Homeless children: Living with trauma, tears and tiredness

BBC

BBCWith near record numbers of homeless families in temporary accommodation in England, the BBC has spoken to children and parents about being moved from place to place.

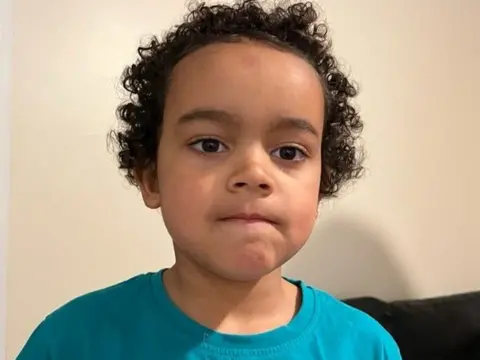

Koby Anderson is very tired - so tired that he sometimes sleeps at school "in the head teacher's office", says his mother Lily.

For six months, the six-year-old has been living in the same bedroom as his mum and one-year-old brother Isiah, who wakes during the night "a lot", says Koby.

The family is crammed into a one-bedroom flat in Bristol, having been made homeless in September. It has been provided by the council and they cannot bring their own furniture because they could be moved on any minute.

"I enjoyed the other house that we lived in, but this one is a squeeze and a squash," says Koby. "I do miss my bunk bed. Under my bed is a wooden bit where I keep all of the things that are special to me. Hundreds of cards, in my special box. I didn't think it was safe enough to bring them here."

'No-fault' eviction

Lily says her son refuses sleepover invitations at his friend's house as he is scared the family will lose their accommodation. "He had a nightmare the other night because he thought he was going to be on the streets. I've obviously told him that's never going to happen but he said 'in my dream I was in a sleeping bag, you were next to me and we were sleeping on the streets'.

"He's had night terrors, bed-wetting. He's been referred to the mental health team. It's had a massive impact."

The family's story is not uncommon. They were initially made homeless as a result of a "no-fault" eviction, because their landlord decided to sell. In its 2019 manifesto, the government promised to ban these types of evictions, but has not yet done this.

Lily, a part-time nurse, failed to find an alternative property because rents had soared. In any case, says Lily, the fact her salary is topped up by universal credit means "letting agents don't give me a look-in, they want couples". With 19,000 households on Bristol's social housing waiting list, temporary accommodation was the only option.

They spent the first eight weeks in two Travelodge hotels, without access to cooking facilities, living off takeaways or the generosity of friends. "We had to check out every week," says the 29-year-old. "We'd take all the suitcases to the car, and Koby would be screaming and crying because he didn't want to go to school, as he didn't know where we were going to end up."

Lily would spend the day waiting to hear from the council about where they would be sent - often back to the same hotel. Their current property, in a block of 12 flats all housing homeless families, is an improvement on hotel living, but is certainly not a permanent home.

The latest official figures show, at the end of September, almost 100,000 households in England were in temporary accommodation, a near record level.

The figure, from Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, includes more than 125,000 children, thousands of whom live in hotels, bed and breakfasts or other unsuitable properties. Similar figures for Scotland show more than 9,000 children in temporary accommodation, a record high.

'Intentionally homeless'

For many homeless families, temporary accommodation can be anything but.

In Thamesmead, south-east London, seven-year-old Pyper and her mum, Tammy Ebsworth, have been in temporary accommodation for six years after a relationship breakdown left them homeless. They now face more upheaval, even though Tammy is eight months' pregnant.

When the 28-year-old told her local authority their property would be too small when her baby was born, they offered her a bigger place, 60 miles away in Colchester. She turned it down and was told that, consequently, she had made herself "intentionally homeless". They were ordered to leave the property by 14 February and are only still there because Tammy is appealing against the decision.

"If I moved all the way out to Colchester, who's going to look after my daughter when I go into labour?" asks Tammy. "No-one's going to be able to come down and see me. It's too far. I'd need to change hospitals, change doctors, change her school. We're not going to know anyone, I don't know how to get anywhere."

As Tammy talks, Pyper crouches down next to her, drawing and doing maths questions. Dealing with the prospect of moving has been a "nightmare", says Tammy. "She won't be able to see her dad, her nan on a weekend like she does now. She hasn't been sleeping. She's quite a handful at the moment."

"It makes me sad because I will miss this house, miss my family, miss my friends, everything." says Pyper as she doodles a sad face on a piece of paper. "I don't want to go."

Research by homelessness charity Shelter last year suggested homeless children often have to change schools many times or lose more than a month's schooling entirely. Others have fewer than 48 hours' notice that they must move.

In next Wednesday's Budget, the charity wants the government to increase housing benefit, frozen since 2020 while rents have risen by 7.5% nationally.

"If that doesn't happen, it's inevitable that this government is going to preside over a significant increase in homelessness," says Polly Neate, Shelter's chief executive.

The government says housing benefit levels were increased "significantly and beyond inflation" during the pandemic, "benefitting over one million households by an average of more than £600 over the year", while "tens of thousands of homes for social rent" are being built.

On a recent morning, Koby ran out of his block of flats and, seeing it had snowed overnight, made a small snowball that he fired at his mother and brother before laughing heartily - a typical six-year-old yearning for a place to call home.