Abuse support fight 'like being controlled again', say CSE victims

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor more than 10 years, victims of modern slavery and sex trafficking in the UK have been able to apply for government support to help them survive their ordeals. But some women say the system is so complex to navigate it has left them feeling "like being controlled again".

The BBC spoke to two survivors of child sexual exploitation about their long struggle for support.

Jane*, now in her 40s, was 16 and arriving for her first day at sixth form college when she met the man who would force her into having sex with dozens of strangers for money.

After a difficult couple of years at secondary school, she hoped college would be the answer to continuing her education.

The man, in his early 20s, approached her as she turned up for her entrance exam.

"He started chatting me up and he became what I thought was my boyfriend, but he wasn't," she said.

Within weeks of their "relationship" starting, he convinced her to have sex with other men, going on to take her to locations in Birmingham, the West Midlands and London to carry out his orders.

"All his friends - I say friends but some would regard them as gang members - all had what I saw as girlfriends who were all basically on the streets being sold," said Jane.

"It was very normalised because everyone in his social circle was doing the same thing."

She became ostracised from her mum as he took more control of her life.

"I had no friends, no family, no nothing to tell me this was wrong," she said.

What followed was a five-year nightmare that saw her forced to have sex with men across the country and beaten if she tried to escape.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven though she was repeatedly arrested and charged with prostitution under the age of 18 - she has about 40 convictions - police did not recognise she was a victim herself. The offence has subsequently been decriminalised under a 2015 amendment to the Street Offences Act 1959.

Shortly before her 21st birthday, she managed to flee after being left alone in a flat.

She managed to piece a life together. It was not until she was an adult she realised she had been a victim of child sexual exploitation, having seen the widespread media reports about grooming in towns such as Telford and Rochdale.

She reported her case to police in 2018, but no charges were ever brought against those she named as her abusers.

Jane also made contact with the National Referral Mechanism (NRM). It identifies and refers potential victims of modern slavery to ensure they receive appropriate support and the woman said she felt it was a chance to "rebuild my life".

Three years on, she is still waiting.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWithin a year, the NRM concluded Jane had been a victim. This decision should have paved the way for access to legal support with a compensation claim, as well as entitlement to subsistence payments, a £65 weekly payment made by the government to help with living costs.

But she has not received a penny and believes she is owed more than £6,000 in backdated money.

Her criminal convictions have made it difficult to gain regular employment, so the financial help is vital.

"It's been really bad, I've had to choose between putting petrol in my car, buying food, clothes, general shopping, it's been a real struggle."

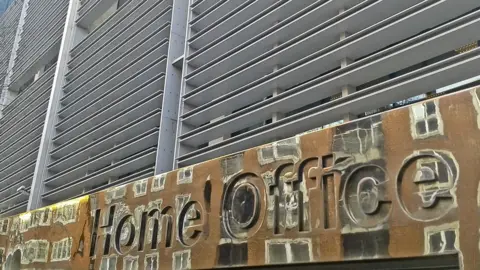

The National Referral Mechanism

The National Referral Mechanism (NRM) is a Home Office framework for identifying and referring potential victims of modern slavery and ensuring they receive the appropriate support.

A person who is suspected to be a victim is referred to the NRM from a first responder agency, which can be police forces, immigration authorities, the National Crime Agency, local authorities or charities such as the Salvation Army, NSPCC or Barnardo's.

Once a referral is made, it is assessed and someone who is believed to have been a victim of trafficking or modern slavery is first given a reasonable grounds decision and can access support before being given a conclusive grounds decision, where it is accepted they were a victim.

A year ago, Jane applied for compensation through the government's Criminal Injuries Compensation Authority (CICA), which deals with claims from people who have been physically or mentally injured as a victim of a violent crime.

But her claim was rejected and when she asked to see the documents explaining why she had been turned down, she said, she only received redacted pages - all details had been completely blacked out.

Other

Other"I opened it and looked in and I was in shock. I looked at my support worker and she didn't know whether to laugh or cry or shake her head," she said.

The organisation said the documents from the Police National Computer had been blacked-out when they had received them.

"It is just horrible. It is like being controlled again," Jane said.

"You are told you have these opportunities… but you have to bang on the door to be able to open it."

Within the past few weeks she has finally been offered some compensation and is discussing whether to accept it with her solicitors.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnother former victim, Emily*, who lives in Wales, was initially exploited through county lines aged 11 before becoming a victim of sexual exploitation between the ages of 14 and 20.

"I was trafficked for hiding drugs to start with, that started when I was 11, then when it was for sex... you'd go to places and get raped," she said.

Now in her 30s, it wasn't until 2019 that she began to realise she was a victim when she began having "flashbacks" of some of the terrible abuse she had endured.

She was referred to the NRM but did not receive positive conclusive grounds until about 18 months later.

Emily then faced a delay of four months in being able to access support, as a suitable provider organisation was not available.

She has a support worker but has not been able to meet her face-to-face as she is based in another part of the country.

Emily had a nine-month wait for subsistence payments then was told they take her above the threshold of eligibility for legal aid, which has meant she has struggled to pursue her case.

'You can't heal'

"It is draining. I feel like I am constantly doing legal aid, constantly trying to get justice, but I know I am not going to get it," she said.

"People who can't afford it do go back into exploitation, you feel stuck.

"You don't get closure until you get justice, you can't heal."

She has also had an initial application for compensation through CICA rejected because it was claimed she failed to cooperate with police.

Emily reported her abuse to police in 2019, she said, but was told they would not investigate as it was "historic" offences, and she was given a form to "sign off" the case.

She felt officers "weren't listening at all, they didn't know what I was telling them... I lost confidence in them completely".

The police were also the "first responder" body who should first have referred her for support through the NRM, she said, but delayed it for three months.

From 1 November 2015, specified public authorities are required to notify the Home Office about any potential victims of modern slavery they encounter in England and Wales.

Both women are concerned about identification and do not want to reveal the police forces involved.

Solicitor Silvia Nicolaou Garcia, who has represented Emily for Simpson Millar, said it had been a "struggle".

"Having to tell her story multiple times is retraumatising and retriggering and in our view having a positive trafficking decision should be enough for survivors of trafficking to access compensation."

Kate Roberts, Anti-Slavery International's UK & Europe Manager, said, in its experience, people "fall between gaps" in support through the NRM "all the time".

"The support system really does leave a lot to be desired and the way you can make good policy work in practice is by having people with lived experience, having it centred around them and have them explain the pitfalls," she said.

"With the survivors I do speak with... they talk about the system compounding trauma rather than enabling them to move on," she added.

Jamila Duncan-Bosu, a solicitor with the Anti Trafficking and Labour Exploitation Unit, who works with trafficking victims to get compensation, said she had had clients die while waiting for their cases to conclude.

Part of the issue she said, is that claims could not be funded through legal aid, but she also believes there should be improved internal guidance for those making decisions on granting compensation specifically related to trafficking and modern slavery cases.

Studies by her organisation found the majority of applicants were waiting two to three years for CICA to determine their applications and award compensation.

"Applications to CICA are generally made by survivors who are unable to identify their trafficker, where the trafficker has no significant assets, or where the survivor is unable to face their trafficker in court," she said.

"Compensation is vital to helping survivors escape the poverty that places them at much greater risk of further harm and re-trafficking.

"The Criminal Injuries Compensation Scheme as it currently operates is failing survivors by regularly denying them the compensation that they are entitled to."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA spokesperson from the Ministry of Justice, which operates the CICA scheme, said it could not comment on individual cases but added: "Trafficking is a terrible crime and we know reporting abuse can be extremely hard, which is why we work with experts to ensure staff know how to support victims of trafficking and identify issues that can affect their applications."

The Home Office said it was continuing to implement reforms to the NRM "aimed at improving the speed and quality of decision making, and offering the best possible support for victims".

A spokesman added: "The government is committed to tackling the heinous crime of modern slavery, enabling victims to rebuild their lives and helping them move on from their abuse."

- If you have been affected by any of the issues in this article, you can find services that can help on BBC Action Line.

Follow BBC West Midlands on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. Send your story ideas to: [email protected]