The 'Brown Babies' who were left behind

Lesley York

Lesley YorkWhen Babs Gibson-Ward was born in 1944, her mother's navy officer husband did not question whether he was her father.

"He honestly believed I was his child, I think because my complexion at that time was very fair. It took six months for it to change," she said.

She was one of 2,000 mixed race babies born to white British women and black American GIs during World War Two.

The children were dubbed "Brown Babies" by the media and many had troubled childhoods.

When Mrs Gibson-Ward's skin darkened, her mother's lie was revealed - her real father was a black US Airforce engineer.

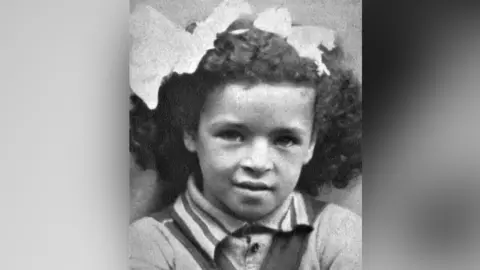

Babs Gibson-Ward

Babs Gibson-WardSent away from her family in Ipswich, Suffolk, she lived in a children's home for the next four years. A foster family came forward and it seemed like a new start. She settled in well but was racially abused.

"I'd never seen anyone that looked like me in the area and sometimes when I wanted to play outside with other children their parents wouldn't let them."

A teacher gave her jigsaws rather than spellings, saying she "didn't have the same ability to learn".

Her family life deteriorated too. She remembers always being hungry. Her foster mother died and her foster father molested her.

Aged 10, she was removed and placed in another children's home. Three years later, her mother came back and they moved to York. But she frequently beat her and ignored her teachers who flagged up her musical abilities.

She found herself on the streets at the age of 15, with no qualifications and no job.

Lesley York

Lesley YorkIt is a familiar story for the so-called "Brown Babies", who grew up in white areas, on the south coast, in the South West, south Wales, East Anglia and Lancashire.

Their fathers were some of the 240,000 African-Americans who were among three million US troops that came over for the war.

Black men were segregated and tasked with manual labour. They built airbases, including Lakenheath and Mildenhall.

They brought candy, Coca-Cola, cigarettes, nylon and new dance moves to British shores.

"Many British people had never seen a black person before. They were charming and less arrogant than the white officers.

"They met women at dance halls or pubs, on evenings which were designated 'blacks only'," Lucy Bland, Professor of Social and Cultural History at Anglia Ruskin University, said.

But relationships were forbidden and their children were often kept secret. Most had never shared their stories until Prof Bland found 45 of them for her book, titled Britain's Brown Babies.

Nearly half had been put in children's homes. Some grew up with their mothers but still faced abuse. Most were lied to about their fathers.

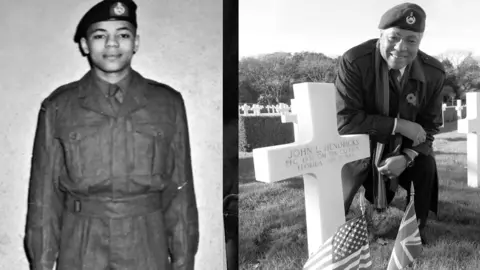

Terry Harrison was one of twins born in 1944 to a Welsh woman. Their mother was spat at by neighbours who banged on dustbins as she walked by.

Aged nine, he discovered his unloving stepfather was not his real dad. He recently found his birth father's grave at a US cemetery, calling it a "wonderful experience".

Very few were adopted. Officials said it would be impossible to place mixed race children and the government blocked adoptions from the US, despite great interest.

Only one of the 45 the author interviewed was brought up by his father. Corporal Leon Lomax arrived back in Ohio at the end of the war with a confession for his wife Betty.

He had fathered a baby, also called Leon, in Chelmsford, Essex. With great difficulty, he managed to have his son flown to the US.

Leon Lomax

Leon LomaxMany struggled with relationships, citing their dysfunctional childhoods as a possible cause, though some have found a sense of belonging.

Monica Roberts was born in 1944 in Liverpool to a single mother who refused to give her up. She was told her skin was dark because she played outside.

As an adult, she tried to find her father but he had already died. However, his sisters sent her photographs and she now feels "a deep connection" to him which has transformed her life.

Monica Roberts

Monica RobertsThe term "Brown Babies" is a self-definition for a number of the group, according to Prof Bland.

With the group now aged in their seventies, she said she wanted to tell their stories before it was too late.

Several have thanked her for finally giving them a voice.

Babs-Gibson Ward

Babs-Gibson WardAs for Mrs Gibson-Ward, encouraged by a former music teacher, she moved to Liverpool aged 18 and trained as a children's nurse. She studied for a masters degree in midwifery, taught at university and later gained a second masters in music.

The 74-year-old teaches the flute in Liverpool, where she lives with her husband.

"I thought everything was hopeless when I was growing up," she said.

"I could definitely have had an easier route but I have learned so much and it hasn't stopped me from doing the things I love."