Bureaucats: The felines with official positions

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA cat's life typically consists of sleeping, interspersed with eating and the occasional manic bout of skittishness, followed by a good old nap. But some of our feline friends actually work for a living and hold down a proper job - in some cases, complete with uniform.

Here are some of England's cats that do more than snooze, eat and sidle around while looking superior.

Post Office cats

Keystone

KeystoneIn 1868 three cats were formally employed as mousers at the Money Order Office in London. They were "paid" a wage of one shilling a week - which went towards their upkeep - and were given a six-month probationary period.

They obviously did their job efficiently as in 1873 they were awarded an increase of 6d a week. The official use of cats soon spread to other post offices.

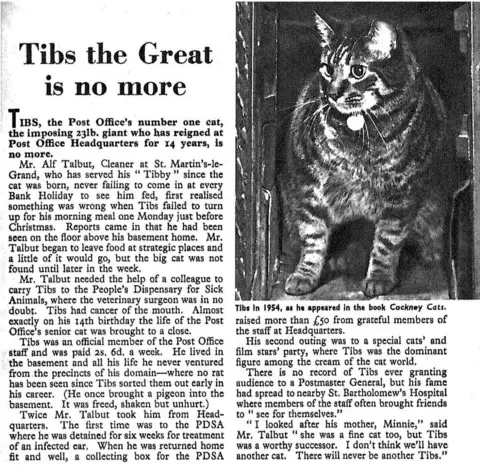

According to the Postal Museum, the most popular cat of all was Tibs. Born in November 1950, at his biggest he weighed 23lbs (10.4kg) and lived in the Post Office headquarters' refreshment club in the basement of the building in central London. During his 14 years' service he kept the building rodent-free.

Post Office Museum

Post Office MuseumThe last Post Office HQ cat, Blackie, died in June 1984, and since then there have been no further felines employed there.

An honourable mention must go to the Belgian authorities, who in the 1870s recruited 37 cats to deliver mail via waterproof bags attached to their collars. It was an idea posited by the Belgian Society for the Elevation of the Domestic Cat, which felt cats' natural sense of direction was not being fully exploited.

During a trial, the cats were rounded up from their villages near Liège, taken a few miles away and burdened with a note in a bag - with the idea the cat would return home complete with missive.

Although all the cats - and notes - eventually turned up, the feline disposition unsurprisingly proved unsuited to providing a swift or reliable postal service and the idea was dropped.

Police cats

Holmfirth Police

Holmfirth PoliceDogs have long been part of the police force, but cats rarely got a look-in - unless they were being arrested for burglary. But in the summer of 2016, Durham Constabulary recruited Mittens.

The appointment stemmed from a letter written by five-year-old Eliza Adamson-Hopper, who suggested the force add a puss to its plods.

"A police cat would be good as they have good ears and can listen out for danger. Cats are good at finding their way home and could show policemen the way," she said.

Mittens is not the only police cat. Oscar lives at Holmfirth Police Station in Huddersfield, where his job involves being "a therapeutic source of support for my officers", and Smokey is a volunteer welfare officer at Skegness Police Station.

As a spokesman from the station said, "being a police officer can be very fast-paced and stressful job so when we need to take a break or grab some air now, many of us pop outside a spend a few minutes with Smokey".

Skegness Police

Skegness PoliceShowbiz cats

Hulton Archive

Hulton ArchiveWhether it's showing off in feature films, flogging luxury pet food to besotted owners, or chilling out on the set of Blue Peter, there has long been a place for cats in front of the camera.

Arthur was the furry face of Spillers cat food for nearly 10 years from 1966, scooping Kattomeat from the tin into his mouth. He was such a star the brand was later renamed Arthur's in his honour. There were rumours that Arthur was made to use his paw to eat because advertisers removed his teeth - but the allegation proved to be untrue. He was just a natural paw-dipper.

Arthur II and Arthur III followed the original.

Blue Peter's Jason, a seal point Siamese, was the first in a long line of presenter pusses on the popular BBC children's programme. Others included Jack and Jill, who became known as the disappearing cats, because of their habit of leaping out of whichever lap they were in whenever they appeared on screen, and Willow, who was the first Blue Peter cat to be neutered or spayed.

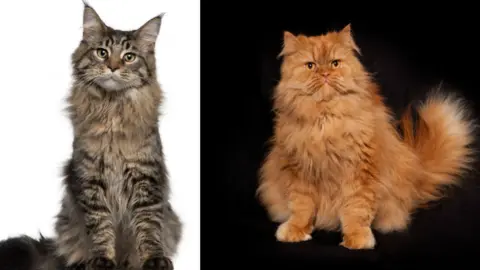

Two red Persians played the role of Crookshanks in the Harry Potter film franchise - Crackerjack was a male and Pumpkin a female - while Mrs Norris was played by three Maine Coons named Maximus, Alanis and Cornilus - each was trained to perform a specific act, such as jumping on to actors' shoulders or lying still.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMuseum cats

British Museum

British MuseumAt some point before 1960, a colony of stray cats found its way to the British Museum and established itself there. Unneutered and untamed, it's estimated that at one point there may have been as many as 100 moggies roaming around.

Records in the British Museum's archive contain reports of kittens being born in the loading docks and running through the bookshelves of the museum library.

The museum eventually decided enough was enough. The invaders were set to be exterminated, but were saved by the museum's cleaner, Rex Shepherd, who set up the Cat Welfare Society and had the strays safely neutered and adopted, until the population was brought down to a more manageable six.

British Museum

British MuseumUnder the guidance of Mr Shepherd, some of the cats, which were kept to control the vermin population, featured in newspaper articles - including a feature on them having their Christmas dinner - and became internationally famous. Suzie could snatch pigeons out of the air to eat them, while Pippin and Poppet were trained to roll over on command.

There are no living cats at the museum today - although there are some mummified ones in the displays. If you're after a live one, try the London Water and Steam Museum, which has Maudslay, a black and white fellow named after an engine, or the Jane Austen Museum in Chawton, Hampshire, where Marmite is on hand (or paw) to greet visitors.

Military cats

Hulton Archive

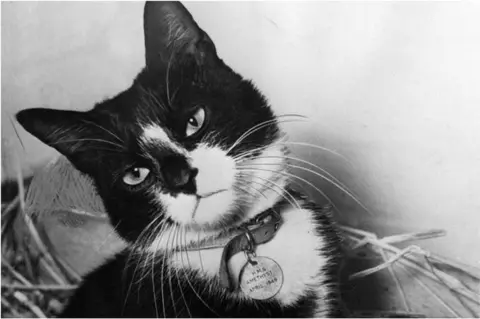

Hulton ArchiveAs far back as 9,500 years ago, cats were used on naval ships and in rat-infested trenches. During World War One, the British Army and Royal Navy deployed nearly half a million to fend off pests on land and at sea.

By World War Two, nearly every vessel had at least one ship's cat.

One of them, Simon, became the only cat to be awarded the Dickin Medal - the animal equivalent of the Victoria Cross - for helping to save the lives of naval officers during the Chinese Civil War in 1949.

While the ship was under siege for 101 days, he was credited with saving the lives of the crew by protecting the ship's stores from an infestation of rats.

The brave chap suffered severe shrapnel wounds when the ship came under fire and was given a hero's welcome when it eventually returned to dock in Plymouth. Simon lived long enough to get back to England, but died in quarantine three weeks later. He was buried in Ilford, Essex, with full military honours.

PA

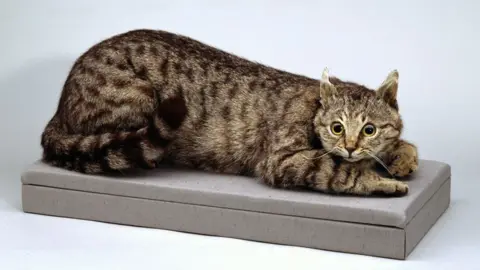

PAAnother wartime hero was Crimean Tom, also known as Sevastopol Tom, who saved British and French troops from starvation during the Crimean War in 1854.

The regiments were occupying the port of Sevastopol and could not find food. Tom could. He led them to hidden caches of supplies stored by Russian soldiers and civilians.

Tom, who was taken back to England when the war was over, died in 1856, whereupon he was stuffed. He is now a permanent part of the National Army Museum in London.

National Army Museum

National Army Museum