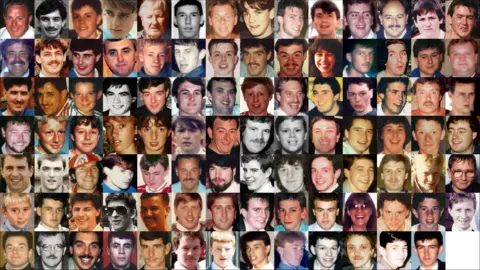

Echoes of Hillsborough for Manchester Arena families

Family handouts

Family handoutsThe Manchester Arena Inquiry was a mammoth undertaking. Evidence was heard over 196 days, presented and pored over by 18 legal teams, and culminating in three reports running into hundreds of pages.

I went to many of the hearings and, while much of what I heard did cast fresh light on the May 2017 bombing, I listened to a lot of the evidence with a sinking heart and a sense of familiarity and deja vu.

As the BBC's North of England Correspondent, I've also spent many years covering the aftermath of the Hillsborough disaster in Sheffield - sitting through two years of inquest hearings, and three criminal trials.

The more I heard at the Arena inquiry, the more it reminded me of Hillsborough.

And I wasn't the only one. Several Hillsborough families told me that they had an uncomfortable sense of history repeating itself.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMargaret Aspinall's son, James, died in the April 1989 disaster - one of 97 Liverpool supporters to have lost their lives. She says seeing what happened at Manchester Arena brought back painful memories. "You saw people were left again without getting CPR. The main thing is… lessons have not been learnt."

I started to keep a record of the ways the two tragedies seemed to overlap - and quickly realised the seeds of disaster had been sown well before each fateful day.

Failures in event planning

At both Hillsborough and Manchester Arena, joint working between the organisations responsible for crowd safety failed. The Hillsborough Inquests found that in the years before the disaster, Sheffield Wednesday FC had not agreed any meaningful contingency plan with South Yorkshire Police - and the club had not been part of a working party, whose other members included South Yorkshire Police, the fire service and local councils.

At Hillsborough, the club's safety certificate was 10 years old, and hadn't been updated despite changes to the ground which had impacted on capacity and stewarding. A document called The Green Guide was relied on by the club. It was a voluntary code with no legal force and open to interpretation.

In Manchester - British Transport Police (BTP), Greater Manchester Police, North West Ambulance Service and Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service were supposed to work together on a joint planned response to an emergency through a local "resilience forum", with meetings every six months.

The Arena inquiry heard that in the two years leading up to the attack, officers from BTP were only present at a third of those meetings, and those who had attended weren't senior enough.

For 5 Minutes On, Judith Moritz looks at the many parallels between the Hillsborough and Manchester Arena tragedies - and asks whether history is repeating itself.

The Manchester inquiry also found the venue's operator SMG UK, and its security contractor Showsec, both had inadequate risk assessments. It also ruled that a breach of the Arena's premises licence - a failure to agree a minimum number of stewards - may have contributed to the fact the attack wasn't prevented.

Companies working at the Arena were also meant to comply with a document called The Purple Guide, which provides important guidance about health and safety at music and other events. The Manchester inquiry found the Arena's private medical provider ETUK "fell a long way short of the guidance provided by the Purple Guide".

Virtually no paramedics

Hillsborough Inquests

Hillsborough InquestsAt Hillsborough, ambulances lined up outside the ground, but only one South Yorkshire Metropolitan Ambulance Service (SYMAS) vehicle was allowed onto the pitch with only one paramedic at the Leppings Lane end.

At Manchester Arena, only one paramedic was inside the foyer for the first 40 minutes. Ambulances arrived outside, but a casualty clearing station was set up away from the area where the bomb went off, and the injured had to be lifted there, rather than being offered help inside the Arena.

At both Hillsborough and Manchester, important life-saving help was given by members of the public.

Not enough stretchers

One of the most enduring images of the Hillsborough disaster is that of Liverpool fans carrying the dead and injured on advertising hoardings used as improvised stretchers, in the absence of the real thing.

The same thing happened at Manchester - with graphic testimony at the public inquiry about what happened to one of the fatalities, 28-year-old John Atkinson, who nearly slid off an advertising board and was then carried out on a section of metal railings.

Family handout

Family handoutPete Weatherby KC is a barrister who has represented both Hillsborough and Arena families. He told me some of the similarities were "pretty shocking".

"Something as basic as stretchers in both Hillsborough and the Arena. People who were very, very severely injured and in some cases died, were carried out on advertising hoardings in both cases, 30 years apart. There has to be a rethink here".

Radio problems

At Hillsborough, the police radio systems failed and officers outside the ground could not hear instructions or communicate. There was a failure to get through to the police control room.

The Manchester inquiry heard evidence that not all stewards had radios, and there was confusion about the functionality of the radios issued to some Showsec staff. Their training in how to use the radios was not adequate.

Wild goose chases

London News Pictures

London News PicturesAt Hillsborough, families desperate for information struggled to get through on jammed phone lines. Many drove to Sheffield to search for loved ones. But on arrival, it was equally impossible to locate relatives - and the way they were treated, added to their trauma.

Barry Devonside was at the match, but not on the Leppings Lane terraces where his son, Christopher, was crushed. Mr Devonside went to the temporary mortuary to look for the 18 year old, but police sent him away. He spent seven hours checking at hospitals and a reception centre before being sent back to the mortuary where his son's body had been lying all along. He then had to look at Polaroid photos of all the deceased in order to identify Christopher.

Twenty-eight years later, the story of Andrew Roussos at Manchester Arena bears a horrible resemblance to that of Barry Devonside. Andrew's wife Lisa - and their children Ashlee, 26, and Saffie-Rose, 8 - had been on a "girls night" at the arena to watch pop star Ariana Grande.

When the bomb exploded at the end of the concert, the three of them were in the arena's foyer. Andrew and his son Xander had been waiting outside nearby to collect them - and were quickly at the scene. But although they found Ashlee straight away, they couldn't find Lisa or Saffie.

The pair walked round and round the perimeter of the arena, leaving their details with police officers and asking for help. They didn't know that they were yards from Lisa, who was lying inside on the foyer floor - or that Saffie had been carried out of a nearby exit and put into an ambulance.

They were sent from pillar to post, travelling between three hospitals, until they finally found Lisa in the early hours of the next morning. But Saffie remained missing for 14 hours, until they were finally told that she'd died in the explosion. At the public inquiry, they learned that she was alive when she was taken out of the arena, and had actually died at hospital.

Survivability

In 2012, the Hillsborough Independent Panel published a report which found that 41 of the victims had the potential to have survived, if the emergency response had been different. Barry Devonside's son Christopher was amongst them. Inquests later found he may have lived for two hours after the match was stopped.

This year, the Manchester Arena Inquiry established that 20 of the 22 people killed in the bombing had died from unsurvivable injuries - but it ruled that it was likely that emergency services' inadequacies had prevented John Atkinson's survival. Inquiry Chairman Sir John Saunders also said he could not rule out the possibility that Saffie-Rose Roussos could have been saved with better treatment.

Family handout

Family handoutFrom impersonal, to personal

The Hillsborough families have endured the double tragedy of the disaster itself, and also a three-decade-long legal aftermath which has included a public inquiry, two sets of inquests and four trials.

The Manchester Arena bombing has generated several reviews and reports, and a public inquiry which lasted two years. The Arena inquiry included learning which came directly from Hillsborough. After the first set of Hillsborough Inquests in 1990, which referred to the victims by number, there was a determined effort to put the victims at the heart of the process second time around.

That's why, in 2014, the new Hillsborough inquests in Warrington began with a "pen portraits" process - with every bereaved family invited to speak in court about their loved ones' lives and characters. The experience was seen as positive, and has since been used elsewhere, including at the Grenfell Tower Inquiry.

The Manchester Arena Inquiry also began with individual pen portrait family tributes to each of the 22 victims - an approach welcomed by the Mayor of Greater Manchester, Andy Burnham, who has also worked with Hillsborough families for many years.

"I think the experience of the Arena families at the inquiry was better than it would have been had it not been for what was revealed about what was so wrong with the original Hillsborough inquests - and how impersonal that was."

Legal hurdles for families

However, not every step of the legal process has been positive for survivors and relatives.

At both the Hillsborough inquests, and the Manchester Arena Inquiry, survivors applied to be given "core participant" status, which would have afforded them legal representation. In both cases, they were denied.

Anne Eyre survived the crush at Hillsborough and it changed her life forever. She went on to become a consultant in emergency planning and disaster management. She established a peer support programme for people affected by the Manchester bombing.

She says using her lived experiences to help others, who aren't legally core participants, is her way of "paying it forward".

"Regardless of your legal status, it's a constant thing of trying to make sense of an experience where some people around you have died, and you have lived. The randomness of it never leaves you".

PA Media

PA MediaThose affected by both tragedies also speak of their experience of enduring months of courtroom argument, as organisations involved at both Hillsborough and Manchester Arena sought to blame each other.

"We see a repeat of this tendency of public bodies not to feel able to tell the truth at the first time of asking," says Andy Burnham, "and sadly, that has repeated, not to the same degree, but to some degree with the Manchester Arena Inquiry."

The Greater Manchester mayor is one of those leading the campaign for a "Hillsborough Law" - which would give families bereaved through public tragedies financial support for legal representation at inquiries.

"It's something we need very urgently. People know that mistakes get made - that's life. What people won't forgive is the covering up of those mistakes.

"And then the pushing of people, already traumatised by their loss, into a wilderness where they're left just trying to fight for change, truth, and answers for years and years to come."

This week, the Government announced the creation of a new role - that of Independent Public Advocate. It's part of an effort to improve care of survivors and families of people killed in major disasters, including by supporting them through the inquiries that follow.

But it stops short of the full package of measures which some would like to see.

"The obvious problem with inquiries and inquests is that very often you get a fantastic report and great recommendations - but then it sits on a shelf," says Pete Weatherby KC.

Both Hillsborough and Manchester Arena have resulted in multiple inquiry reports. One thing that everyone involved in both disasters has in common is the hope that they'll be used as the basis for real change - so no-one else has to go through similar suffering in future.

Follow Judith Moritz on Twitter