will be our turn.

The time has therefore come for us to turn to you again, and to ask you to become good men, and think of the years we were happy together. We are going into the unknown; not a word is to be heard from those already taken.

Thank those who have kept you from a similar fate. You took a piece of your poor parents' hearts with you, when we decided to give you away. Give our thanks and gratitude to all who are good to you.

From Father

Your dear mother has told you about the hard fate of all our loved ones. We too will not be spared and will go bravely into the unknown, with the hope that we shall yet see you again when God wills. Don't forget us, and be good.

I too thank all the good people who have accepted you so nobly.

Signed,

Curt & Trude Feige, 1943

'Not just a victim community'

For John, the Holocaust must continue to be remembered, even amongst the many terrible things happening in the world.

"One thing that we, as a Jewish community, must be aware of, we mustn't portray ourselves as a poor victim community," he added.

"We've got much more to contribute in a positive way than that. We are not just a victim community."

Karen Pollock CBE, chief executive of the Holocaust Educational Trust, said the reported rise in antisemitism meant "it is more important than ever to remember the six million Jewish victims and remind ourselves that anti-Jewish racism did not begin nor end with the Holocaust".

Michael Newman, CEO of the Association of Jewish Refugees, the national organisation representing and supporting Holocaust survivors, said they were "acutely sensitised to the fragility of freedom", the theme for this year's Holocaust Memorial Day.

"Today it is vital, that as a nation, we collectively remember the victims of the Holocaust," he said.

"Both to honour those whose lives were ripped apart by antisemitism and to ensure that the experiences of the survivors and refugees, and their families, are never forgotten."

But in 2024, does the UK feel as welcome to refugees as it did when John arrived?

"It's difficult one," he said. "I have to say at the moment, I don't think it is.

"In 1939, Britain was a welcoming place, but it took the hard work of people like Nicholas Winton."

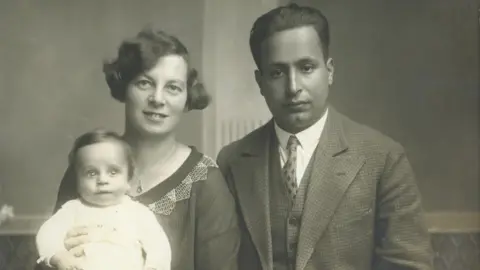

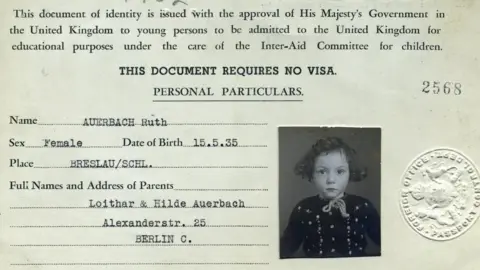

Ruth Schwiening_AJR

Ruth Schwiening_AJRRuth Schwiening, 88, remembers nothing of the Kindertransport.

In 1939, at the age of three, she travelled from an orphanage in Berlin to London.

Meanwhile, her father was imprisoned in Dachau Concentration Camp in Germany, and her mother was left to find a way out of the country for the rest of the family.

"I knew quite a few friends who did remember, and it really, I think, almost destroyed their lives," she said.

"When you get older, you think back to the past, and you try to recollect what has happened, and you're almost eaten by the past rather than the present."

A Jewish organisation had been approaching people whose husbands were in concentration camps to offer the Kindertransport route.

They got in touch with Ruth's mother Hilde, but said they could only take one child.

Ruth says they told her mother: "We can take the girl because girls are easier to be fostered than boys."

She said: "I often ask the question when I'm giving talks: What would you have done? Knowing, perhaps, that you will never see the girl again?"

Ruth Schwiening_AJR

Ruth Schwiening_AJRRuth's foster parents were Mr and Mrs Hart, a middle-class Jewish family in London who had one daughter, Geraldine.

Ruth remembers being happy with her foster parents, and having the feeling of security "probably [for] the first time".

But one day in March 1940, to everyone's amazement, Ruth's mother Hilde appeared at the door.

Her foster parents had been told that her mother and father were in a concentration camp and very unlikely to survive.

"Little Ruth, give me a kiss", Hilde said to her daughter.

But Ruth had forgotten her mother. "I apparently looked at her and said, 'My mummy says I must not kiss strangers'."

All of Ruth's clothes and toys were parcelled up in a big box, and she reunited with her whole family who had settled in Nuneaton, Warwickshire.

Ruth Schwiening_AJR

Ruth Schwiening_AJRIn 1940, the horrors of World War Two were their taking their toll on Hilde.

In the summer and autumn, Britain fought a major air campaign against Germany called the Battle of Britain, to prevent the Nazis' planned invasion.

Ruth's father Lothar had been taken away to an internment camp on the Isle of Man for "enemy aliens", and Hilde feared a successful invasion could spell a death sentence for her family.

Hilde told Ruth and her two brothers: "If the Germans come and fetch us, or try to, there's poison upstairs. I will take the poison, and I'll give it to you as well."

The most important lesson future generations should take from Holocaust survivors, Ruth says, is to "not to judge people by their religion, by their colour, by their race. To recognise [their] prejudices".

"Soon as we recognise a prejudice, we can then learn and try to overcome that prejudice, make us more sympathetic and understanding," she said.

Ruth too believes the warm welcome she received as a refugee wouldn't be as warm today.

"What are we doing thinking of sending people to Rwanda? What are we doing thinking of putting people isolated on cruisers? Which are no more than prisons really," she said, referring to the UK's plan to send asylum seekers to Rwanda and the housing of migrants on a barge.

"I can't understand. We could, as a country, do a lot more."