HMS Victory: The English Channel's 'abandoned shipwreck'

Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc

Odyssey Marine Exploration, IncTen years ago, historians hailed the discovery of HMS Victory, found on the seabed 50 miles (80km) southeast of Plymouth. Its sinking in 1744, which claimed the lives of 1,100 sailors, is considered the worst single British naval disaster in the English Channel. Why have efforts to raise the ship become the focus of a legal battle?

"It was the wreck that every wreck-finder wanted to find," says diver Richard Keen, who began searching in 1973 for Victory, the predecessor of Admiral Lord Nelson's more famous namesake ship.

The professional diver, from Guernsey, grouped together with five others to scour the seabed for two months near Les Casquets, a group of islands eight miles (13km) west of Alderney, the northernmost Channel Island.

The group did manage to locate the wreck of passenger steamer Stella, which sank in 1899 claiming 105 lives, but HMS Victory remained elusive.

Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc.

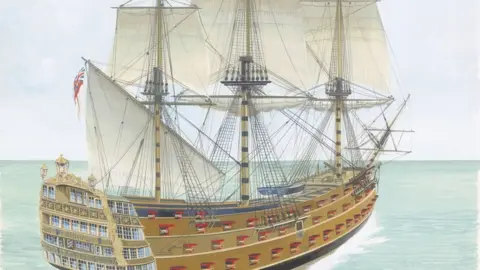

Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc. The 100-gun ship was launched in 1737, and seven years later it was the flagship of Admiral Sir John Balchen as he successfully led a force to relieve a British convoy trapped by a French blockade of the River Tagus, in Portugal.

But on the return journey, Victory was separated from the fleet and sank with all hands on 5 October 1744.

Its exact location in the English Channel would remain a mystery for more than 250 years.

Search efforts initially focused on the infamous Casquets - where the ship was thought to have been wrecked due to poor navigation.

But in 2009, Florida-based Odyssey Marine Exploration announced it had discovered Victory, 62 miles (100km) away from those rocks, suggesting a fierce storm rather than a navigational error had been behind the sinking.

As with the Mary Rose, the Tudor warship which was raised in 1982, there was great public interest in the find.

Built during a period of British naval ascendancy, Victory and its more famous successor were two of the most expensive and grandest ships of the period.

Chris Stephens

Chris Stephens"It was a time when the Royal Navy's power was absolutely central to British power, the growth of its maritime empire, and its prosperity," says Matthew Sheldon, executive director of heritage at the National Museum of the Royal Navy.

"It would be hard to overstate how important they [both ships] are, I think."

The wreck of the Mary Rose would go on to yield 19,000 artefacts of great historical significance but of no private commercial value, because of laws governing sovereign naval property.

But bringing Victory's treasures to the surface would be a costly exercise - one companies like Odyssey would usually fund through the sale of artefacts.

Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc

Odyssey Marine Exploration, IncDespite the majority of the wreck lying some 75m below the surface, two of Victory's bronze guns, a giant 42-pounder and a 12-pounder, have been brought up from the deep with the permission of the government.

The discovery of the larger gun - only carried on a first-rate vessel of Victory's size during the first half of the 18th Century - enabled archaeologists to identify the wreck.

As the only first-rate warship with an intact collection of bronze cannon, Victory's guns provide a unique snapshot: soon after such weapons would be made of iron, and naval tactics would shift.

In addition to the cannon, rigging, glass bottle fragments and remains of the hull and anchors also form part of the wreck.

A massive gold hoard rumoured to be aboard Victory has, however, not been found and its presence on the ship in the first place has been disputed by historians.

There is still more to be learned from the ship, Mr Sheldon says, but the question remains - should that be done through surveying the site underwater, or should Victory rise again?

Maritime Heritage Foundation & Odyssey Marine Expl

Maritime Heritage Foundation & Odyssey Marine ExplHMS Victory: A timeline

- 1726 - Construction of Victory begins in Portsmouth

- 1737 - Victory is launched, later becoming the flagship of the Channel Fleet under Sir John Norris

- 1740 - War of the Austrian Succession breaks out, with Britain siding with Austria's Habsburg alliance against a number of countries, including France and Prussia

- 1744 - Victory relieves a British convoy, trapped by a French blockade in Portugal - on its return, the ship becomes separated from the fleet and sinks on 5 October

- 1765 - HMS Victory, Lord Nelson's flagship and successor to the vessel, is floated out of dock at Chatham

- 1805 - Victory fights at the Battle of Trafalgar, which ends Napoleon's plans to invade Britain but also sees the death of Nelson

- 2009 - Odyssey announces it has found Victory, later suggesting it sank due to a violent storm coupled with the ship's top-heavy design, gun-crowded upper decks and possibly rotten timbers

One man who is convinced Victory's artefacts are best taken out of "harm's way" is Dr Sean Kingsley, a marine archaeologist for the Maritime Heritage Foundation (MHF), which was gifted the wreck site in 2012.

He would like to see artefacts brought up and displayed in a UK museum.

"The government believes this unique wreck can be managed untouched, 80km offshore, in one of the world's busiest sea lanes.

"An irreplaceable piece of British history ends up abandoned, out of sight and mind, with the government's stamp of approval."

Not only that, the site is at risk of damage from fishing trawlers, erosion and illegal salvage, something noted by the Ministry of Defence (MoD) in 2014, he explains.

While the extent of threat to the wreck from fishing and looting is disputed, Dr Kingsley is concerned a 2018 decision to put the foundation's initial 2014 "research and rescue" application on hold will mean the site could be further threatened.

Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc

Odyssey Marine Exploration, IncWhile there is a consensus on the historical importance of the wreck, not everyone in the archaeological world agrees with the Maritime Heritage Foundation's plans for the site.

"This is basically a grave - this is the last resting place of 1,100 British sailors and it should not be disturbed lightly," says Robert Yorke, chairman of the Joint Nautical Archaeology Policy Committee.

"You don't go into a local churchyard and start digging them up hoping you're going to find some gold underneath the bodies."

You might also like:

Mr Yorke has been a long-term opponent of the foundation's plan to excavate the wreck site, saying the project lacks adequate funding, facilities and a museum willing to house artefacts.

He also says the foundation's contractors Odyssey Marine are motivated by profit. This is a claim the foundation rejects, pointing out that selling artefacts to fund the project would be illegal.

Encountering human remains is "a daily part of archaeology", the foundation says, and can be dealt with sensitively. When a skull was found on the Victory wreck, work immediately stopped and the MoD was informed, it says.

Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc

Odyssey Marine Exploration, IncDespite Victory's unique history and concerns over fishing, looting and erosion, in September the wreck site was declared "environmentally stable" and ordered to be "left in situ", according to the MoD and the Department for Digital, Culture Media & Sport.

In addition, Unesco rules do not allow for items to be removed from the wreck, the government departments said in a document lodged with the foundation's licence application.

This decade-long saga faces a further twist though, as the foundation has now been granted permission to launch a judicial review of the government's decision not to allow preliminary archaeological work on the wreck.

The launch of legal proceedings at the Royal Courts of Justice on 6 February has been acknowledged by the MoD, which said it was inappropriate to comment further on the case as it was "subject to ongoing litigation".

For Dr Kingsley the current impasse means "nobody wins".

"After 10 years of lengthy dialogue between the MHF, Odyssey and government, a most likely outcome is a no-deal farce," he says.

"The foundation is convinced the Victory's artefacts are best taken out of harm's way for display in a major UK museum for all to enjoy and learn from."