How a British special forces raid went wrong, and a young family paid the price

BBC

BBCWhen British special forces raided a family home in Afghanistan in 2012, they killed two young parents and gravely wounded their infant sons. A BBC investigation has revealed that special forces command didn't refer the incident to military police and it was never investigated, until now. In Afghanistan, a family is still trying to heal.

BBC

BBCLate on the evening of 6 August 2012, in the courtyard of a family home in Afghanistan, Abdul Aziz Uzbakzai sat down for the last dinner he would ever have with his son. At the table were Abdul Aziz and his wife, four of their five children, and two of their young grandchildren. It was the 18th night of Ramadan, the holy month when Muslims fast. The family lived together in a modest home in a village called Shesh Aba in Nimruz province.

That day had begun like any other - a shared pre-dawn breakfast, before sunrise brought the fasting hours and family members went to work. Abdul Aziz's eldest son, Hussain, opened the small grocery shop he ran. Hussain's wife Ruqqia cared for their two young boys and began her work in the home. A goat was slaughtered by a neighbour in anticipation of evening meals that would break the day's fast.

The only thing out of the ordinary, according to the family's account, was the arrival of two unknown male visitors. In rural Afghanistan, it is not uncommon to receive unexpected guests, and tradition dictates that they are shown hospitality. But Abdul Aziz felt himself becoming wary of the two men, he said, and he called Hussain to close the shop early and come home.

After sunset, the two guests were given food and ate separately and they left without incident at 10pm, Abdul Aziz said. It was a hot summer night in Shesh Aba, so the family ate outside. At the end of the meal, Abdul Aziz stood up and said he was tired and would go to bed. He said "Goodnight Hussain Jan" - a term of loving affection - to his son, "Goodnight daughter" to Ruqqia, and "Goodnight boys" to the boys.

BBC

BBC

The boys were young then - Imran three and his brother Bilal just one and a half. They do not remember anything now about what would unfold later that night, and the family has tried to shield them in the decade since from the worst of the horror. They know that before bedtime, their father had pulled their mattresses out into the courtyard, because the heat had made their shared room stifling, and that they had fallen asleep with their parents, for the last time, under the stars.

By that point, in 2012, coalition forces had been waging war in Afghanistan for a little over a decade. Elite special forces units from leading coalition countries were regularly carrying out so-called "Deliberate Detention Operations", also known as "Kill/Capture missions". Troops typically flew in by helicopter after dark and launched fast-moving assaults against suspected Taliban targets. For the UK, these night-time raids were usually executed by the SAS or SBS, the highly-respected special forces units of the British Army and Royal Navy.

But unknown to the British public at that time, SAS operatives were already suspected at the highest levels of UK Special Forces of illegally killing Afghan men who had surrendered and been detained, and later covering up the killings with fabricated reports. A BBC Panorama investigation published earlier this year revealed that one SAS squadron killed 54 people in suspicious circumstances in one six-month tour. The pattern led one of the highest-ranking special forces officers in the UK to warn in a secret memo to the head of special forces that there could be a "deliberate policy" in effect to kill detainees, "even when they did not pose a threat".

One of these "Kill/Capture" raids was about to be executed on Abdul Aziz's family home. At about 3am, British military helicopters descended through the dark sky over Nimruz and landed outside the village. Special forces operatives dropped to the ground and moved towards where the family were sleeping. Abdul Aziz was woken by the first gunshots, and within minutes foreign soldiers were in his room, he said, pushing him on the ground, handcuffing and blindfolding him.

"I pleaded with them to let me go to where my son and daughter-in-law and their children were sleeping," Abdul Aziz said. "I could hear my two daughters screaming and pleading for help. No one was helping them. I could not do anything for my children."

BBC

BBC

Chaos had descended on the rural family home. According to his account, Abdul Aziz was blindfolded, beaten and interrogated. The foreign soldiers asked him about the visitors who came to the house earlier that day, he said. He would be kept inside, blindfolded, for the duration of the raid.

The special forces operatives had also gone to the house next door, where a widower called Lal Mohammad lived with his six sons and three daughters. One of his sons, Mohammad Mohammad, who was 12 at the time, told the BBC that he and his brothers were brought outside and detained by the assault team. He was blindfolded and - possibly because of his young age - taken separately to Hussain's home and held there for the rest of the raid.

It was only after the troops left the village, hours later, that Abdul Aziz was able to take off his blindfold and go out into the morning light to the place where Hussain and Ruqqia and the boys had been sleeping. "There was blood everywhere", he said, "blood soaked into the sheets and the mattresses." According to members of both families who saw Hussain and Ruqqia's bodies, both had been shot in the head. Imran and Bilal's bloody bedclothes lay there, but the boys were gone.

BBC

BBCMohammad Mohammad ran back next door to his family home, where he had last seen his older brothers detained by the soldiers. He found Mohammad Wali, who was 26, and Mohammad Juma, who was 28, inside the home, dead with gunshot wounds to the head, he said. Other family members said that the two were shot at close range in the head, and an image of Mohammad Wali's body seen by the BBC appears to show a head wound.

Mohammad Mohammad's account appears to mirror the pattern of killings that had already raised suspicions among senior special forces officers.

"I swear to God, my brothers were farmers," he said. "They worked from dawn until night. They were neither with the Taliban nor with the government. They were killed for no reason."

According to the accounts of Abdul Aziz and other family members who saw Hussain and Ruqqia's bodies, their eyes were closed and their jaws had been bound shut with cloth tied under the jaw and around the head, maybe to allow the assault team to accurately photograph their faces - a standard procedure after a fatal shooting.

The young parents appeared to have been killed in their bed, the family said. It was not clear if they had woken up before they died. At first, the family assumed Imran and Bilal were dead too. But the boys had been airlifted out with the special forces, one-year-old Bilal with bullet wounds to his face and shoulder, three-year-old Imran with a gunshot wound in his abdomen, fighting for his young life.

BBC

BBC BBC

BBC BBC

BBCIn the aftermath of the raid, a British military commander had a decision to make. Under UK law, commanders are obliged to inform military police if there is any possibility that a Schedule 2 offence has been committed by a person under their command. Schedule 2 offences are serious offences like unlawful killing and grievous bodily harm. The guidance for commanding officers says that the circumstances must only "indicate to a reasonable person that a Schedule 2 offence may have been committed" in order to legally oblige them to refer the incident to the military police. It is considered a low bar.

In Shesh Aba, a woman was among the dead and two infant boys had been shot. An Afghan newswire report published the day of the raid quoted the local governor as saying that the foreign forces had "killed and wounded six civilians", including "two children". A former investigator from the Royal Military Police told the BBC that, based on the available information, there was "no question in my mind that this incident should have been referred to military police".

But the BBC has discovered that the raid was never referred to military police and never investigated by anyone outside of UK Special Forces. The Royal Military Police (RMP) told us that they did not appear to have been informed of the Shesh Aba raid at the time, and are now reviewing the incident "as a direct result" of our inquiries.

When asked by the BBC, the Ministry of Defence confirmed that British forces were involved in the raid and that a Serious Incident Review, or SIR (an internal review undertaken automatically after an operation goes wrong in a serious way) had been carried out, but that the commanding officer had decided against referring the incident to military police.

The MoD said: "There is a comprehensive MOD policy in place for actions to be taken in the event of possible civilian casualties.

"Following a review by senior Army lawyers, it was decided by the Commanding Officer, in accordance with the Armed Forces Act 2006 and MoD policy, that the circumstances did not require a referral to the Service Police."

Getty Images

Getty Images

The BBC asked both the MoD and RMP to reveal the rank of the commanding officer who made the decision, but both declined to say. The BBC has obtained a secret internal special forces document laying out the protocol for deciding on referrals to the military police. It appears to show that once an SIR has been completed, it has to go to the Director Special Forces - the highest-ranking special forces officer in the UK - for a decision on whether to refer the incident.

Director Special Forces at the time of the Shesh Aba raid was General Sir Mark Carleton-Smith, who went on to become the head of the British Army, before stepping down earlier this year. Asked by the BBC about the Shesha Aba raid, General Carleton-Smith said he could not recall whether he was briefed on the "specific tactical detail of the operation", but that he was in no doubt he would have been "guided by the advice of the in-theatre commanders", as well as the legal judgement of a senior Army lawyer that no referral to military police was necessary.

He said the recommendation to him at the time from the commanding officer in Afghanistan was that there was no evidence of a criminal offence, that the Rules of Engagement hadn't been broken, and that "the circumstances of the operation justified the lethal use of force". He added: "And I certainly never saw or read any evidence or advice that suggested unlawful behaviour".

General Carleton-Smith told the BBC it remains his view that "the Rules of Engagement were correctly observed despite the occasionally tragic outcomes that are sadly inevitable during war".

The Rules of Engagement that applied to this raid dictated that lethal force could only have been used against someone who posed an imminent threat to life. There has been no suggestion from the Ministry of Defence that any weapons were found at Hussain and Ruqqia's home or that they were armed when they were shot.

BBC

BBC

SIR reports were intended in part to help commanding officers make a decision about whether a referral to military police was necessary. But a former senior RMP officer who served at the time of the raid in Shesh Aba, who spoke to the BBC on condition of anonymity, said there were "serious problems" across the Armed Forces with the use of the reports.

"Instead of getting to the bottom of what happened and correcting any criminal behaviour, SIRs became a way of cleansing an incident of any wrongdoing," he said. "Some senior officers were using SIRs as a tool to prevent scrutiny. It seemed they were deciding on non-referral and then writing the SIR to justify the decision."

The problem was "widespread", the senior officer said, but UK Special Forces was "notable in its lack of referrals". The BBC has identified at least three other occasions when an SIR was completed by UK Special Forces but not referred to the RMP. "In Special Forces, it's easier to keep it 'in house'," the former senior officer said. "There's a lot less oversight."

A former RMP investigator who spoke to the BBC said he was "not surprised" that the Shesha Aba raid was not referred. "I'm afraid, given my experience of these kinds of cases, I'm not surprised that the commanding officer decided not to inform the police," he said. "But it's clear it should have been looked into."

A spokesperson for the RMP said that its current review, prompted by the BBC's inquiries, "should in no way be taken as implying that the incident was unlawful or that the British Armed Forces had improperly failed to make the Service Police aware, although these are factors that will be considered by our review team as a matter of course".

The MoD said that it was "the long-standing policy of successive governments not to comment on matters relating to Special Forces" and that all British military operations were "conducted in accordance with UK and international law, including the Law of Armed Conflict".

The BBC asked the MoD if anyone had ever been officially disciplined over the Shesh Aba raid, but they declined to respond.

BBC

BBCAs dawn broke over Nimruz that day, the helicopters that had brought the troops flew back to base bearing the wounded Imran and Bilal. The special forces had also taken Hussain's youngest brother, Rahmat Ullah, who was 12.

Rahmat had been detained during the raid and he had no idea what had happened. When his blindfold was finally removed, aboard the helicopter, he saw his young nephews. Imran was conscious, crying. "He looked like he was in severe pain," Rahmat recalled. "He asked me for water, but I didn't have any."

The boys were sent to separate military bases. The family was not allowed to go to where Imran was so, aged just three, he spent the first part of his recovery alone. Eventually he was transferred, and it fell to Abdul Aziz and their grandmother Mah Bibi to comfort the boys and try to explain that their parents were gone.

"They were just too small to understand," Abdul Aziz said. "Imran would cry more, maybe because of the pain, but maybe because he could sense that his mother was no longer alive."

BBC

BBC

Abdul Aziz was offered some compensation at the military hospital for the boys' injuries but he refused the money, he said. "I refused to benefit from the murderers at that time, they had destroyed our world," he said.

When the boys were discharged, their grandparents took them home to the village. They have lived there since, with their older sister Hajira, in the home where they were shot. They don't remember anything about that night, or the weeks that followed, but after they came home Imran began to scream in his sleep and sleepwalk outside during the night. "I don't know why I do it," he said. "I am asleep when it happens, and my grandfather or grandmother brings me home."

BBC

BBC

Imran is 13 now. He has a long surgical scar down the front of his torso and a scar on the left of his belly, and more scar tissue across his lower back. He has bullet fragments inside his torso - including a large fragment embedded in his spine. "Running causes me pain, and I feel pain in my stomach," he said, pointing gently to the scars on his belly and back. "I also feel more pain in the winter and when the summer comes I'm relieved."

Bilal is 11. He has a scar on his face from a bullet that hit him millimetres from his left eye and a scar on his shoulder where another round hit him and left a bullet fragment inside his bone. He gets pain in his arm when he uses it a lot, he said, and the position of the scar on his face is a permanent reminder of how close he came to death.

BBC

BBC

BBC

BBC

The boys go for a few hours in the mornings to a religious school, but there is no proper school nearby that they can attend for full time education. Imran enjoys the lessons, particularly reading. Bilal is less keen. "I don't like school," he said, with a smile. He likes playing with his older brother. On a cool afternoon in October, the two of them played marbles in the courtyard of their home, and they looked as though they were in their own little world. A few feet away, there was a Mulberry tree in the place where their parents were killed. Either side of the Mulberry tree were two thin Jujube trees, planted by Imran and Bilal, for Mohammad Wali and Mohammad Juma, their neighbours who were killed.

Imran and Bilal do not talk much about their parents. They have no memory of Hussain and Ruqqia, so their loss is defined by a general sense of absence. "I wish our mother and father were with us today," Imran said, "so we could go to the city to walk around and enjoy ourselves, as other children can."

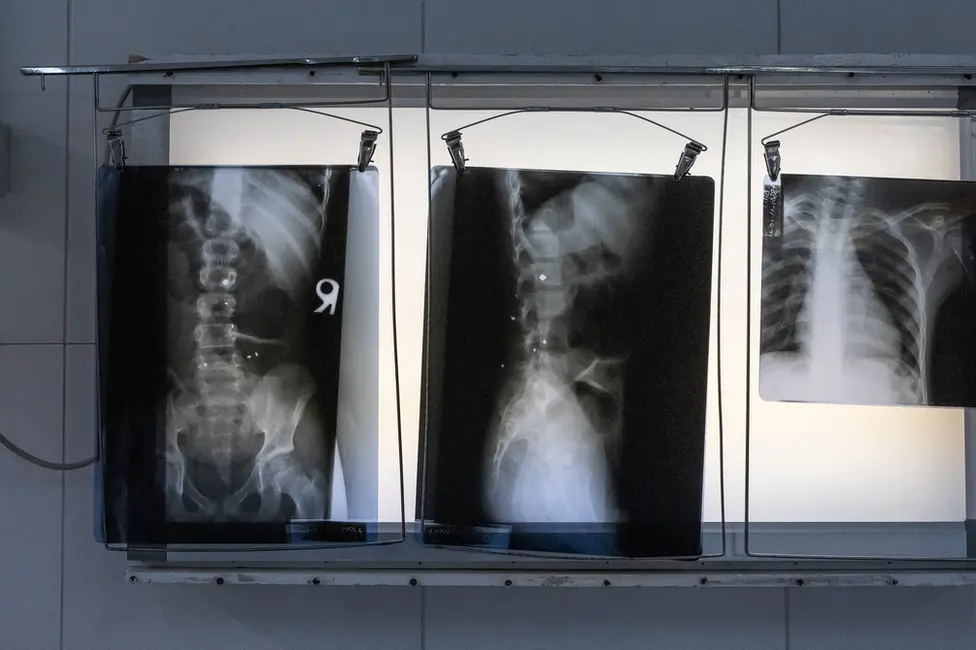

The family is poor, and the boys have had limited access to medical care since they were discharged a decade ago. Recently, they travelled to the trauma hospital in the city of Lashkar Gah, about six hours' drive from the village, for a medical examination arranged by the BBC. X-rays showed the bullet fragments still lodged in their bodies. It was the first time the boys had ever seen them. The doctors said that nothing could be done to safely remove the fragments from Imran's torso, so he will have to live with them. "He is lucky to be alive," the surgeon said.

As the boys were examined, Abdul Aziz sat quietly alongside them and held their hands, just as he had sat with them 10 years ago, in another hospital, when they were much smaller, knowing that they were his responsibility now.

BBC

BBC

BBC

BBC BBC

BBCHussain and Ruqqia were married on a hot summer's day in 2006, in Zahedan, Iran, where Ruqqia's family lived. Excitement had been building in the village in Afghanistan, and when the appointed day came Abdul Aziz and about 100 members of the wider family set out across the border for the ceremony.

When they returned a few days later with the new bride and groom, there were celebrations to rival the festival of Eid. Livestock was slaughtered to make rich meals for the family and their neighbours. Those who had new clothes wore them. Those who didn't have new clothes wore the best clothes they had. "It was a joyous moment for everyone," Abdul Aziz recalled. "From then on, I called Ruqqia my daughter."

Hussain opened a small grocery shop in the village. Ruqqia was a 'Hafiz Quran', a memoriser of the Muslim holy book, and she taught local children. Shortly after the wedding, their daughter Hajira was born, and then Imran, and a year and a half later Bilal. Hussain took on a new role as the head of the family and the financial provider. He doled out pocket money to his siblings, paid for their schooling and later their weddings. "He was our strength and power," said his younger brother, Mansour. "We didn't worry about a thing when he was alive."

BBC

BBC

When Hussain was killed, it forced Abdul Aziz back to work. Now, at 55, he spends his days digging irrigation canals for 200 Afghani - less than £2 - per day. He regrets turning down the offer of compensation for the boy's injuries. If it came again today he would accept. "I am getting older, and it is harder to work and harder to feed the children," he said.

At one time, Abdul Aziz would set off every day after work, under the burning sun or through bracing cold, to the cemetery where his son and daughter-in-law are buried. Hussain's mother, Mah Bibi, often walked with him. Eventually, her sadness overtook her and became a depression that she has not recovered from, and now she cannot go as often. Abdul Aziz suffers too. He is physically tired. But every Friday he walks a kilometre along the dusty track that leads from the village to the graves. They lie in a small, walled off area of the cemetery reserved for those killed by the foreign soldiers. There are eight graves there in total. Two belong to Hussain and Ruqqia. Two to Mohammad Wali and Mohammed Juma.

Last Friday, Abdul Aziz set out for his weekly visit. For half an hour, as the sun set, he sat still by the graves and said prayers for Hussain and for Ruqqia. He spoke to his son. "I told him that I missed him, and that I could still remember him when he was just a little boy," Abdul Aziz said afterwards. He had not uttered a word by the grave. "I do not speak to him aloud," he said. "I speak to him in my heart."

Kiyya Baloch and Ahmad Naveed Nazari contributed to this report

Do you have information about this story that you want to share?

Get in touch using SecureDrop, a highly anonymous and secure way of whistleblowing to the BBC which uses the TOR network.

Or by using the Signal messaging app, an end-to-end encrypted message service designed to protect your data.

- SecureDrop: http://kt2bqe753wj6dgarak2ryj4d6a5tccrivbvod5ab3uxhug5fi624vsqd.onion/

- Signal: 07714 956 936

Please note that the SecureDrop link will only work in a Tor browser. For information on keeping secure and anonymous, here's some advice on how to use SecureDrop.