More children in England at risk of abuse or neglect

Getty Images

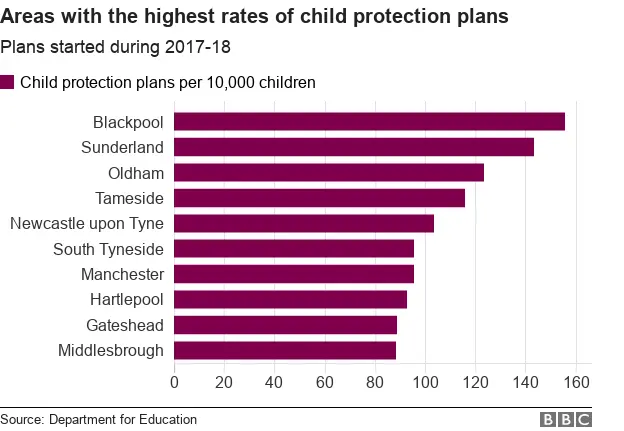

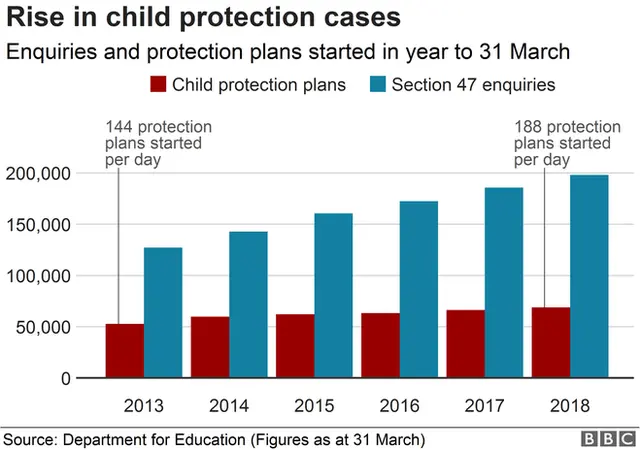

Getty ImagesAn average of 188 children a day in England are being put on protection plans because they are at risk of abuse or neglect, official figures reveal.

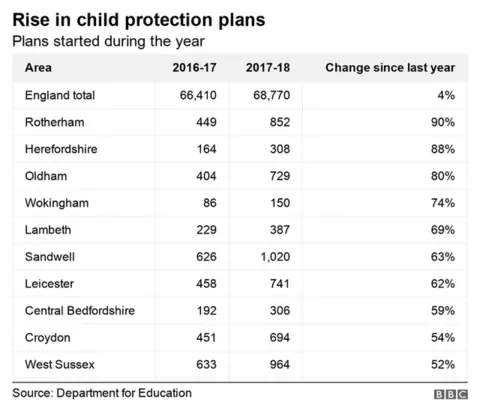

Councils started 68,770 child protection plans during 2017-18, a rise of 2,360 in a year.

The Local Government Association (LGA) said councils were "pushed to the brink by unprecedented demand".

The government claimed the figures showed families were getting the support they needed.

Child protection plans are drawn up by councils to set out how a child can be kept safe and what support can be offered to families.

In 2017-18, there were 198,090 investigations into possible harm, up 56% since 2012-13.

Experts in social work and family rights say more support needs to be given to families before investigations are launched as families report feeling "frightened and anxious" when facing enquiries.

Why are investigations on the rise?

Councils say the rise can be explained in part by greater public awareness and willingness to report abuse following recent high profile cases, combined with more families struggling because of cuts in early intervention services designed to provide support.

They say the rising workload is putting them under further financial strain.

Councillor Anntoinette Bramble, who chairs the LGA's children and young people board, said protection plans were intended to help families where children were at risk of significant harm.

"This is being put at risk by the huge and increasing financial pressures children's services is now under, with many councils being pushed to the brink by unprecedented demand," she said.

"Councils have done all they can to protect spending on children's services by cutting services elsewhere and diverting money, but despite this they have been forced to reduce or stop the very services which are designed to help children and families before problems begin or escalate to the point where a child might need to come into care."

'We were guilty until proven innocent'

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAndy and his wife were investigated by social services when they took their nine-week-old baby to hospital in Sheffield with a bump on the head.

Andy's wife, who does not want to be named, was carrying the boy when she tripped on the stairs.

They rushed the child to hospital, bringing his sister too, and a scan picked up an "anomaly"; some fluid on the brain.

The hospital called social services about a "possible non-accidental injury" and an investigation was launched.

"We were in shock, we couldn't believe it," Andy said. "Social services kept on saying my son had an 'injury' rather than an 'anomaly'."

During the investigation in 2013 social services decided both babies could not return home and needed to remain in hospital. If the parents did not comply, social services said they would issue a court order.

"We were living in fear of losing them. We were guilty until proven innocent," Andy said.

The family remained in hospital for four days waiting for an MRI scan which showed the anomaly was natural and not caused by injury, and the family were allowed home.

In a letter Sheffield City Council acknowledged the situation was "distressing and upsetting" for the family and accepted its handling of matters was "not without fault".

However the council stressed it was "clearly under a duty to make enquiries and to take measures to protect both children" until the exact nature of the anomaly in the child's skull was identified.

What does a child protection plan do?

If they have causes to suspect a child is suffering or likely to suffer "significant harm", social workers make enquiries supported by police, health professionals, teachers and other professionals. These are known as Section 47 enquiries.

The social workers will get a picture of the children's circumstances and then decide if they are likely to suffer significant harm.

If a child protection plan is set up, this determines how the child will be kept safe, how things can be made better for the family and what support can be offered.

If authorities are concerned a plan will not keep a child safe, or it is not working, the council may decide to take the child into care.

What is the effect on families?

Social work expert Andrew Bilson told the BBC councils were increasingly "fire-fighting and responding rather than looking for ways to prevent harm and support families".

The University of Central Lancashire professor said: "We've had a steady rise in the number of investigations. More referrals are leading to an investigation and that's linked to cuts in family support.

"Instead of helping families prevent the need for an investigation, more children are being investigated.

"Even though the number of child protection plans has risen, the number of investigations has risen further. So we're getting more investigations that find nothing.

"Investigations can be harmful in themselves. Either families do not get offered help because the authorities have gone in with the view that they are harming the children, or they don't want to accept it because they think they are being blamed."

Cathy Ashley, chief executive of the Family Rights Group charity, said: "Many families report feeling frightened and anxious when their children are the subject of a child protection enquiry, especially if they don't understand why children's services are investigating.

"Parents may have been the ones initially approaching a doctor, health visitor or social worker for support, and then feel that the child protection enquiry is them being punished for having been open and telling the professionals about being subject to domestic violence or their children's behavioural problems.

"Some parents try to keep it quiet and fear turning to relatives or friends for support because of the stigma and shame they associate with social workers being involved in their lives."

However the LGA said it was important to note child protection plans "don't remove children from their families; that only happens when a child is taken into care".

"If anything, the rise in child protection plans, which is greater than the rise in looked after children over the past decade, is an indication of how hard councils are working to try and keep kids with their families wherever possible," it said.

The Department for Education said the government was improving the system so at-risk children were identified sooner.

Children and families minister Nadhim Zahawi said: "We know there are pressures on councils, but today's data shows more vulnerable children and families are getting support to meet their needs."