On the trail of a ruthless slavery gang

West Midlands Police

West Midlands PoliceEarlier this year, eight people were jailed for their part in the biggest slavery network ever discovered in Britain. BBC Panorama went behind the scenes as police and lawyers worked tirelessly with dozens of victims to expose the gang.

"I understand you've been talking to one of my witnesses." The detective on the other end of the line, Michelle Ohren, does not sound happy. "I did not know he was one of your witnesses," I reply: "Anyway. Witness to what?"

There is a sigh at the other end of the line. "Mariusz Rykaczewski is a witness in a modern slavery case we have been investigating for the past two years." Det Sgt Ohren's words seize my attention. With the help of the Salvation Army I have been interviewing former slaves for a possible Panorama on modern slavery.

"Look, I'm happy to help," I say, probing, "can you tell me more?" The answer is a firm "no". But Det Sgt Ohren does agree to put me in touch with her boss, Det Ch Insp Nick Dale of West Midlands Police.

The door to the UK's biggest ever modern-day slavery case has cracked open.

I'd met Mariusz at a Salvation Army base in a northern city.

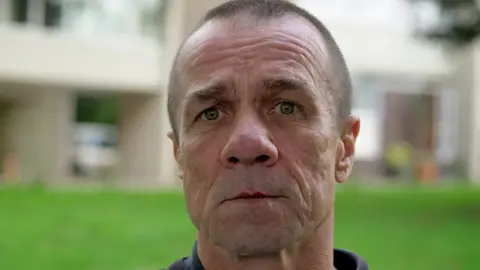

He'd been hiding out in one of the charity's network of safe houses. He told me he'd been a solider in the French Foreign Legion. He looked the part with a battered face and a buzz cut. The story he came out with was at turns highly unlikely and grim.

He was down on his luck in northern Poland when a couple of "Gypsies" made him an offer he couldn't refuse: free travel to the UK, free accommodation and a job. He knew there had to be a catch. "I think at first it's a joke but the day after they call me: 'When am I ready to go?'"

Desperate, he decided to take a gamble. "I take one bag. I meet in this bus station and they give me ticket and I go."

The life that awaited him in the UK was very different to the idyll he had been promised.

'They beat me'

He was housed in a freezing terrace with 12 other men. They were all the same: older guys in their 40s and 50s, many of them alcoholic or homeless, all down on their luck. All were now slaves in a foreign country.

Mariusz slept on the floor and the food he was given was stale. What's more, he was told he'd have to repay the cost of the bus ticket, the out-of-date food and the squalid accommodation.

He tried to escape - and discovered the price of disobedience. "The criminals... they beat me in my ribs and I have black eyes. "Sometimes I sleep with big knife because I'm afraid they come back again."

Isobel McFarlane of the Salvation Army, who introduced me to Mariusz, says his background in the French Foreign Legion may have made things worse for him. "What happened to Mariusz is extremely typical where one individual might be singled out and actually physically assaulted as an example to the other guys."

Mariusz's captors took him along to a local bank to open an account. He was forced to give a fake address under the slavers' control. He never saw the card or withdrew any money from the account.

Only after he'd escaped did he learn the account had been used to run up more than £6,000 in debt. The most he was ever paid for a 60-hour week picking leeks was £75. That's £1.25 an hour.

West Midlands Police

West Midlands PoliceEventually, Mariusz found a number for the Salvation Army slavery helpline.

A woman there told him where the nearest police station was and - crucially - that he'd be looked after when he got there. Within hours of escaping he was on his way to a Salvation Army safe house far from Birmingham and his captors. "They were very kind to me," said Mariusz.

As we parted he told me proudly that he was now training to be a security guard. It seemed as though his life was getting back on track.

Not long after this I find myself in Det Ch Insp Dale's sparse office at Bournville police station in Birmingham. The force currently has multiple unsolved murders. And yet sitting opposite me is an officer firmly fixed on modern-day slavery.

"Mariusz is one of dozens of witnesses," says Det Ch Insp Dale. "I think, in total, there were 300 victims. There's never been a case like it."

I ask the detective if our company, Longtail Films, can follow him and his officers for Panorama. I expect to have to persuade him, have my arguments ready. A life of police work does not make people trusting. His reply surprises me.

"Yes. I believe in being open. The public need to understand the scale of the problem. We can't police it out of existence. I'll introduce you to the team." His team turns out to be a few officers. Just two of them, Det Con Mike Wright and Det Sgt Ohren, working on the operation from start to finish.

"The case has taken over our lives," says Det Con Wright, a slim young detective with impeccably gelled hair. Det Sgt Ohren nods.

'A family business'

They take me through the case. At first, it is almost impossible to grasp the size of it. There are hundreds of potential victims and so many defendants that the case has been split into two trials at Birmingham Crown Court.

The barrister leading the case is Caroline Haughey QC. I meet her at King's Cross station to discuss taking part in the film. Like Det Ch Insp Dale, she sees it as an opportunity.

She simplifies the case for me in the same way as she does for the jury. "This is a family business. Amongst the people involved are fathers, sons, cousins, aunts, uncles, mothers. They share a vision on how they can exploit this commodity.

"The commodity happens to be human beings."

There are five defendants in the first trial: the gang's matriarch, Justyna Parczewska, who met slaves when they first arrived, Marek Brzezinski, who organised housing for the captives, Marek Chowaniec, who got them into the country, his close friend Julianna Chodakiewicz, who arranged work for them, and Natalia Zmuda, who stole their wages.

As I film them entering and leaving court they in turn hide their faces, abuse and threaten me.

Ms Haughey shows them no sympathy. "This case is taking down a very large organised crime group and gouging out its heart."

After the witnesses have given evidence I interview the few willing to waive their lifelong right to anonymity. It's a deeply moving experience. Each time I ask the men a simple list of questions about what happened. Each time a slavery victim breaks down on camera. And yet they are all determined to tell their story.

I ask Piotr Pawski, who was threatened with death by his captors, if he'll ever be free of what happened to him. "I hope so," he replies. "I took part in this programme because I hope there won't be any more cases like mine… I would love to put an end to this and just end the human trafficking."

The pressure on the prosecution team is grinding. They work long hours in a tiny, windowless meeting room. The temperature is stifling. The only change of scene they get is a trip to the courtroom itself. One after another, police and barristers fall ill.

"It's just unrelenting," Ms Haughey tells me over yet another hastily grabbed sandwich. She is pale and has cold sores. "I'm doing 100 hour weeks and my kids hardly see me."

The camera I have chosen for the job is deliberately small and unobtrusive - even so I am very grateful for the police and barristers' patience when I turn it on them during moments of maximum pressure.

As Mariusz is about to give evidence a problem emerges: he is wanted by the Polish authorities on a European arrest warrant. It turns out he was on the run when he fell into the clutches of the slavers. "What would our position be… if I disclose this now?" asks junior barrister Emma Shafton.

"I don't really see the problem," replies Ms Haughey. "Our position has always been - and one of the complainants even said - he was specifically targeting people who came out of prison, people who are homeless."

I watch Mariusz on the stand. He is a star witness, winning over the jury with his honesty about his past, his humility and his frankness about the horror he lived through.

Afterwards Ms Haughey goes down to thank him, as she does every witness in the case. "Well done in telling your story. Getting that part of your life back because now you own it. You really did well, so thank you."

The jury foreman delivers the verdict like a bowler knocking over a row of skittles. The slavers are guilty on every single count. After passing sentences ranging from three to 11 years, Judge Mary Stacey gives Det Sgt Ohren and Det Con Wright an official crown court judge's commendation - some return on four years of their life.

In a later trial three other slavers, including the gang's patriarch, Ignacy Brzezinkski, are sentenced to a total of 20 years.

The convictions please all of the slaves I meet. This does not mean that they can put the experience behind them. "They got big sentences which is great," says Adam Scczepankiewicz. "But I know they [are] seeking revenge. And for the rest of my life I'll be looking back - and worried they will find me and they will kill me."

Things do not end well for Mariusz.

A few weeks after giving evidence his past catches up with him. He is arrested and flown back to Poland to serve a year for robbery.

At least he has the comfort of knowing that his former captors will be inside for far longer.

Panorama, The Hunt for Britain's Slave Gangs - Thursday 5 September at 21:00 on BBC One or catch up on the iPlayer.