Malkinson and McCarthy: The shock and surrealism of captivity

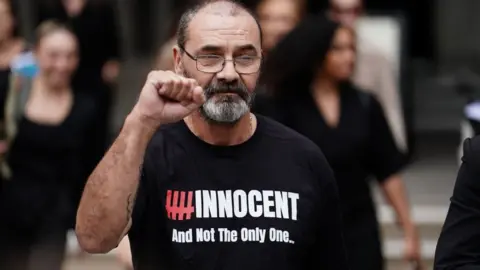

Both Andrew Malkinson and John McCarthy have been deprived of their liberty. One spent 17 years in prison for a crime he didn't commit, the other was held hostage for more than five years.

When he was invited to guest edit Radio 4's Today programme, Mr Malkinson asked to meet Mr McCarthy. Face-to-face they discussed the "shock and surreality" of having been prisoners.

From the confines of his British prison cell, Andrew Malkinson would lose himself in astronomy books.

"What's it like to be a light beam, travelling for over 1,000 years to get somewhere?" he would wonder.

He said reading would offer some brief escape from the grim reality of being behind bars after being wrongfully convicted of rape.

"You can bang on the walls, you can scream and it won't make any difference... so you retreat into your own mental space," the 57 year old said.

He was released in 2020 on a strict life licence, but it would take another three years until he was finally cleared by the Court of Appeal. Advances in forensic testing had linked another man to the crime.

PA Media

PA MediaBooks were more of a rarity for John McCarthy, a journalist who was held hostage in Lebanon between 1986 and 1991. But, occasionally, one would land in his cell with a welcome thud.

Once his captors had left, he was allowed to pull his blindfold down and would eagerly take a look. "If you got a thick book, that would be brilliant," he said.

At one point he got the novel Vanity Fair, which he described as "a treasured possession". Mr McCarthy and his cellmate Brian Keenan eagerly read the hefty tome as quickly as possible, knowing it could be snatched away again at any moment.

"To lose yourself into a story was amazing," he said.

Less popular was a copy of "The Complete Guide to Breastfeeding". "I think Brian read it, I'm afraid I didn't," Mr McCarthy explained.

'This cannot be happening to me'

During their conversation, Mr Malkinson and Mr McCarthy discussed how surreal it felt to be held prisoner while knowing they had done nothing wrong.

Both men described repeatedly thinking, "this cannot be happening to me".

As the civil war in Lebanon escalated, Mr McCarthy had been trying to get to the airport to fly home when he was bundled out of the car at gunpoint by Islamic Jihad militants.

He described how his initial "bubble of denial" was punctured by "a sense of dread and shock" once he was left alone in a filthy underground cell.

"I realised there is no handle on the inside of a cell door... and that really hit me," he said.

BBC/Overs

BBC/OversEven though Mr Malkinson knew why he was being arrested, he said he recognised that same sense of bewilderment.

"I said to myself, 'this is going to end soon - it has to, they've got the wrong guy'."

That was in 2003 when he was 37 - it would take 17 years for him to be released.

During the interview, Mr McCarthy said he had been struck by the fact it was Mr Malkinson's olive skin which helped make him a police suspect, while Mr McCarthy's blonde hair had been the reason he was targeted, according to a guard he once asked.

Mr Malkinson's conviction had hinged on identity evidence, including being picked out of a video parade he had volunteered to take part in.

"My blonde hair and your darker skin put us in the frame for total shock and surreality," said Mr McCarthy.

The Court of Appeal's decision to clear Mr Malkinson came after DNA evidence - found by charity Appeal in 2021 following advances in science - implicated another man in the crime. No forensic evidence had linked Mr Malkinson to the attack.

'I'm happier when I'm not here'

As the years passed for Mr McCarthy he "desperately thought of getting back to London, to the Home Counties, to family and friends".

"England was my choice of destination," he explained to Mr Malkinson.

"But that's because I got away from them [the kidnappers]. You were still here [in the UK] and they were still trying to deny you the justice that you were after."

In contrast, for Mr Malkinson, being released did not feel like a homecoming.

"I don't hate this country, but it doesn't feel like home to me, it feels like I've been betrayed very badly," he explained.

Despite his release in 2020, he still felt the weight of being a convicted sex offender until he was finally cleared this year.

"You're walking the streets but you're far from free," he said.

Andrew Malkinson is guest editor of BBC Radio 4's flagship news and current affairs programme on 29 December.

Mr McCarthy had never left Europe before his fateful foreign assignment to Lebanon in 1986 - whereas by the time Mr Malkinson was arrested in 2003, he had travelled extensively and used those memories to keep him going.

In prison, he dreamt of his travels in South East Asia and told himself he would return to Railay Beach in Thailand.

"I'd revisit it in my mind when I was incarcerated [and think] 'I have to go back there. If I ever get evidence to prove I'm innocent, I'm going' - and it helped."

Now his conviction has been overturned, travelling to far-flung places is back on the cards, though he is still waiting for his government compensation.

Ministers said they would end the practice of deducting prison board and lodging costs from pay-outs after a public outcry after he was cleared. But Mr Malkinson told Today the compensation rules were "still grossly unfair" as the change did not apply to people affected by earlier miscarriages of justice.

"I'm happier when I'm not here," he said, having just returned from camping in a pine forest in Turkey. "It feels a bit easier [to be away]… I can breathe."