Zoo attacks and the people who survive them

Alamy

AlamyZoo attacks in the UK are thankfully rare occurrences. But occasional lapses in safety, horrific though they are, have led to some remarkable survival stories. BBC News Online investigates.

The use of untrained teenagers as animal keepers in British zoos would send shivers down the spine of health and safety executives today.

But the practice was remarkably common during the 20th Century when small zoos sprang up in towns and cities across the country.

'It was fabulous, until the accident'

Alamy

AlamyRichard McCormick , who now lives in Harrogate but grew up in Coventry, got a job at the city's Whitley Zoo in 1966, not long after leaving school.

"At first, I looked after the parrots," he said. "Then, after a few weeks, they gave me the elephant, the bears and Harry the hippo to look after."

Despite his rapid introduction to the work, he enjoyed the job.

"It was fabulous until the accident," he said.

One of his duties was cleaning out the hippo's cage.

"I used to go and give him a scrub with a big brush," he said.

"As I opened the door to his cage, a safety barrier was supposed to come across but one day it was broken. The heavy door flew open and hit the hippo up the bum," Richard said.

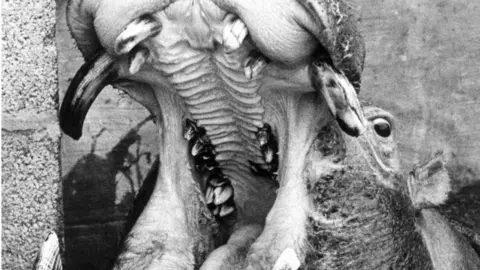

The three-tonne creature turned towards him furiously.

Richard McCormick

Richard McCormick"He grabbed my head between his jaws and dragged me off into his pool," Richard said.

"I felt my ribs crack. I was scared to death - I thought I was going to die."

Richard's body was hanging from the hippo's jaw where - a few weeks previously - Harry had had a tusk removed after contracting toothache.

"If that hadn't happened, his tusk would have gone right through my body," he said.

Luckily, the head keeper John Vose heard Richard's screams.

"As Harry emerged from the water, John hit him with an iron bar," he said. "He opened his mouth and dropped me. I scrambled out of the water and over the wall to safety."

Richard was rushed to hospital. "I was screaming, thinking my back was broken," he said. "But it was my ribs and my collarbone and I also had a punctured liver."

It took Richard two months to recover. Meanwhile, he became a celebrity. His face appeared in all of the national newspapers, which claimed he was the only British person to survive a hippo attack.

He still bears the marks from the hippo's teeth on one side of his body but says he bears it no ill-will.

"This story has followed me all my life," he said. "At the time, I received letters from all over the world."

'They were going crazy'

Tyne and Weird

Tyne and WeirdJanet Coghlan lived near Seaburn Zoo, in Sunderland and as a 13-year-old, she took on a Saturday job there.

"I'd always loved animals and it filled in time during the summer holidays," she said.

At first Janet and her friends took money on the kiosk and chopped fruit for visitors to feed the monkeys.

"With hindsight, the zoo was an absolute disaster area," Janet said.

"I used to feel sorry for the animals. They were penned into very small cages and the place was very barren - like a concrete jungle."

The zoo had formerly been an ocean park and the tigers were kept in a former swimming pool and a railway carriage.

"They were going crazy in there - pacing up and down," Janet recalled.

Tyne and Weird

Tyne and WeirdOne day, in August 1978, Janet was asked by the zoo's owners to help them clean out the pit where a 13-month Bengal tigress cub called Meena was holed up.

"They used to get us to wash out the cages with a hosepipe," she said. "It was a ridiculous job to give to a child.

"There was a wire between me and the tiger but nothing much else.

"The zoo owner's wife asked me to hold the gate to the pit open while she brought the tiger out on a chain.

"The tiger had been penned up for goodness' knows how long and as she came out, she reared up on her back legs like a dog being brought out for a walk.

"She came down on me and I fell in the mud."

AFP

AFPThe 12-stone cub began to claw at Janet's face.

"I remember thinking I wasn't going to get away," she said.

"Somehow I managed to crawl out of her reach. I was absolutely covered in blood."

The cub had ripped open Janet's face, the wound running down her right cheek from under her eye to her jaw.

"It was over so quickly, I didn't actually feel the pain of it. Crazy though it sounds, I'd say a paper cut hurts more," she said.

"I needed 250 stitches in my face and head. My face was so swollen, they had to liquidise my food so I could eat.

Janet survived the attack, she believes, because the cub was just "playing" with her.

She said her parents were "horrified" when they found out about the attack but decided not to prosecute the zoo owners. "The zoo closed shortly afterwards," she said.

Although her scars have faded to the point of being invisible to the casual observer, for Janet they are the first thing she sees when she looks in the mirror.

"I'm quite open about what happened - it doesn't upset me," she said.

The main thing that distresses her as an adult is the treatment of animals in captivity.

"I'm involved with the Born Free Foundation and I don't think animals should be in captivity at all," she said. "They should be out in the wild, where they belong."

'I wound down the window to stroke a lion'

PA Archive

PA ArchiveGlenys Newton clearly remembers her excitement when her family borrowed her Uncle Meirion's maroon Austin Cambridge so they could make a day trip to nearby Longleat Safari Park, in Wiltshire, in 1969.

"There were nine of us crammed in the car - four adults and five children," she said. "My dad was driving and, as we drove through the animals, he let me sit on his knee."

Glenys, then aged five, remembers her mother being excessively careful about looking after the car.

"We weren't allowed to eat our sandwiches inside," she said. "The irony is that when we reached Longleat, Mum didn't want us to drive through the monkey pen in case they took bits off the car."

Instead, the family headed for the lion enclosure. "We parked up and there, sitting by the window, was an enormous lion with this beautiful mane. He was really gorgeous," she said.

"He was just next to the car window, waiting to be patted."

Glenys Newton

Glenys NewtonWhile the adults were talking among themselves, Glenys began to wind down the car window.

"I got it about halfway down," she said. "My dad was not prone to panicking but I still remember the feel of his rough hand on mine and the feel of the fear coming through him as he placed his hand on top of mine to wind the window back up."

The lion, however, was not impressed. "He let out an enormous roar," she said. "I sat face to face with this roaring lion, blissfully unaware."

The brief encounter provoked a frenzy among the big cats and five or six of the animals climbed on to the car. "They were climbing on the window and the bonnet," Glenys said.

"My brother remembers a hissing sound as they punctured the tyres and the car tilting to one side. It was the first time he saw adults feeling afraid."

PA

PABut the little girl who had started all the trouble was oblivious to the panic around her. "I remember matching my hand up to one of the lion's paws as it climbed over our window. They were my friends and I don't remember feeling any fear at all," she said.

"My dad was parping on the car's horn, which is what we had been instructed to do if we got into trouble, but the park rangers must have been on their lunch break."

At last, the rangers appeared in a zebra truck to tranquilise the animals. "I thought they had killed them and was beside myself," Glenys said.

The family's story featured in several national newspapers. "My mother wrote to the Marquess of Bath, who runs Longleat, asking for the ticket money back but he wrote back saying he didn't know what all the fuss was about."

Today, Glenys still visits safari parks and retains her love of wildlife.

"I think at the time people didn't appreciate these are wild creatures," she said.

"Maybe they imagined the animals had been specially trained not to eat you."

'Never risk-free'

Standards in zoos have changed a lot since the 1960s and 70s, according to Sarah Wolfensohn, a professor of animal welfare at the University of Surrey.

Surprisingly, however, she says the licensing standards remain "relaxed".

"Licences are issued by local authorities," she said. "The good zoos are really good but there is a spectrum of standards. Bad management often goes along with poor animal welfare."

Since 2013, there have been two high-profile keeper deaths in the UK. Sarah McClay was killed by a Sumatran tiger at South Lakes Wild Animal Park in Cumbria, while Rosa King died in 2017 at Hamerton Zoo Park in Cambridgeshire.

"Mistakes happen and sadly things go wrong," said Prof Wolfensohn.

"Zoos and safari parks are never completely risk-free places and it is unreasonable to expect that they would be."